Michel Ciry

Michel Ciry (1919-2018)

Michel Ciry was singular figure in modern French culture. He was the composer of six symphonies for orchestra, mixed choir, and soloist. He published 36 volumes of memoirs. He was a master of the modern etching, who designed postage stamps and illustrated literary classics by authors ranging from Emily Bronte to Franz Kafka. And if all these accomplishments were not enough, he painted portraits and landscapes of luminous simplicity.

The extraordinary range of Ciry's talent was not the only thing that sets him apart from his West European contemporaries. He was a committed Christian whose art was largely devoted to sacred themes. He also chose to remain celibate, living in self-imposed exile from the Paris art scene for over fifty years on the seacoast of Normandy in Varengeville-sur-Mer, where a museum opened in 2012 to display works in his personal collection from a career spanning over seven decades.

Born in 1919 in La Baule in South Brittany, Ciry showed promise as both an artist and musician while he was still a teenager. He created his first etching when he was sixteen and made his public debut three years later at an exhibition at the Petit Palais in Paris. A student of contemporary French musician, Nadia Boulanger, he pursued a parallel career in music, creating orchestral works on sacred themes like Pieta and Mystere de Jesus before giving up composing in 1958 to devote himself to painting.

Writing remained a constant in Ciry’s life from the moment he began keeping a journal in 1942. First published in 1971, his memoirs, recorded by dated entries, are both the confessions of an artist struggling with his craft and the oft acerbic musings of a chronicler of modern times who made no secret of the fact he would rather have lived in the 17th century than in an age of decline “when the lie is sacred and counterfeiting is legalized.”

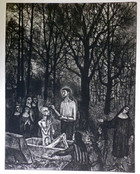

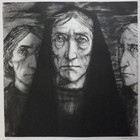

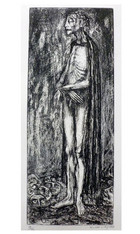

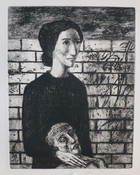

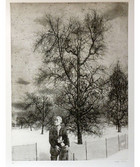

Ciry has been described as an artist of solitude. His figures seem to be lone actors on a stage empty of all but essential props. Our eyes are drawn to ordinary faces and hands, transformed by light and shadow, as seen in numerous images of Stabat Mater, depicting the Virgin Mary at the foot of the Cross. When landscapes appear, they are places of special purpose. Ciry uses the barren winter woods and orchards of Varengeville-sur-Mer as backdrops in depictions of the Visitation and the Raising of Lazarus, bringing to mind the dark forest of mid-life where Dante’s hero finds himself in the opening stanza of The Divine Comedy.

Ciry’s sacred subjects stare out at us like icon images. Sometimes, he catches them unawares in profile in moments of contemplation. Their attention is usually fixed on Christ, a presence sensed just beyond the visual plane, whether it is Mary of Bethany seated at his feet or Mary Magdalene at the foot of the Cross. Ciry frequently focuses on the faces of the two disciples who met Christ on the road to Emmaus lost in doubt and wonder at what has just been revealed to them in the breaking of the evening bread.

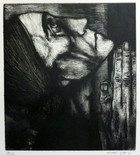

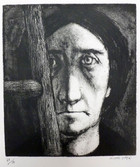

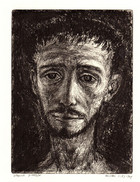

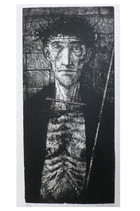

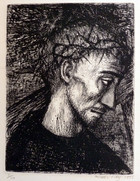

The Christ we encounter in this rich body of sacred art is not the haloed, heavenly-minded Savior typical of much Western religious imagery. Ciry’s Jesus is a vulnerable, close-cropped, sunken-cheeked figure with three day’s growth of beard and unspeakably sad eyes. As French Roman Catholic Writer Francois Mauriac once observed: “Ciry knows how to make divinity shine through a poor face similar to those we walk past on the street.” Cut this Christ and you know he bleeds like the rest of us.

The Passion of Christ looms large in the narrative art of Ciry—the subject of 25 pieces in the Collection. We see Jesus mocked in two versions from 1950 and 1962; Christ laboring under the Cross in variations from 1956 and 1962; and two depictions of Pieta from 1950 and 1954. There are gruesome still-lifes in print and on canvas of the instruments of his Passion, still dripping blood, and a horrifying (anatomically accurate) close-up of Christ's nail-pierced wrist. “It seems my lot has been to translate the anguish, the pain, the diversity of torments that can assail a human being,” explained Ciry. “I do not cultivate this sadness but it imposes itself in such a way there is hardly space for anything else in my work but this.”

When a friend once urged Ciry to renounce images of solitude and become “a painter of love,” the artist was quick to defend himself. “How could I be anything else but a painter of love?” he wrote. “It is precisely my great and slightly mad ambition in this time of hatred to want to stay on the side of love.”

One of Ciry’s favorite subjects was the Return of the Prodigal Son. He depicted the meeting of the loving father and wayward child from Christ’s parable in numerous variations. In two etchings in the Collection, we see the embracing pair from afar in a typical winter landscape and the serene face of the son in tight close-up, clutching his father’s vest. “I consider this theme to be one of the most beautiful there is,” explained Ciry. “It is all love. What, indeed, can be more beautiful?”

Un train d’enfer (cover)

The Solitude of Jesus

The Samaritan Woman

Stabet Mater

Stabat Mater I

Stabat Mater II

Stabat Mater IX

The Visitation (1978)

The Raising of Lazarus

The Holy Women

The Better Part

Mary Magdalene

Emmaus

Emmaus

Jesus

The Prayer

Christ of Sorrows (1950)

Ecce Homo (1962)

Carrying the Cross (1956)

Pieta of Notre Dame (1950)

Pieta (1954)

Crucifixion

Passion

Passion

Return of the Prodigal Son no. 2