Robert O. Hodgell

(1922-2000)

American Artist Robert O. Hodgell was your typical “preacher’s kid.” The son of a Methodist minister, he heard enough sermons growing up in Kansas to view the institutional church as an adult with a jaundiced eye. Yet, the foundational stories of his childhood faith intrigued and challenged him throughout his sixty-year career as a painter, printmaker, sculptor and illustrator, resulting in a body of work unique in American sacred art—by turns, alienating, anguished, poignant, and prophetic in a compellingly modern way.

The teen-aged Hodgell was more keen on track and field than art-making, but that all changed in 1939, when he had a chance to watch the renowned Regionalist Artist, John Steuart Curry, working on murals at the Kansas State Capitol in Topeka. Curry took him on as an apprentice-assistant, and Hodgell progressed from cleaning brushes to putting some of the finishing touches on the huge historical landscapes. Hodgell worked with Curry the last six years of the artist’s life and spoke of him as “the biggest influence in my life.”

After serving in the Pacific in World War II, Hodgell finished his art studies at the University of Wisconsin, painted murals for the 1948 Wisconsin Centennial Exhibition, took a variety of teaching jobs, travelled around Mexico, and provided illustrations for children’s books, Our Wonderful World Encyclopedia, and Playboy. He was a contributor to motive, the Methodist Student Movement magazine published from 1941 to 1972, noted for its progressive editorials and innovative art. In 1962, Hodgell joined the new art department at Florida Presbyterian College (now, Eckerd College) with the proviso that he keep his beard and his connection to Playboy. He gave up teaching in 1977 to devote himself fulltime to art-making.

Hodgell kept a reproduction in his Sarasota, Florida, studio of the beardless Head of Christ he created in 1950 for motive. It was framed with what he wryly called his “first fan letter” from a woman church-goer offended by this unorthodox depiction of Jesus. Hodgell was determined to replace prettified “bearded lady” Christs with a younger, stronger image you could recognize without resorting to what he termed "the standard camouflage/symbolism." Motive Editor B.J. Stiles believed the artist's depictions of Jesus offered a “fresh vision” to people of faith “reared in the comforting confines of [Warner] Sallman’s Head of Christ and countless bad reproductions of Durer and Rembrandt.”

Few sacred cows escaped Hodgell’s satiric lasso in his large format linocuts on biblical themes. He took aim at Fundamentalist Protestant beliefs in a literal seven-day Creation of the World in Eden Revised where Adam and Eve (borrowed from a Durer engraving) accept the fated apple from a dinosaur in a Garden of Eden made over as Jurassic Park. Hodgell created a very different mood in Adam Had it All, showing the first couple after the Fall locked in an anguished erotic embrace as the fruit of the forbidden tree floats out of their grasp. A passing butterfly hints all may not be lost.

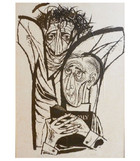

Hodgell raised eyebrows with his depiction of a seedy Prodigal Son settled down among the swine with a liquor bottle protruding from his pocket and a Playboy Bunny cufflink displayed on his sleeve--a cheeky take on sacred text recalling his linocut of Daniel Among the Lions, where the Old Testament hero sits among flies and dung, regally ignored by two less than ravenous beasts. In contrast, Hodgell’s companion print, The Prodigal’s Return, is a poignant, expressionistic image of paternal love where the repentant son is all but smothered in his father’s encompassing embrace.

The artist’s most savage visual critiques were reserved for institutionalized Christianity and its comfortable, status-quo-affirming faith. In But Lead Us Not Into Unpleasantness, Hodgell presents a church where the image of Christ on the Cross is concealed by a sheet and floral display so as not to disturb Sunday worshippers. A self-satisfied cleric clutching the Bible claims to be The Spokesman for the gagged and crucified Christ in a second satirical linocut, while in The Confrontation, a clergyman wraps himself in horror in his holy cloak, when a disheveled Jesus from the streets extends a nail-pierced hand.

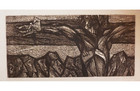

Hodgell’s edgy style of artmaking was on full expressive display in a cycle of prints he made on the Passion of Christ. The images were inspired by drawings the artist had made to illustrate a talk he gave one Easter season at the Des Moines Art Center. They had stayed with Hodgell for ten years, before he let them loose in this linocut series, which he called "a portrait of an EVENT." As Hodgell explained in the November 1959 edition of motive: “Faces, hands, drapes, attitudes are not treated as people or things or places but as visual experiences which can arouse or convey meanings directly."

The viewer cannot help but respond in a visceral way. In the linocut, Way of the Cross--whose large size evokes the artist’s mural paintings--the ground line tilts disturbingly upward under the weight of a crowd scratched out in violent lines, while a bent and bound Christ in profile labors into the void of Golgotha. In Behold the Man, our eyes fix on the nail-torn hand and twisted torso of Christ hanging on a huge cross beam above a grotesque, jagged-edged frieze of faces. Not a bearded-lady in sight!