Antanas Kmieliauskas

(1932-2019)

The Littera Bookshop at the University of Vilnius in the capital of the Baltic republic of Lithuania must be the only campus textbook retailer in the world where you can find required course readings under a ceiling worthy of the Sistine Chapel. As students browse the bookshelves, ornately draped figures and well-muscled nudes in the style of Renaissance saints and sibyls look down from painted vaults representing astronomy, medicine, music, and art, while famous academicians and alumni peer out of rondels on their supporting arches. Seeing this visual tour-de-force in frescoes, commissioned to mark the 400th anniversary of the University’s founding in 1979, you can readily understand why its creator, Antanas Kmieliauskas, has been dubbed the Michelangelo of Lithuania.

Like the famous Florentine, Kmieliauskas was a master of many mediums, whose work is suffused with sacred story and the drama of his homeland’s troubled history. In a long and prolific career, Kmieliauskas created some 2000 square meters of wall paintings—over 1300 more than Michelangelo!—including the ceiling of the Rainiai Martyrdom Chapel commemorating the victims of a 1941 Soviet secret police massacre. Among his over 70 sculptural monuments is a pink granite statue of Jesus carrying the Cross on a Vilnius street where a human rights-activist priest died in 1981 in a dubious accident. Religious and patriotic themes also appear separately and intertwined in many of his 100 paintings and 420 book plates and prints.

Born into a small landholding family in southern Lithuania, Kmieliauskas grew up copying drawings by an artist uncle who died young. During the Nazi occupation in World War II, his abilities were spotted by a Roman Catholic priest, who had given the pupils in his religion class the assignment of drawing the Bethlehem manger. The cleric was so impressed by the Nativity scene Antanas copied from one of his grandmother’s religious magazines he asked the young man to make artworks for the Church of the Savior in the village of Butrimonys. When the Soviets established control in Lithuania after 1944, Kmieliauskas provided illustrations for anti-Communist partisan publications, while studying at the Kaunas Secondary Art School.

Despite his anti-Soviet “extra-curricular” activities, Kmieliauskas graduated in 1951 with a gold medal and went on to study painting at the State Art Institute of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Lithuania in Vilnius. He ran afoul of the Communist regime in 1959, when he created his first large sculpture for the historic St. Nicholas Church in Vilnius, a statue of St. Christopher with the inscription: Holy Christopher, Keep Watch Over Your City. Soviet officials had banned the historic emblem of Vilnius with its image of this patron saint, and Kmieliauskas was expelled from the Lithuanian Union of Artists, denied exhibitions and other privileges bestowed on official art-makers. He supported his family by taking on private commissions for grave stones.

A reversal in the artist’s fortunes came about thanks to his ex-libris book plates. These small format prints were a favored medium of graphic artists in Soviet-dominated East Europe, since they could be easily circulated, often as greeting cards with PF (Pour Feliciter) markings, and evade state censorship. Kmieliauskas submitted his first book plate to an exhibition in Czechoslovakia in 1966 and received third prize in a Hungarian competition four years later. Cultural bureaucrats could no longer ignore his growing international reputation, when he took first place in a 1974 contest in San Vito al Tagliamento, Italy. The next year Kmieliauskas was admitted back into the Union of Artists and a teaching post followed at the State Art Institute.

After Lithuania declared its independence from the Soviet Union in 1990, Kmieliauskas became a prophet-artist honored in his own country. His murals linking the Passion of Christ to the suffering of the Lithuanian people in the Rainiai chapel earned him the National Culture and Art award in 1994. Kmieliauskas received both the Order of the Grand Duke Gediminas from the Lithuanian President and the Order of St. Gregory the Great from Pope Benedict XVI in 2007. The fame late in life left him unfazed. Kmieliauskas told an interviewer he saw himself as a “white crow,” an art-maker who had always stood out from the crowd and pursued his own course, even if he was out-of-step with the times.

The sampling of prints on religious themes from the Collection displayed here—ex libris, PF cards, and regular format plates—show just how versatile and innovative Kmieliauskas was as a graphic artist. They can best be described as mixed media works, often with the textured surfaces of collagraphs, as we see in the earliest piece in our listings, a 1968 book plate of St. George killing the dragon with a grey mesh background and raised, pitted areas in ochre. The Archangel Michael has the look of a crudely-dabbed, time-worn wall painting in a similarly-styled 1969 ex-libris. In a multi-layered bookplate of Christ carrying the Cross from 1982, Kmieliauskas abandons conventional rectangular framing to let the image sprawl across the page.

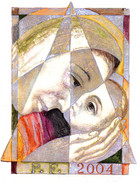

At the end of the 1980s, The Lithuanian print-maker’s images took on a different look, as if composed from multi-colored, mismatched glazed tiles, a style first seen in the collection in a 1988 ex-libris of St. Francis preaching to the birds. This geometric building-block effect appears again in a Mocking of Christ bookplate from 1991 and a Nativity scene from 1996. Judging from photographs in a 2010 blog by a visitor to the artist’s studio, Kmieliauskas built up these plates out of separate components with different textures, layers, and depths of cutting, fitting them together like pieces in a puzzle. We can actually view a plate of this kind in the blog side by side with the print of a triangular Madonna and Child in the Collection.

Images of the Virgin Mary hold a special place among the sacred works of this artist whose devoutly Catholic homeland borders on Poland. Another triangular study of the Madonna and Child can be found in the gallery along with a trio of close-up portraits of a somber, contemplative Mary on greeting cards from 2004, 2005, and 2006, where the ink appears to have been applied in brush strokes. Another recurring motif is the Pensive Christ, a popular subject in East European folk art of the Passion, where a weary Christ on his way to Calvary sits with his head resting in his hand. We see the theme in a crudely textured variant, probably dating from his early period, a more fully realized version from 1972, a majestic depiction from 1985, and a close-up of the Sacred Head from 2000 in the style of the Virgin portraits.

Passion motifs combine with Marian imagery in a trio of prints of Pieta. Kmieliauskas paid homage to his Renaissance “mentor” in a 1981 ex libris of Michelangelo’s Rondanini sculpture. A second bookplate of Pieta from 1999 shows Mary holding the broken body of Christ on her lap, her heart pierced by the swords of her seven sorrows, wounding moments in her life as the Virgin Mother, a popular theme of Catholic devotions. This baroquely ornamental piece is a smaller variation on a standard sized print that is the crown jewel of my Kmieliauskas collection, a Lithuanian Pieta made in the year the artist’s homeland freed itself from Soviet domination.

Recessed behind the central cross with the Virgin and her wounded heart are what appear to be four story-telling bas-reliefs. In the upper left and lower right, we can make out the shapes of totemic animals from the country’s pre-Christian past and a Lamentation scene from the Passion of Christ. On the lower left Lithuanians are being herded with Soviet rifle butts into cattle cars for deportation to forced labor camps of the Gulag Archipelago, marked by crosses on a map of eastern Siberia on the upper right. The artist’s love of God and love of country come together in this patriotic altarpiece in graphic form in subdued shades of blue, purple, yellow and gold.

St. George Killing the Dragon (1968)

The Archangel Michael (1969)

The Cross Bearer (1982)

St. Francis Preaches to the Birds (1988)

The Mocking of Christ (1991)

Nativity Scene (1996)

Madonna and Child

Madonna and Child (2004)

Pensive Madonna (2005)

Madonna and Child (2006)

Pensive Christ

Pensive Christ (1972)

Pensive Christ (1995)

Pensive Christ (2000)

Pieta After Michelangelo (1981)

Pieta (1999)