James Quentin Young

(1936-2022)

American Artist James Quentin Young was the quintessential modern maker of crosses. Long before the current trend for “found object” art, Young was rearranging L-shaped parts from an old electric motor one day in 1973, when he saw a cross taking shape from the pieces similar to those on the altars of cathedral side chapels. It was the first of many crosses Young made from discarded things over the next nearly five decades. In fact, cross imagery became the defining motif of his art. Working most of the time in two small rooms in the basement of an antique shop, the Minnesota assemblage artist created dozens of new crosses each year with an inventory of hundreds of pieces.

Young hoped his contemporary “found object” cross images would help recover the true meaning of this defining sign of Christianity for a secular culture where the Cross has all too often been used and abused both as gaudy costume jewelry and a flaming symbol of racial superiority. He thought the exploitation of this sacred image for commercial and ideological ends obscured its true importance as the supreme emblem of divine love and redemption. “I believe I have been called to a ministry,” he once explained. “The crosses I make are a witness to my Christian faith. I want to provoke thoughtful meditation on the meaning and symbolism of the Cross.”

Religious imagery long figured in Young’s art. He carved a wood crucifixion scene, while studying art education at Macalaster College in St. Paul, Minnesota, in the late 1950s. Sacred themes also featured in his graduate work in painting at the University of the Americas in Mexico City in the early 1960s, where he was profoundly affected by the road side shrines and the fervent penitential devotion of Mexican Roman Catholics. During over thirty years teaching art in Minnesota public schools, Young continued to make religious-themed works in his free time, but it was only after he retired in 1994 that he realized his vocation as an artist of the Cross.

In searching for the raw material for his assemblage works, Young became a familiar face at flea markets and garage sales in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. Family, friends, and neighbors also contributed to the store of found objects filling up his studio. Scorched and rusting bits of metal, broken tail lights, old tool and furniture parts, pebbles and driftwood, paint can lids and synthetic pearls all found their way into his sculptural compositions. Young picked up some of his most usable bits and bobs on railroad tracks and streets, where they have been shaped and polished by passing trains and vehicles.

The assemblage artist saw a sound theological underpinning for using what our culture considers trash in his pieces. As the Apostle Paul writes in 2 Corinthians 5:17 (KJV), “In Christ…old things are passed away, behold, all things are become new.” Young considered his works to be illustrations of this transformation Christ offers us. He believed that in the same way the artist rescues unwanted, damaged, and discarded objects from waste bins and city dumps and recreates them as art, Christ can reclaim, restore, and bring new life to the rejected, wounded, and marginalized in human society.

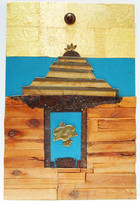

In their simplest variations, cruciform shapes function in Young's assemblage pieces as load-bearers, support to a gilded triangle with a counterbalancing shadow in Stability, his largest work in the Collection. A rusted and flaking doubled cross in his contrasting image of Perplexity seems to be crumbling under the weight of a ziggurat of layered wood. Young embodied his fascination with roadside shrines in Black Forest Cross, beautifully composed of autumnal-tinted strips of wood and a recycled crucifix and pointed to the importance of holy writ in faith communities in Scroll Cross where a cruciform in wood and metal is supported by red signal lights resembling the ends of rolled manuscripts.

Using evocative titles and carefully chosen materials, Young helped to deepen our understanding of the Passion narratives in other crosses and crucifixes on display here. In Forgotten Not a touch of gilding at the upper edge of this rough-textured cross panel of weathered wood and stone suggests the coming Resurrection. Tar-flecked wood and a pitch-black shingle provide a somber background for a rusted metal cut-out of a human form on a white cross in Noon Darkness, while copper pieces of variegated color add a mellow richness to Sunset at Golgotha II, suggesting the redeeming death of Christ has truly been accomplished.

The most minimal cross image in my collection is Young’s weathered wood on wood cross, From His Side, where added bits of red-toned metal evoke Christ’s bleeding lance wound. In expressively understanded assemblage pieces of this kind, the Minnesota artist of faith reminded us the real Cross was far removed from the elaborate symbols in gold and silver used down the centuries in church rituals. Since the Crucifixion at Golgotha took place in the ancient equivalent of the town dump, Young suspected the Roman rulers might very well have used pieces of discarded wood to cobble together the cross bar and post on which Christ died.