Wayne Forte

Wayne Forte can truly be called an artist of the Global Village. He was born in 1950 in the Philippines, raised and educated in Southern California, and married in Brazil. He has also studied at the Sorbonne in Paris, made prints in Florence, and taught in Orvieto, Italy. In crisscrossing continents and hemispheres, Forte believes his art-making has become “richer because it draws from a wide pool of influences, deeper because it takes into account various cultural perspectives.”

The artist’s Asian heritage is reflected in his appreciation for loose calligraphic line carried over into his paintings. From Latin America comes his love for the monumental, space-filling figures to be found in the murals of Mexican Social Realist Diego Riviera. His time spent in Europe deepened his understanding of Great Masters like Fra Angelico and Rubens, whose work he often “updates” in his art. As an American artist, he has been influenced by various trends of Modernism from Cubism to Conceptualism.

From an early age, Forte saw art-making as a religious activity. He remembers attending Mass in old Spanish mission churches when he was a child of five or six and creating decorative, small scale altars, hidden away in his bedroom closet. The artist had finished university courses and was making self-referential works full of alienation typical of the late 1970s in a Los Angeles studio, when a conversion experience on the island of Hawaii led Forte to look at art once again in sacred terms, this time as a tool for evangelizing the world.

Forte came to see his true calling was to bring art back into the Church after centuries of neglect and open hostility to images. He had to confront a challenge facing all artists of faith in the modern era. As he bluntly puts it: “The world doesn’t understand them, and the church doesn’t understand them.” Forte found a community of like-minded art-makers in Christians in the Visual Arts (CIVA) and joined an arts ministry in a non-denominational church near his home in Southern California. After nearly four decades of what he terms, “persistence and humility,” he remains true to his mission.

Forte became well-schooled in making “message art,” since his church projects often included illustrating sermon series. He sometimes had as little as a week to create images to accompany spoken words, and the quickly-rendered pieces put on display at worship services served as first drafts for more complete works, evolving over months, where he incorporated comments and criticisms from the community. PowerPoint projections have largely taken the place of sermon-based art these days, but Forte still shows his pieces in church exhibitions and creates site-specific works like painted wall-hangings.

Forte has developed a fluid and flexible style of art that he describes as “expressionistic, narrative and figurative.” To create a feeling of pent-up energy, he squeezes figures into confining spaces, as we see in his cropped variation in print of Ruben’s Deposition from the Cross. A contorted Mary with the Baby Jesus in arm struggles to break out of the box in the painting, Third World Madonna, inspired by a TV documentary on poverty in the Majority World. In Forte's meditation on the Eucharist on canvas, Remember Me, the artist boldly cuts off the upper part of Christ’s face to focus our attention on his wounded body, offered to us in the bread and the wine.

Forte likes to work in black and white with minimal coloring used to maximum effect. Taking a page from the Cubist copybook, he often incorporates text into his art. Flowing black brush strokes, bright splotches of red, and a screaming headline heighten the drama of the mixed media drawing, Father Forgive Them, where sketchy, nail-pierced hands reach heavenward in supplication from truncated arms in flesh-tones, extending horizontally from the Cross. With a wispy beard and pain-racked features, this face of Christ defies racial typing. In another labelled drawing, Lazarus and the Rich Man from the Gospel parable change places in a spin of the wheel of divine destiny.

The artist’s unique set of skills and worldwide view have made him an ideal partner for the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection in developing defining images for church art shows on social themes. For an exhibition of contemporary Advent art, Forte came up with a gritty, streetwise variation on traditional manger scenes in his mixed media drawing, Urban Nativity, where trash collectors stand in for the shepherds and the Virgin Mary keeps watch over the Baby Jesus, asleep in a tire in front of a tenderloin flop house, a poignant pose suggested by a newspaper photo of a mother and child during a famine in Somalia, tacked up on the wall of the artist’s studio.

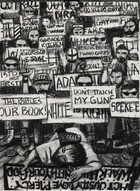

In Forte's drawing, Holy Family Immigration, the artist presents the Flight into Egypt narrative in the context of current immigration issues, showing us the silhouette of Joseph, Mary, the Baby Jesus, and a donkey from traditional imagery on the theme outlined against an ominous backdrop of jumbled warning signs, barbed wire, and cyclone fencing. At a time when public life in the U.S. has been dominated by religious-driven, single-issue political agendas, he shows what God really requires of us in the sketch, A Modern Day Prophet (Micah 6:8). Says Forte:“When Christianity is stretched to include all nations and denominations it functions as it should; when it becomes nationalistic it suffers under the spirit of fear."

During the past two decades, Forte has reconnected through his art with the homeland he left as a child of three, taking part in five shows in the Philippines, including a exhibition in Bacolod, capital of the Negros Occidental province, featuring twelve Filipino variations by Forte of the Madonna and Child. For a group exhibition in the historic city of Cebu of works made on traditional hand-woven Abaca cloth, Forte created a triptych of the Holy Trinity with simple black mark-making, where God the Father stands in a dugout canoe surveying a sea rich in aquatic life, while Christ casts a fishing net, and a feminine Holy Spirit bears an offering of fruit. In works of this kind, Forte amply illustrates that geographic borders may limit the flow of people but never artistic inspiration.