Stuart Duffin

Scottish Artist Stuart Duffin is a masterful modern symbol maker. A typical work by Duffin might bring together in detailed composition images of an antique map, a feral cat skull, an Italian travel photo, a desiccated fish, a cracked egg, a bird in a bell jar, a Victorian music box, and crockery broken by boisterous family cats. The artist describes his art-making as “a conscious form of dreaming,” where seemingly disparate objects regroup in new relationships that invite our interpretation. “It’s personal symbolism,” he says, “but not so personal the viewer cannot enter into it.”

Born in 1959, Duffin is Master Etcher at the Glasgow Print Studio, a three level shop, gallery, and studio complex near the city’s landmark Trongate, where graphic artists in various media can come together to work. He also has his own etching studio with a copperplate press at his home in South Aberdeenshire. Duffin creates visually complex digital prints, in addition to etchings, but is best known for his meticulous mezzotints, a printing technique where thousands of ink-holding dots and burrs are hand-pressed into the print plate to create rich tonal effects. Duffin also paints canvases of arranged objects with trompe l’oeil realism, joking that he is “incapable of using a brush more than a quarter of an inch across.”

One large scale sacred art piece in Duffin’s mix and match style of symbolism hangs in Glasgow’s Langside Parish Church of Scotland, a 360 cm. long oil painting of the Last Supper, replacing a similar work by him that was destroyed in a 2009 fire. The artist, family members, and friends stand in for Christ’s disciples in this Leonardo da Vinci styled tableau. The bitter herb, dandelion, and the thorn-feeding goldfinch on view are time-honored symbols of the Passion, but Duffin also includes his daughter’s wedding bouquet and sets Christ before a bullet-scarred window with a view of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount.

The artist believes his love for meaningful detail comes out of a childhood fascination with Victorian-era museum displays, where all kinds of objects of scientific interest could be seen classified, labelled, and neatly arranged in glass cases. Had Duffin not gone to art school, he would have become a scientist, so, it should come as no surprise to find he has organized his own body of work into titled, dated, programmatic periods: Boys on Film (1982-1984); Nostalgia (1985-1991); The Colour of Ashes (1992-1995); Dreaming of Jerusalem (1996-1999); Sacred Science (2000-2005); Reason or Revelation (2006 onwards)

Two etchings in the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection from the Nostalgia period—The Quieter Side of Life and Laughter and Forgetting—include a recurring image of the Virgin Mary, inspired by the medieval Madonnas of Duccio and Simone Martini, which Duffin studied on visits in the 1980s to Italy. The titles come from the bittersweet lyrics of David Sylvian, onetime lead vocalist for Japan, a popular British new wave pop band of the 1970s. Images of historic permanence—medieval Italian cathedrals—are imprinted on broken cups. Child-like puppets wear liturgical vestments. For Duffin, “nostalgia” in this period suggested both “a return home” and “pain.”

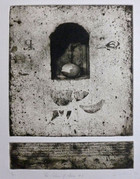

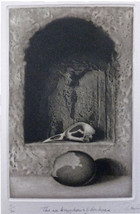

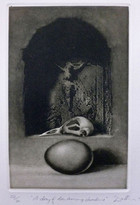

Duffin travelled to Russia in 1992 to take part in a print workshop outside of Moscow and experienced firsthand the collapse of Communism. This world-changing event defined his Colour of Ashes period and was associated for him with images of smoke, crows, barren trees, and animal skulls in melting snow. Duffin was working on a study of three trees on a hill with a feral cat skull in the foreground, when he remembered it was Good Friday. This recollection inspired a graphic series, combining photos of an Italian roadside shrine of the Crucifixion with images of bird skulls and eggs, whole and cracked. Four prints with these Passion motifs are on view in the image gallery.

Four years later, the artist was invited to Jerusalem in a Glasgow Print Studio international exchange program. This 1996 visit to the Holy Land proved to be turning point in Duffin's art-making, inspiring richly symbolic works of more explicit meaning. As he explains: “Although Jerusalem is the closest we can get to heaven of our own accord, nowhere more than in the Holy City did I experience the loss of paradise or our separation from God/the divine/our humanity in a more painfully obvious way.” For him, the welfare of the troubled city, sacred to three faiths, has come to serve as “a barometer to our own spiritual welfare not only as individuals but of society as a whole.”

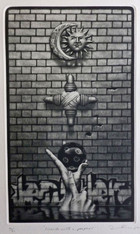

Duffin has made close to a hundred etchings, mezzotints, digital prints, and paintings with repeating Middle Eastern motifs--three of them in the image gallery. Brick and concrete walls (protecting and confining) are a frequent backdrop, often riddled with bullet holes. They are often covered in ideologically-loaded messages like GOD, ZION, or simply WHY, recalling the graffiti scrawled on Jerusalem walls since the Intifada Palestinian riots of the late 1980s. Objects associated with the Holy City's three contending monotheistic faiths hang from the background walls or rest on altar-platforms. In this world where all talk and no one hears, hand-signers often form one of the seven letters in the Hebrew word for "Jerusalem."

Duffin's own message could not be clearer in the oil painting in my collection, Blue Madonna. An Islamic crescent, a Star of David and a Cross combine with faded letters on a wall to spell out the word: COEXIST. The Cross dangles from a chain draped over an icon of Duffin's Italianate Madonna. She is placed above a typical Jerusalem ceramic street marker in Hebrew, Arabic, and English--evidence of coexistence in practice. The Christian image is halfway between a scorched antique print of the Holy City with Hebrew lettering, and a glass sphere filled with blue water symbolizing the earth. Could it also be an apothecary globe representing Muslim medical arts? I suggested this to Duffin,and he willingly accepted my unintended reading. Such is the way of symbols.