Konstantin Kalynovych

Lovers of the masterworks of North European art will experience déjà vu seeing the surrealistic images of Russian-Ukrainian Artist Konstantin Kalynovych. In one book plate, the 13-year old Albrecht Durer in a famous self-portrait points through shattered ice at an equally famous Durer image of a stag beetle. In another small format print, Pieter Bruegel the Elder (in self-portrait) pulls the string on a bird trap, copied from the artist’s winter landscapes. A bird flutters freely into Rembrandt’s room in a Kalynovych variation of the Dutch master’s Self Portrait Etching at the Window. Even the iconic image of the artist at his easel from Johannes Vermeer’s The Allegory of Painting reappears in a bleak winter landscape.

Kalynovych describes these richly detailed pastiche pieces as “winter dreams,” where the meanings are “murky, like a dream on a foggy winter night.” It is the rare viewer today who can read signs and symbols like the contemporaries of the Great European Masters, but Kalynovych invites us to revisit this lost visual world and try to interpret his Postmodern variations on past motifs. The artist’s credo is summed up in a Bible verse, quoted in a 2007 album of his work: “That thing that has been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done, is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.” (Ecclesiastes 1:9, KJV)

Born in the Siberian city of Novokuznetsk in 1959, Kalynovych now lives in Kyiv. He once attended a state school for artistically-gifted children. His love for the great works of Western art was nurtured on visits to the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad (now, St. Petersburg), when he was studying architecture at the city’s historic Engineering Construction Institute. Kalynovych eventually discovered his true talent for etching at a Leningrad graphic arts studio and honed these skills at what is now the Ukrainian Academy of Printing in Lviv, excelling at book plate design and book illustration.

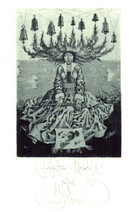

In hand-made editions of The Song of Songs, Revelation of St. John and a print series on Ecclesiastes, Kalynovych developed his own enigmatic iconography out of traditional religious symbols. One curious example is the book plate print, Remembrance of Noah’s Ark, in the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection. A woman resembling a seer from the Ecclesiastes cycle appears in the throes of divine inspiration. She stands before a stone wall where a dead bird lies on a fringed cloth, perhaps, one sent out from the ark in search of dry land. The wreck of Noah’s boat lies atop a snow-covered mountain peak in the background. Land-locked ships are a recurrent theme in Kalynovych prints. Your interpretation is a good as mine.

Wanderers figure prominently in Kalynovych’s works, moving beyond familiar boundaries into unknown terrain on mysterious metaphysical quests. Birds are ever-present companions of the human experience, creatures who move between heaven and earth, indifferent, if not downright hostile, to human desires and designs. They cast an ominous Shadow of Destiny over one firewood-laden peasant and his dog in a print, drawn straight out of a Brueghel winter scene. You might well ask who is the hunter and the hunted in Hunting the Big Owl, where a sturdy Netherlandish figure with gun in hand, strides confidently into the woods, unaware of an alarmingly large owl, poised to swoop down from a separate star-lit realm.

Angels are omnipresent, as well, in the artist’s visual universe. As celestial beings, they easily cross the great divide between the natural and supernatural, acting as agents of both judgment and mercy. Angels appear as majestic emissaries of the Apocalypse in The Second Angel and The Second Trumpet and as guardians of the seasons in Angel of Winter and Angel of Summer, looking on with lantern in hand as flocks of birds burst from a gargantuan shell to mark The Beginning of Spring. They even keep roadside campfires burning for the beasts of the fields and for lost wayfarers.

The artist is particularly drawn to the foundational story of the Judeo-Christian tradition: the Fall of Humanity in the Garden of Eden. Eve offers Adam the forbidden fruit in the Rembrandt etching within in an etching in Kalynovych’s aforementioned depiction of the Dutch Master at his window. German Renaissance Painter Lucas Cranach’s vision of Paradise (complete with a nesting bird atop a winsome lion) is the inspiration for a Kalynovych print where the First Couple sit under the apple tree, watching a falling star. A Flemish brocade serves as backdrop for a third image of Eden as a serpent-eaten apple, where Adam and Eve blissfully ignore a finger-wagging God the Father.

In Adam's Dream, a voluptuous Eve stretches out on an intricately patterned flying carpet beside two of Kalynovych's favorite symbols--an overturned chalice and a bitten apple. The chalice hints at the Holy Grail, the object of mythic quest, glimpsed as the shimmering and unattainable vision of the lady-on-the-lake in The Last Snow. More often, the sacred wine is spilled out in Kalynovych's world of visual paradox, just as the alluring apple of the Garden of Eden lies half-eaten in the snow before a sleeping figure with Daliesque moustache in Winter Dream No. 5. Bread crumbs join the apple core and spilled chalice as remnants of a quasi-Eucharistic picnic in the surrealistic image, Forgotten Melodies II.

If Kalynovych has a special affinity with any of the Great North European Masters it must surely be with Hieronymus Bosch. The artist pays homage to the early Netherlandish Renaissance painter in Hieronymus' Tree, where a close-up of the suffering Jesus from Bosch's painting, Christ Carrying the Cross (c. 1490) appears to the right of a barren bush strung with visual vignettes from other Bosch canvases: The letter-carrying bird man in funnel hat from the left panel of the The Temptation of St. Anthony triptych(c. 1501), the black bird on a spherical nest from from St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness (c. 1498), a variation of the wide-eyed owl in the central panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510), and two faces in the crowd from his paintings of Christ's Passion.

In the aptly titled print, The Great Mystificator, Kalynovych turns the peddler from Bosch's panting of The Wayfarer (1510) into an image of the artist as master illusionist, carrying a wicker basket of visual tricks. The peaked hat held out by the traveler in the Bosch canvas is transformed in Kalynovych's graphic variation into a cornucopia containing a white hole in the universe, a portal to Paradise open to the saints and their angelic guides. This beatific vision comes straight out of The Ascent of the Blessed panel from Bosch's oil on wood polyptych, Visions of the Hereafter (1490-1515.) With sleight of hand, the artist has become a mediator of salvation.

The Point of St. Johannes

400 Years by the Window

Vermeer in the Snow

David and Goliath

Rembrance of Noah’s Ark

Hope

Shadow of Destiny

Hunting the Big Owl II

The Second Angel

The Second Trumpet

Angel of Winter

Angel of Summer

Beginning of Spring III

Angel by the Fire

Garden of Eden

Apple of Temptation

Adam’s Dream

The Last Snow

Winter Dream No. 5

Forgotten Melody II

Hieronymus’ Tree