David Wojkowicz

(1967-2022)

David Wojkowicz challenged the way we visualize sacred narrative. In an age when we have grown lazy from easy access to cliched, ready-made, representational imagery, the Czech digital artist required us to use our imagination, when viewing his abstract depictions of biblical texts. We see their simple geometric forms and basic outlines. Our job is to reconfigure them in our mind’s eye in ways that add new insights into the scriptural passages they illustrate. As Wojkowicz once explained: “The goal of abstract art is to allow an audience to appreciate paintings without the need for detailed explanations.”

Born in Prague in 1967 as David Nebesky, the artist who adopted the pseudonym of Wojkowicz was originally a man of words, not images. Following the fall of the Communist regime in 1989, Nebesky studied theology at the historic Charles University in the Czech capital with a special interest in the development of Christian doctrine and canon law. He set up a charity in 1990, where he sometimes worked, offering Christian literature as audio books to the visually impaired. It was his passion for photography, especially taking black and white images of the sea while living in England, which opened the door to abstract digital art.

Capturing the ebb and flow of wave and tide on film fired the imagination of this hobby photographer from a landlocked nation of Central Europe, leading him toward an increasing abstraction of form. When the soon-to-be printmaker, Wojkowicz, realized he was looking through his view finder for scenes in the natural world, fitting preconceived images in his mind, he decided to cut himself loose from photography and make non-representational art. For the trained theologian, these mental images became more than pure abstractions. He saw them as visualizations of scriptural passages that would come together in an illustrated Bible.

Wojkowicz made art using a method he developed with graphic vector software. None of his digital art pieces was generated automatically. He used the most basic drawing tools to create each visual element in his prints. Working with a muted color palette and low contrast, he would merge seven or more partial images into one. The dissimilarities in the layered patterns gave depth to the final composition. Reading the Bible or hearing a passage read in church, he would “see” shapes coming together for a new piece of art but never in a random way. As Wojkowicz put it: “There is always some symbolism and mathematics behind every one of my images.”

Many of the new media artist's abstract pieces are readily accessible to viewers. It is not hard to envision Joseph, Mary and the Christ child in the cubistic composition of The Nativity (Matthew 1:18) or the Wise Men in shadow before A Star in the East. In The Letter and the Spirit (2 Corinthians 3: 6b) a curvilinear form like a sprouting seed stands out against an inert rectangular brown background. Blended stripes of warm colors on a deep blue-purple background evoke lanterns at a nighttime vigil in Waiting for Christ (Jude 1:20-21). The peaks and troughs in the massive blocks of A Voice in the Wilderness (Isaiah 40: 3-4) resemble seismographic markings that indicate just how earth-shaking this message will be.

Other purely abstract images free our minds from distracting associations and move us to a new level of awareness of the mysteries of the cosmos. In The First Day (Genesis 1:3-5) white and black triangles on a globular form in shards of blue suggest the separation of day from night at the beginning of Creation. Wojkowicz layers textured squares of increasingly lighter shades of green as the verdant background for a trefoil arrow pointed at a dark circle in Logos (John 1:1-2), evoking the New Testament origins story. In the blue on blue squares within squares of Talking Heavens (Psalm 19: 1-4), we see the building blocks of the universe telling of the glory of God.

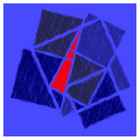

The prints come with titles and biblical texts that can serve as interpretive tools. The grid of crisscrossing lines in Following Jesus (Mark 8:34-35) makes immediate sense when we learn the Gospel passage talks about taking up your cross. Looking at Man of Sorrows (Isaiah 53:3) you might see the brilliant red triangle surrounded by dark geometric forms as a variation of Mocking of Christ imagery. The red wedge might also suggest the wound in Christ's side or even his Sacred Heart.

Wojkowicz did not intend his biblical prints to be visual puzzles to be solved or riddles with one right answer. They can have meanings as multiple as there are viewers. He believed "a true artist is not someone who understands their art better than anyone else." His death after a brief illness at 55 has left the sacred art world all the poorer for the loss of his unique way of expounding holy texts with contemplative abstract images.