Brian Whelan

All that glitters is not gold leaf in the sacred art of Brian Whelan. The gleam in the Irish Artist’s haloes and Holy Grails actually comes from foil candy wrappers. This whimsical mix of the sacred and the mundane --the cosmic and the comic--appeals to post-moderns who prefer their religion packaged in a bit of irony. It can hardly be called trendy. Whelan’s style is as old as the medieval artisans who carved gargoyles next to saints and illuminated sacred texts with scandalous marginalia. Seeing a Whelan painting, writes one art critic, is like “looking at a stained glass window through the eyes of Bart Simpson.”

Whelan may pose as medieval jester, but no less a sacred art critic than Sister Wendy Beckett sees his idiosyncratic creations as “clear, strong, prayerful work with joy at its center.” Consider The Dream of the Three Kings in the collection, based on a famous Romanesque stone-carving in the Autun Cathedral in France. You cannot help but smile at the hairy legs and wiggling toes of the sleeping Magi, protruding from a blanket too small to cover them, but what brilliant colors the stain-glass patterned quilt displays, reflecting the glory of the heavenly hosts who have come to lead the Wise Men home!

The artist clearly enjoys turning tradition on its head in his Last Supper by showing us the back of Christ. This bit of brazenness in the collection draws our attention to the disciples. For those of us who have long wondered just who is who in the usually anonymous line-up at the table, Whelan helpfully depicts each of the twelve with an identifying symbol. Peter has his keys. Bartholomew holds a flaying knife as the patron saint of tanners. Thomas has a T-square as patron of architects. Matthew, the tax-collector, grasps a money bag—not Judas, as you might expect. The betrayer of Christ has had the bad luck to upset the salt cellar!

Whelan’s art is centered on story-telling. Born in London in 1957 to Irish parents, his sense of ethnicity in the diaspora was largely shaped by collective memories passed on in oral form--preferably over a pint at the pub--with an embellishment or two. Whelan is the rare artist-raconteur who enjoys talking about his art almost as much as making it. His e-mail correspondence with Southern California Lutheran Minister Jeff Frohner, collected in The Exchange, offers a clever, worldly-wise discussion of what sacred art-making might be all about, as they tease out new meanings from the artist’s paintings.

After studying at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, Whelan settled for 25 years in East Anglia. This North Sea region of England is a treasure trove of stained glass, rood screens, and wall paintings that survived the image-wreckers of the English Reformation. The imagery of medieval East Anglia was close in spirit to the artist’s own Celtic Catholic sensibility and love of caricature, inspiring his distinctive style of sacred art. Whelan made up his mind to bring art back into churches, reviving a tradition all but lost in the historical upheavals that made the modern world. His acrylic on panel painting from 2002 of The Martyrdom of St. Edmund is now a permanent fixture of the Lady Chapel in St. Edmundsbury Cathedral in Suffolk, England.

Whelan created fourteen images as a Stations of the Cross cycle about the life of Edith Cavell, the British nurse sentenced to death by German forces in Belgium in 1915 for aiding Allied soldiers. Displayed, first, in the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., to mark the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I in August 2014, the exhibit moved to the Cathedral of St Michael and St. Gudula in Brussels, the city where Cavell was tried, imprisoned, and executed, arriving at its final destination, the Anglican Cathedral in Norwich where Cavell is buried, for the centenary of her execution in October 2015. Normally on view in the Cathedral library, the Cavell painting cycle is displayed each year in the ambulatory on the anniversary of her death.

To commemorate the 15th anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2016, Whelan created the 275 x 365 cm. installation, Holy City, for the north transept of Washington’s National Cathedral, composed of nine separate panels with imaginary scenes of sites sacred to the three Abrahamic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Realizing a theme much on his mind since the events of 2001, Whelan designed the various cityscapes so they would form one harmonious vision of a New Jerusalem, where, as the artist says, “people can walk the streets of this Holy City and feel welcome.”

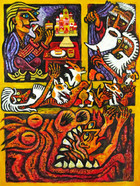

Whelan often uses the storyboard method to tell a biblical tale, derived as much from medieval art as contemporary filmmaking. In his version of Christ’s parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man in the Collection, the purple robe of the cake-eating glutton in this life provides a comfort blanket for the beggar in Abraham’s bosom. The sore-covered body of Lazarus spans and divides the canvas, reminding us just why the Rich Man is trapped in Hell. The dogs cross boundaries, seeking pastry crumbs fallen from the table, while nuzzling their way into Paradise. Whelan claims his corgi models have nothing to do with Britain’s royals and if the depiction of the Rich Man brings anyone to mind, keep it to yourself!

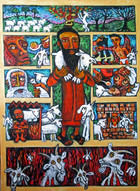

In Whelan's depiction of the Last Judgment from the 25th Chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, when the king, representing Christ, separates the sheep from the goats based on how they have treated "the least of these brothers and sisters of mine," sheeps and goats run rampant through illustrative boxes showing the hungry, the naked, the thirsty, the sick, the stranger, and the prisoner receiving comfort from anonymous hands. We know the goats are already in trouble from the way they have stripped the foliage off the trees of Paradise and lunged after forbidden fruit, but you cannot help but feel a tinge of remorse for their sorrowful fate, wondering if they have been judged a bit unfairly for being more ornery by nature than dumb and dutiful sheep.

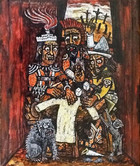

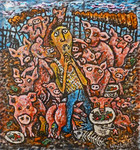

Now living in Connecticut, Whelan has been a willing, witty contributor to church exhibitions organized by the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection. For a show about eye-witnesses to the Crucifixion, he came up with the mixed media painting, The Die is Cast, showing loutish Roman soldiers shooting dice for an eerily animated robe of Christ, while a spike-collared canine and hell cat look on. In The Prodigal at Rock Bottom, a commissioned piece from Whelan for a show on this parable, puzzled porkers watch the odd human in their midst get converted amid the slop pails. In a spirit-rousing end to the pandemic year of 2021, he painted a portrait of The Sacred Art Pilgrim as a sea-faring Celtic monk in an art-laden coracle navigating storm-tossed seas with a divine wind at his back and the Blessed Isles in sight. This is divine comedy in the truest sense.