Jean Cocteau

(1889-1963)

The entrance to Notre Dame de France Church at 5 Leicester Place is easy to miss within its non-descript postwar housing block façade, wedged between the Prince Charles Cinema complex and a row of eateries in London’s Soho entertainment district. Awaiting the visitor on the left hand wall of the church’s spacious rotunda interior is a jewel box Lady Chapel with murals by French Artist Jean Cocteau, painted in less than two weeks in November 1959. Flanked by panels of the Annunciation and the Assumption is a central image of the grieving Virgin Mary at the foot of the Cross in the artist’s neo-classical Grecian drawing style. Cocteau also depicts himself at Golgotha in a display of devotion and self-promotion, typical of this multi-talented enfant terrible of 20th century French culture.

Cocteau made his mark in an extraordinary variety of artistic disciplines. He is, perhaps, best known as the director of the 1946 visionary film version of Beauty and the Beast with its arresting image of living arms holding candelabras. Already in 1917, his name was linked with Pablo Picasso and Erik Satie as the scenario writer of the Cubist ballet, Parade, staged by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. International stars from Anna Magnani to Ingrid Bergman have essayed the demanding role of a woman breaking up with her lover by telephone in Cocteau’s 1930 dramatic monologue, The Human Voice. He even sketched his own variation on the French national icon of Marianne for a 1961 postage state.

As an art-critic, choreographer, costumer, draughtsman, jeweler, journalist, librettist, movie-maker, muralist, novelist, painter, photographer, poet, playwright, scenarist, set-designer and even prize-fighter manager, Cocteau was dismissed by his critics as a superficial Jean-of-all-trades. For many, his life, itself, was an artistic creation, lived with an eye for the limelight, enveloped in the scandals of his openly gay lifestyle with celebrity partners like the matinee idol, Jean Marais, and his longtime opium addiction, chronicled in confessional memoirs. A brilliant conversationalist, mimic, and coiner of bon mots, Cocteau once famously said that “audacity consists in knowing just how far one can go too far.”

Figuring in the Cocteau life drama was a drug-cleansed return to the Roman Catholic Church in 1925 under the guidance of Thomist Philosopher Jacques Maritain and his wife, Raisa, whose home in the Paris suburb of Meudon was a spiritual refuge for French artists in the interwar period. In an exchange of letters with Maritain, Cocteau described “the embarrassment of treading on the Blessed Virgin’s robes at every step” of his religious renewal. His missives to Maritain describe drug-taking in sensuous detail, and he reached for his opium pipe again as he was finishing these spiritual musings, published in the jointly-authored, Art and Faith, in 1948.

However wobbly Cocteau’s “conversion” might have been, he remained connected to Maritain and the Catholic faith all his life—in his own self-referential way. The artist drew more deeply from Greek mythology in major theatrical and cinematic reinterpretations of the stories of Antigone, Oedipus Rex, and Orpheus, but Christian motifs define key works like, Crucifixion, his 25-stanza poem in free verse from 1946, represented in the Collection by a 1963 LP recording for which Cocteau designed the jacket with Christ in profile in a mesh of ladders. The artist appears by the Crucified Christ in a 1956 lithograph--simply titled, Jean—where Cocteau’s face from a 1952 self-portrait shares curly locks with John the Apostle from a Crucifixion scene by Renaissance Master Andrea Mantegna.

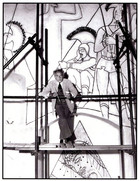

Cocteau’s religious art is monumental. In 1956-1957, he covered the interior of a chapel turned storage shed for fisherman in the Riviera port of Villefranche-sur-Mer with paintings of their patron, St. Peter. Along with the Soho murals, he created a herbarium of medicinal plants and Passion imagery in 1959 on the walls of a medieval chapel-leprosarium in Milly-la-Foret, the town near Paris where he spent his last years. Cocteau’s death in 1963 cut short his work decorating the Chapel of Notre Dame de Jerusalem in the Riviera commune of Frejus (completed by his “adoptive son,” Edouard Dermit), but he finished designs for a stained glass cycle on “immortality” for St. Maximin Church in the Northeastern city of Metz.

Restoring the chapel in Villefranche-sur-Mer was a labor of love for Cocteau. He had stayed at the nearby Welcome Hotel in the 1920s and 1930s, a notorious port-of-call where he mourned the death of his companion, the boy-genius writer, Raymond Radiguet, wrestling with religious faith and his drug habit. Lithographs in the Collection reproduce Cocteau’s designs for the chapel’s five interior murals. Women sort fish on the waterfront, while angels, like gulls, make sport in the sky above in one of two local color scenes. An angel (featured in a promotional poster) frees the imprisoned Peter in one from the trio of biblical wall paintings. The figure of Truth counts the number of Peter’s denials on her fingers from another mural of his rejection of Christ, who is depicted in one of fifty-some preparatory portraits Cocteau made for the project.

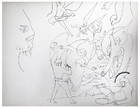

Sacred themes were much on Cocteau’s mind in his final year. He collaborated with French Artist Raymond Moretti on lithographs that included a Crucifixion scene and portrait of Christ as the Man of Sorrows. For Cocteau, sketching was like automatic writing, as if a pencil were grafted to his hand. Two highlights of the Collection are original drawings of Pieta and Christ on the Cross, the latter, dated 1963. There is a feeling of poignant immediacy in each, as if rendered quickly with single, unbroken lines. When the Francophone American Catholic Writer, Julien Green, visited Cocteau after what would prove a fatal heart attack in the summer of 1963, he noticed this perennial Prodigal Son of the Church kept an image of the Virgin Mary and a crucifix by his bed.

The Crucifixion of Jean Cocteau from Andre Maurice (album cover)

Jean

Cocteau Painting Chapel in Milly-la-Foret

La Chapelle Saint Pierre Villefranche sur Mer (cover)

Demoiselles de Villefranche

An Angel Rescues Saint Peter

Villefranche sur Mer: Chapelle St. Pierre

The Truth (from the Denial of Peter)

Study for Christ Portrait

Jesus Christ on the Cross

Face of Christ

Couple I (Pieta)