Helena Bochorakova-Dittrichova

(1894-1980)

The truest way to profile Helena Bochorakova-Dittrichova would simply be to show her portrait. The Czech printmaker’s aesthetic credo can be summed up in the old adage: “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Largely unknown outside her homeland, she was a pioneer of the “wordless book“ genre, creating 15 illustrated narratives without texts between 1929 and 1969. They range from childhood memoirs to U.S. travelogues to the Life of Christ. Long overdue international recognition finally came her way in 2014, when the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. devoted a solo exhibition to "the images that tell a story" of Bochorakova-Dittrichova, dubbing her “The First Woman Graphic Novelist.”

Bochorakova-Dittrichova belongs to a generation of Czech artists who lived through turbulent times. Born in the South Moravian town of Vyskov in 1894, she came of artistic age when the newly independent Czechoslovak Republic was undergoing national renewal after nearly 400 hundred years of Habsburg rule. She got caught up in this cultural renaissance, when she entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in 1919 as a student of graphic arts and encountered artistic movements popular in Europe at the time from Art Nouveau to Expressionism. After graduating, she received a scholarship from the Ministry of Education to study modern print-making in Paris, the first of many trips abroad that would take her from America to Asia Minor.

The aspiring Czech artist's arrival in the French capital coincided with a revival in wordless book making, led by the Belgian-born Printmaker, Frans Masereel, an art form dating back to the woodblock devotional tracts of the Middle Ages. A committed Socialist, Masereel honed his skills as a satirist drawing political cartoons while sitting out World War I in Switzerland and published a trail-blazing work in 1918, The Passion of a Man in 25 Woodcuts, in the Collection. In bold, black and white Expressionist woodcuts without text, he tells the story of a young worker born out of wedlock into poverty, who is executed after leading a revolt against exploiting industrialists. The association with the Passion of Christ is made explicit in the illuminated crucifix in the courtroom and in a tiny image on the cover of Christ carrying the Cross.

American Illustrator Lynd Ward was another ground-breaking proponent of this unusal art form, also represented in the Collection. He discovered Masereel’s wordless books, while studying art in Germany and brought the genre across the Atlantic, publishing Gods’ Man in 1929, the first American graphic novel. In 139 woodblock panels, Ward presented an Art Deco variation on the Faust legend, where an artist sells his soul for an immortal brush and comes to know fame, then, disillusionment in love and commerce. He flees a modern day Babylon to wed a woman of the mountains, losing everything when Death arrives to claim his due. As the plural “Gods’” in the title suggests, the hero contends with the demands of rival modern “deities.”

Bochorakova-Dittrichova ‘s first picture book, From My Childhood, appeared in the same year as Ward’s illustrated opus but is different in theme and style from the wordless works of the American artist and Masereel, depicting intimate scenes from the daily life of a young girl of the artist’s own provincial, middle class background. Her artistic vision would ultimately encompass more than the traditionally feminine domain of hearth and home. Bochorakova-Dittrichova exposed the historic injustice against Native Americans in Indians Then and Now (1934) and lauded the achievements of Soviet Socialism with images of collective farms and hydroelectric power stations in Impressions of the USSR (1934).

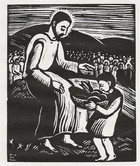

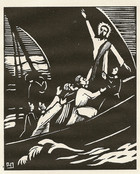

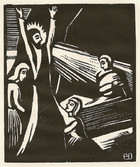

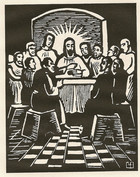

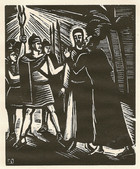

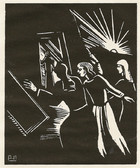

The Czech illustrator created one major religious work in the Collection, both elegant and eloquent in its simplicity. As the Nazi Occupation of her homeland in World War II was drawing to an end in 1944, Bochorakova-Dittrichova retold the Life of Christ in picture book form in Christ: 32 woodcuts from the New Testament. She devoted one image for each of the traditional number of years in the life of Jesus, beginning with the Annunciation and ending with the Ascension. Bound between publisher’s boards with unnumbered pages, a publication of this kind with minimal text would have passed more easily through strict German censorship.

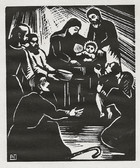

In a short essay introducing the wordless image pages, Czech Artist Frantisek Kubista linked the Bochorakova-Dittrichova album in its “purity” of style to Czech medieval illuminated manuscripts and in its mystical subject matter to the early 20th century religious works of Czech Symbolist August Bromse, who created his own print cycle of Christ imagery. In simple, black and white compositions like her folkloric nativity scene, Kubista believed the artist ”reveals to us in her own unique way the eternally radiant moments in the life of Christ, which illuminate our lives as well.”

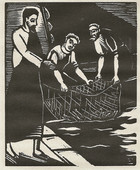

The selection of twelve images on display in the gallery from Bochorakova-Dittrichova's picture book of the Gospels shows her mastery of story-telling with an economy of visual means. In the plates depicting the stilling of the storm, the raising of Lazarus, and the coming of the women to the empty tomb on Easter morning, she has reduced line-making to an expressive minimum. White highlighting—those dug-out areas on the woodblock that hold no ink—define the compositions against broad areas of black. In keeping with the artist’s original intention, the prints are presented here without titles. Let them tell their own stories!