Barry Moser

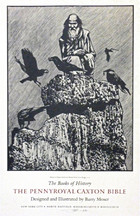

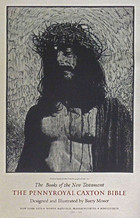

American Printmaker Barry Moser reckons that there are probably no more than 500 skilled wood engravers in the world today. He is certainly one of the best contemporary practitioners of this laboriously detailed art form, having created wood engravings to illustrate enough classic works of literature to start his own Great Books library. Moser is also an accomplished book designer and printer. Altogether he has illustrated and laid-out over 300 titles, including The Odyssey, Moby Dick, The Scarlet Letter, Frankenstein, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—to name just a few.

One Goliath of World Culture was long beyond the means of Moser’s David-sized Pennyroyal Press. He had been taking part in a panel discussion back in the 1970s, when someone in the audience asked what book would be at the top of his project wish-list. Moser answered without hesitation: “The Bible.” It would only be on the eve of the new millennium that he was able to realize his dream of creating the only Bible designed and illustrated by a single artist in the 20th century—a modern contribution to a sacred book-making tradition dating back 550 years to Gutenberg’s first printed Bible.

In Moser’s autobiographical essay, "A Bookwright’s Tale," he claims the closest he came to great literature in the male-dominated world he knew as a boy in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where he was born in 1940, were the Classics Illustrated comics he read to pass English tests at the military academy he attended. Art was not considered “a manly endeavor,” so, he took up “industrial design." After completing his studies at Auburn University and the University of Chattanooga, Moser quite naturally settled into a job teaching mechanical drawing at a Southern all-boys school.

Moser “found religion” on the revival meeting circuit during his college years. After surviving a freak shooting accident, he felt the call of the Lord to become a licensed Methodist preacher. His study of the King James Bible finally opened his eyes to the joys of book-learning, but life among conservative Protestants turned him into a self-described “reprobate.” One reason Moser was so determined to print his own edition of the Holy Scriptures was “to reclaim the Bible for myself and purge it of the intolerant and ignorant readings that so many of my fellow religionists imbued it with.”

Moser’s horizons expanded in 1967, when he accepted a teaching position at a private school in Massachusetts and had the opportunity to study with Graphic Artist Leonard Baskin. His visit to Baskin’s Gehenna Press print shop in November 1968 proved a turning point in his life. Taking in the noise of the presses, the smell of ink, and the feel of handmade paper, Moser says he “stepped into the world of the rest of my life.” He convinced the headmaster of his school to set up a print shop in an old railway station, opening the way for the founding of his own Pennyroyal Press in 1970.

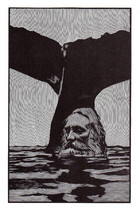

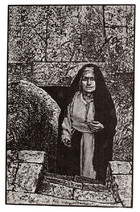

A quarter-century (and many book titles) later, Moser finally decided he was “old and experienced enough” to take on the long-postponed Bible project and found himself a sponsor. His mission was “to avoid the obvious and expected.” Traditional biblical tableaux like Noah’s ark of animals or the Christmas manger scene are missing. You will find, instead, unusual (often explicit) images like Jephthah’s daughter sacrificed or King Saul’s body nailed to a wall. Altered perspectives invite new insights. We encounter Jonah and the whale in the sea at eye level and view a stunned Mary Magdalene at the empty tomb on Easter morning through the eyes of the Risen Christ.

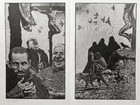

Moser labored four and a half years to create more than 320 wood engravings for his Pennyroyal Caxton edition of the Bible and began with the subject he considered the most difficult: The Crucifixion. He was not satisfied with his first version. He needed to get “down at the level where blood and dirt and feral dogs mingle.” The final image, spread over two panels, focuses on the mockers at Golgotha, laughing at each other’s jokes, sharing a quick lunch, teasing the gathering crows, indifferent to those grieving for the dying Christ. Says Moser: “To tell the story, to confess the truth, the image had to be painful to look at, strident, discordant, and rude.”

The majority of Moser's illustrations are portraits. His figures from the Bible are almost always alone, the state Moser believes “where we all meet and wrestle with God or the idea of God.” Abraham, Moses, Ruth, and Esther are all there, but even Moser’s former Bible-pounding Fundamentalist friends would need a good concordance to identify some of them. There is Puah, the midwife who refused to kill the Hebrew babies (Exodus 1: 15-17); Achsah, the daughter of Caleb who wanted more land with springs (Judges 1:14-15), and Huram, the artisan who worked on King Solomon’s Temple (I Kings 7:40).

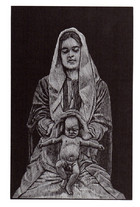

This is a gallery of lived-in faces; many of them, drawn from life. The charms of Delilah are a bit shop-worn. The Virgin Mary is a mother like any other. Moser's Christ is not the blue-eyed pretty boy of traditional religious art but modeled on the swarthy features of a local chef. “If there is a theme to my illustrations for the Bible it is simply the human condition,” says Moser. “My characters are not pious-looking. They smell of fish and sweat, not sanctity and saintliness. They wear the livery of human imperfection. They are real people.”

Studying Moser’s thoughtful choice of images for the Pennyroyal Caxton Bible, you may well wonder if the artist protests too much about his loss of faith. As the editors of the sacred arts journal, IMAGE, have observed of Moser: “He’s the most honest-to-God God-haunted soul we’ve seen in a long time. His illustrations of the Bible always humanize what is often etherealized; in that sense, they are more profoundly incarnational than the work of the religiously gung-ho.”

Resources: Barry Moser, "A Bookwright’s Tale", Image, Issue 71.