Bernard Buffet

(1928-1999)

In a grubby canadienne sports coat with cigarette grafted to his lip, Artist Bernard Buffet embodied post-war Parisian existentialist chic, befitting his trend-setting place in “France’s Fabulous Young Five” with Actress Brigitte Bardot, Novelist Francoise Sagan, Designer Yves Saint Laurent, and Film Director Roger Vadim. A child of the Nazi Occupation, Buffet painted gauntly elongated, angular figures in minimal settings in a style described as “miserabilism” that captured the mood of a nation coming to terms with World War II. For a time, he seemed to be nipping at the very heels of Picasso, gaining the number one spot in a French art journal’s 1955 list of the ten best post war artists. At 28, the celebrity painter already had his own chateau and Rolls Royce.

Success would spoil Buffet. His spidery signature on affordable prints of morose clowns and spindly bouquets was becoming too well known for the liking of French aesthetes. When Novelist Andre Malraux became France’s first Minister of Culture in 1958 with a mission to turn Paris into an international hub of abstract art, Buffet had to make way for Jean Dubuffet and other cutting edge Modernists. His figurative expressionist style would be acclaimed in Japan, where a museum dedicated to his work opened in 1973, but his rehabilitation in France only came in 2009 when the first major French retrospective of Buffet’s work since the late 1960s opened in Marseilles.

Shunned by the artistic elite, Buffet continued to make art in his own way for his own market, producing over 8,000 works in his lifetime. Critics accused him of constantly repeating himself. If the style of this stubbornly figurative artist remained largely unchanged, Buffet was highly inventive down the years in the choice of subject for his annual February solo exhibition, a feature of his exclusive contract in 1948 with Gallerist Maurice Garnier, who would represent only Buffet after 1977. They ranged from bathers at beaches to Dante’s inferno, and bullfighters at la corrida to the churches of France. Ghoulish glimpses of the horrors of war one year would alternate with a look at circus life.

One French art critic has described Buffet as “a primitive Christian witnessing modern misery.” He was not religious in a conventional sense but early Jesuit schooling and a devoutly Roman Catholic mother left their indelible mark. The painter’s first February show on a single subject in 1952 was devoted to the Passion of Christ. Scenes of the Flagellation, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection on three 280 x 500 cm. canvases unfold in empty expanses of existentialist twilight devoid of any religious trappings, where attenuated figures, the women in mourning garb, the men stripped to undergarments, commit acts of violence or mime gestures of grief.

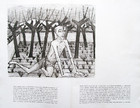

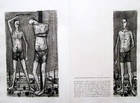

Similar motifs appear in the 21 drypoints Buffet created as illustrations for a 1954 printing in portfolio format of a Passion of Christ text, compiled from various biblical passages by the French Greek Scholar, Charles Astruc. An emaciated figure with shaved head, Christ brings to mind countless anonymous concentration camp victims as he endures the agonies of Holy Week alone, his haggard features a study in cosmic angst. Buffet sets the scene in a ruggedly stylized landscape, evoking the region of Provence, where the artist was living at the time in a farmhouse with Pierre Berge, who would later partner with St. Laurent to expand his fashion empire.

One of the more unusual items in the Collection is the original copper plate of Buffet’s engraving of the Crucifixion from the portfolio where the artist shows himself a skilled draughtsman with an engraving needle, bringing out expressive details of face and form amid meticulously rendered sections of cross-hatching. Two other artworks in the Buffet listings are related to the Passion of Christ cycle—the 1953 drypoint etching, Holy Face, differing slightly from the image of Christ imprinted on the Veil of Veronica in the text, and The Paschal Lamb, a 1967 reprint from the Mourlot Studios of a lithographic version of the endplate.

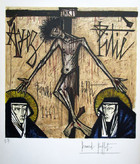

At the end of the 1940s, leading French artists turned to chapel decoration. Matisse designed stain glass, furnishings, and vestments from 1947 to 1951 for the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence; Picasso painted murals in 1952 for a Temple of Peace in Vallauris; and Jean Cocteau refurbished a derelict chapel in Villefranche-sur-Mer in 1957. Buffet followed suit in 1961with a cycle of murals on canvas of the life of Christ for a chapel on the grounds of Chateau L’Arc near Aix-en-Provence, where he came to live in 1958 with his new bride, Annabel Schwob, a writer-chanteuse who would be his model, muse, and mainstay for the next forty years.

The Chateau L’Arc Chapel paintings, displayed at Buffet’s solo show in February 1962, seem like Spanish Baroque studies, compared with his minimalist Passion scenes exhibited a decade earlier. As can be seen in a lithographic version of the Have Mercy wall canvas, the elongated angularity of the human figures so evident in Buffet’s earlier cycle is accentuated here with aggressive black linework. The striated haloes and voluminous garments weigh down a composition, seething with energy and emotion. His head decked in a live-wire crown of thorns, Christ tears his hands free of the nails on the Cross to reach out to the mourning women.

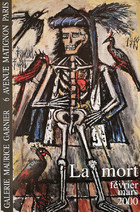

The Chateau L’Arc Chapel paintings found their way into the permanent art collection of the Vatican at the behest of Pope Paul VI’s private secretary. Buffet would never undertake another sacred art project of such majesty and magnitude, turning out the occasional print or poster on religious themes. Diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1997, Buffet dreaded a future without art-making and chose Death as the theme of his solo show for February 2000. One painting shows a skeleton kneeling in prayer at an altar with cross and monstrance. The artist committed suicide on October 4. 1999, found suffocated in a black bag with his trademark signature.

La Passion du Christ: Gethsemane

La Passion du Christ: Flagellation

La Passion du Christ: The Mocking

La Passion du Christ: Cross Bearing

La Passion du Christ: Deposition

La Passion du Christ: Resurrection

Engraved Copper Plate for La Passion du Christ: Crucifixon

Engraved Copper Plate and Crucifixion Drypoint

La Passion du Christ: Holy Face

Holy Face

La Passion du Christ: Paschal Lamb

Paschal Lamb

Bernard Buffet: La Chapelle de chateau L’Arc: Cover

Bernard Buffet: La Chapelle de chateau L’Arc: Plate VI

Bernard Buffet: La Chapelle de chateau L’Arc: Plate VIII

Bernard Buffet: La Chapelle de chateau L’Arc: Plate XVIII

Have Mercy

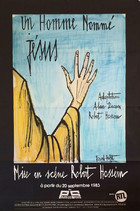

The Man Called Jesus