Wilhelm Geyer

(1900-1968)

Wilhelm Geyer ranks among the great sacred artists of the 20th century. After finishing his studies in 1923 in the Art Academy of Stuttgart, the Southwest German city where he was born, Geyer immediately embarked on a series of large, multi-paneled altar pieces, painted in such a ferociously early modernist style, he was dubbed an “ecstatic” expressionist by admirers and labelled a “degenerate” by the Nazi regime. Geyer designed his first stained glass windows in 1935 and went on to create more than 800 windows for over 150 churches, including Cologne Cathedral and the Minster in Ulm, playing a pivotal role in the construction and refurbishment of places of worship in post-World War II Germany.

This life devoted to sacred art hung in the balance for 100 days in 1943, when Geyer was detained by the Gestapo for suspected involvement in the White Rose anti-Nazi group, following the arrest and execution in February of Hans and Sophie Scholl, sibling co-conspirators, caught handing out leaflets at the University of Munich. Geyer knew the Scholl family from Ulm, the South German city where he lived most of his life, and Hans had helped him find a studio in Munich, while Geyer was working on a church commission. The White Rose bulletins came from a printing press concealed in the basement. Geyer, the father of six children, was shielded by the Scholls from direct involvement in the protest and was released in July 1943 for lack of evidence.

Geyer made no secret of his opposition to the ideology of the Third Reich, so diametrically opposed to his Roman Catholic convictions. He is represented in the Collection by the 1939-1940 portfolio of 53 double-paged “stone drawings,” Pictorial Thoughts on the Sunday Gospels, illustrating the Gospel readings in the Catholic lectionary for each Sunday of the year, beginning with the First Sunday after Pentecost through Pentecost Sunday. The image series has all the earmarks of a “self-printed” book with the credit text and titles on the folded sheets created on a typewriter and the unbound pages gathered in a standard document folder. Geyer distributed the printed images each week to a small circle of friends, circumventing official censorship.

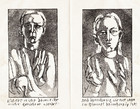

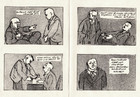

Daily life in the Third Reich serves as the setting for many Geyer Gospel illustrations. The “field” where the seed is scattered in the Parable of the Sower in Luke 8 could be a pedestrian-filled street in Munich or Berlin. Recast as a typical German civil servant, the cheating accountant in Christ’s Parable of the Dishonest Steward in Luke 16 ensures his future by offering a cut-rate debt repayment deal to another faceless bureaucrat. In Geyer's illustration for Christ’s dictum in Matthew 6: 24-33 to “seek first the kingdom of God,” a man has left a well-appointed sitting room with its centrally placed Volksempfanger radio for receiving Nazi propaganda broadcasts to find a private place to kneel in prayer.

We see glimpses of the dark side of Hitler’s Germany in Geyer’s depiction of the Parable of the Wheat and the Tares in Matthew 13, where the sower of good seed by day is diabolically transformed into the figure of the evil enemy, planting weeds by night. The seven demons who return with the one who had been exorcised to possess a man in the image for Luke 11: 24-26 look like a hit squad of horn-headed, brown-shirt thugs. John the Baptist languishes naked in a grid-barred cell like a political prisoner in the artist’s illustration for the reading from Matthew 11 where Jesus praises the incarcerated prophet who was sent as his forerunner.

The horrors of the Fascist police state find full expression in a suite of 20 lithographic drawings of the Passion of Christ included in the Pictorial Thoughts portfolio. Geyer uses violent, slashing lines to depict moments when Jesus is manhandled, flogged and stripped naked. He is the prototype of all innocent sufferers of systemic violence, his facial features often left unfinished or blackened out. We glimpse on-lookers peeping around doorways or averting their eyes from the brutality. Framing an image of Christ awaiting trial, Peter and Judas seem to mime “see no evil” and “hear no evil.” John, Mary Magdalene, and the Virgin Mary leave Golgotha in the final drawing. The Mother of Christ, staring fixedly ahead, will certainly hold this day in remembrance.

Two prints from this period in the Collection of a sleeping child and a mother feeding her baby offer a glimpse of the private Geyer, the dedicated husband and father. His son, Wilhelm, spoke to German school groups in later years about the family’s ordeal during the artist’s imprisonment, when they were told he was “on death row.” Geyer’s five surviving children, aged from 76 to 89, reunited in 2018 in the Southwest German town of Boblingen for the opening of the exhibition, Ecstasy: Wilhelm Geyer and His Works in Paint, marking the 50th anniversary of their father’s death. It was a fitting tribute to this man of faith, conscience, and courage who had well-nigh miraculously escaped the fate of so many of his contemporaries.

Pictorial Thoughts Title Page

Pictorial Thoughts Document Folder

Pictorial Thoughts Typewritten Texts

First Sunday after Pentecost: Luke 6:36-42

Eight Sunday after Pentecost: Luke 16:1-9

Fourteenth Sunday after Pentecost: Matthew 6:24-33

Second Sunday of Advent: Matthew 11:2-10

Fifth Sunday after Epiphany: Matthew 13:24-30

Sexagesima Sunday: Luke 8:4-15

Third Sunday in Lent: Luke 11:14-28

Pentecost Sunday: John 14:23-31

Passion of Christ V

Passion of Christ VI

Passion of Christ VII

Passion of Christ X

Passion of Christ XII

Passion of Christ XIII

Passion of Christ XIV

Passion of Christ XV

Passion of Christ XVI

Passion of Christ XX

Sleeping Child