Frances Watt

Scottish Artist Frances Watt is a woman of mystery in contemporary art. At the peak of her career in the 1960s, she achieved some measure of success as an artistic chronicler of the male-dominated world of money-making in London’s Square Mile financial district. By the early 1990s, Watts and her art were all but forgotten, casualties of the gender bias and short historical memory of her time. The recent sale of a cache of pieces, kept in storage for 30 years in Aberdeen, has drawn well-deserved attention back to an artist who made images both of trading stock brokers in bowlers--and of Christ turning water into wine.

Edith Frances Watt was born in 1923 in Falkirk, Scotland, the daughter of a Church of Scotland minister. When she was three, her father was called to the Scottish Kirk in Geneva, Switzerland, where she spent her childhood. The family returned to Scotland in 1936, and when Watt’s father died two years later, the aspiring artist and her mother moved to Highgate, London. She would live there unmarried for most of her life, devoting her time to drawing and the local choral society for which she designed programs.

Watts had formal art training at the Byam Shaw School of Drawing and Painting in London, honing her skills by copying the Great Masters. The Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection has one such sketch of Rembrandt’s oil painting, David and Jonathan. A second drawing of Christ's Entry into Jerusalem appears to be a study in classical architectural forms, where the figure of Jesus riding a donkey is dwarfed by the huge Roman triumphal arch through which he enters the city.

Watts's first public exhibition was in the 1950s. A decade later, she was commissioned by the Council of the Stock Exchange to create a visual record of business activities at The City. Working in pencil, pen, and watercolor she made hundreds of studies of anonymous financiers at desks and on the trading floors at the Royal Exchange, the London Discount Market, and Lloyds of London, many of them, used as illustrations in the Times newspaper.

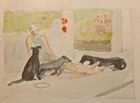

Watt's drawings on biblical themes present a very different side of this impersonal chronicler of the Square Mile. The Scottish parson's daughter revealed her true feelings about the world of high finance in an ink drawing, a pencil sketch and a watercolor in my collection, dating from 1979, based on Christ’s parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). A pair and trio of delightfully rendered dogs provide care and company for a begger at the gateway to a London park. Money moguls who have passed him by (one in a top hat!) can be glimpsed in the distance.

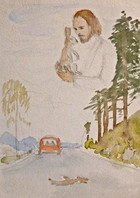

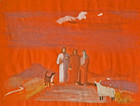

The artist's love for animals also found expression in a whimsical watercolor of Jesus tenderly taking a roadkill rabbit into his arms and in a more traditional study of the Good Shepherd. A dog and a sheep figure as two more traveling companions for the Risen Christ and two disciples in a mixed media painting of the Road to Emmaus story in Luke 24:13-32. Watt wrote on the margin of the painting: Joy of companionship...The earth is subject to Him...The animals recognize Him...The GREAT PEACE has come into the World...Atmosphere-Peace.

Another post-Resurrection appearance of Christ is the subject of two other drawings on display. Watt depicts the scene described in John 22:18-23, when Christ has just predicted Peter's death by martyrdom. The apostle, then, asks the Lord what destiny awaits "the disciple whom Jesus loves," believed to be John the Evangelist. Watt was particularly interested in clothing her figures in the right biblical dress and gives John a different outfit in each variation--a three-quarter robe and a short tunic with pants.

Christ’s first miracle of turning water into wine is the subject of two more drawings in the collection. In a larger sketch with notations, Watt wrote out a prose poem on the theme of Christ’s care, displayed at the Wedding in Cana. In turning water into wine, she notes, Christ wanted us “not just to have something to drink, but that it should be something to make us glad.” We know little about this reclusive artist, but even in her solitude, Watt found cause for joy. The final refrain of the poem reads: “Christ comes to us in our festivities, not just in our sorrows, trials and illness. He doesn’t want our happiness spoilt--Christ’s care.”

Lenten Carols Program

Cross on the Green (verso)

David and Jonathan (After Rembrandt)

Entry into Jerusalem

Lazarus and the Dogs I

Lazarus and the Dogs II

Lazarus and the Dogs III

Jesus and the Rabbit

The Good Shepherd

The Good Samaritan

The Road to Emmaus

"Lord, What Will This Man Do?"

"Lord What Will This Man Do?" II

Turning Water into Wine

Turning Water into Wine (with notations)

Turning Water into Wine (detail)

Turning Water into Wine (detail)

The Journey of the Magi