Nikola and Milen Litchkov

Nikola (b. 1940)

Milen (b. 1972)

Sculptor Nikola Litchkov can be found most days of the week from ten in the morning until six in the evening in the Miniature Gallery at 55 Prince Boris the First Street, a tree-lined thoroughfare in a residential district within walking distance of the historic center of Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria. Cast-metal figure groupings, which Nikola models in plaster in his basement studio, occupy shelves, pedestals, and plinths in the street-level showroom. Nicola's son, Milen, created the paintings and prints in an expressionist, folk art style that hang on the walls of this small, family-run art enterprise, made possible by the collapse of Communism in the Balkan nation in 1989.

Setting up their own art gallery was no small achievement for the Litchkov family. Born in 1940 in the Bulgarian community of Zurnevo in Northeastern Greece, Nikola was a child when his family fled across the border to their ethnic homeland, when the Nazi Occupation of World War II was followed by the Greek Civil War. At 13, he lost his hearing due to a congenital disorder. Nikola taught himself shoemaking but was skilled enough in painting to gain entry to the National Academy of Arts in Sofia. He found his real talent was for sculpting, an art form he would pursue with success in the Communist era, receiving commissions for public monuments.

Born in 1972 in Sofia, Milen suffers from his father’s hereditary ailment. Limited in his activities as a child, he became an avid reader and learned from his father how to draw and paint. Milen’s plans to study law fell through when he had to be hospitalized. A nurse led him in his time of despair to faith in Christ. Milen decided to follow his father in art-making and specialized in graphic arts at the National Academy of Arts. He works at home now on his finely rendered linocuts, drypoints, and etchings, a large number on biblical themes. Milen belongs to the Union of Evangelical Congregational Churches in Bulgaria. Nikola is Bulgarian Orthodox. The two of them, says Milen, “live in peace and full understanding.”

Father Nikola’s sculptures combine the raw expressiveness and rounded solidity of the French early modern masters, Auguste Rodin and Aristide Maillol, with the Socialist Realism in which he was schooled in the Communist era. In the pieces on religious themes in the Collection, he widens his focus from the small group studies on display in his showroom to encompass milling crowds in The Return of the Prodigal Son and The Triumphal Entry. Roughly-finished figures gather en masse to watch these unfolding sacred dramas, distinguished by their gestures. Christ is high and lifted up in The Crucifixion, his head lowered toward the watchers at Golgotha. One kneels clinging to the cross; others wave their hands in despair; many are simply motionless lumps. They make up a single form with emotive variations.

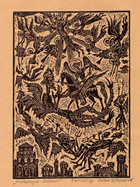

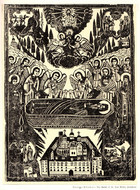

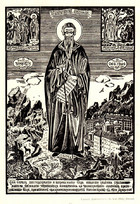

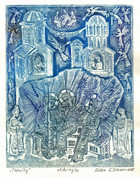

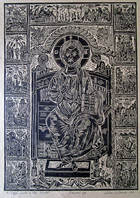

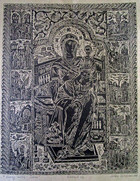

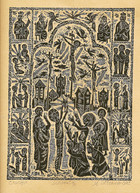

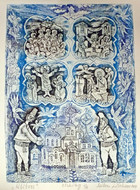

Son Milen works not with broad gestures but details. His graphic art pays homage to the miniaturist illuminators of Bulgarian sacred manuscripts like the 14th century Gospels of Tsar Ivan Alexander. In his linocuts, Christ, Ruler of the World, Mary with Jesus, and Crucifix, he copies Eastern Orthodox “life-story” icons where the central image is framed with cartoon-like narrative panels. The retro look of prints like The Nativity with its out-of-scale figures in flat perspective suggests 19th century Bulgarian religious woodcuts from the village of Samokov and linocuts made by modern interpreters of this “National Revival” style like Vassil Zakhariev. Other contemporary Bulgarian artists who have influenced Milen's work are Ivan Milev and Dimitar Kazakov.

Sacred themes often mix with folklore motifs in Milen's prints. In one color etching, traditional Christmas carolers with handcarved shepherd's crooks in capes and kalpak hats process through a fantastical Byzantine town while Christ and a quartet of angels peer down from heaven. Scenes from an illuminated Gospel appear above prosperous patrons in embroidered waistcoats and strapped tsarvuli sandals who show off the church they have built. Another etching presents peasant women in festive double aprons drawing water from a village well, unaware of the divine drama unfolding above, where angels and the Holy Trinity witness the dragon-killing thrust of St. George, whose feast day is a national holiday in Bulgaria.

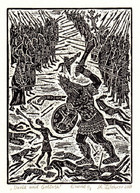

As a labor of love, Milen has created enough prints to illustrate a Bible. Beginning with the Garden of Eden, Noah's Ark, and the Tower of Babel, he has depicted a whole series of classic stories from the Hebrew Scriptures like David and Goliath, Elijah and the Fiery Chariot, and Jonah and the Great Fish. A linocut of the Annunciation begins a New Testament cycle, followed by images of the Birth of Christ, the Baptism of the Christ, the Calming of the Storm, and the Raising of Lazarus. Prints of the Passion of Christ illustrate the Triumphal Entry, Last Supper, Crucifixion, and Resurrection. There are even apocalyptic images of the Rapture of the Church and the Archangel Michael’s War in Heaven. Says Milen: “If I devoted my whole life to Bible stories, I could only illustrate a small part of them!”

Nikola Litchkov

Nikola Litchkov

Nikola Litchkov

Georgi Klinkov

Vassil Zakhariev

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov

Milen Litchkov