Kreg Yingst

In an age of virtual imaging and non-fungible tokens, Kreg Yingst makes the kind of art you can have and hold. The Florida-based graphic artist may use a computer now and then to experiment with designs and text lay-outs, but he takes pride in his “old school” approach to his craft. He works from sketches transferred onto wood or linoleum blocks, cutting away areas with gouging tools that will appear white in the finished pieces. Then, he makes prints off the inked blocks with a hand-cranked press, sometimes creating the impressions with a wooden spoon. Says Yingst: “I like the fact that someone can receive something made directly from my hand.”

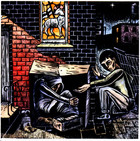

A native of Illinois, Yingst studied art at Trinity University in Texas and at Eastern Illinois University. He was a high school teacher for 13 years, before deciding in 2003 to make art full time. Trained as a painter, Yingst developed a passion for relief block prints, after discovering the boldly contrasting black and white wordless woodcut novels of Belgian Illustrator Frans Masereel and his American counterpart, Lynd Ward. The works of the German Expressionists and Mexican Social Realists inspired Yingst to add text to the visual mix. Like these movements, he makes “message art,” informed by issues of social justice like his backstreets Nativity scene.

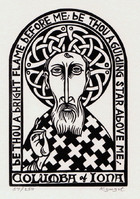

Yingst is best known for his narrative prints playing off music lyrics, composed in the retro format of posters or record album and CD covers. He has offered collectors a nostalgic browse through music-shop-like bins of prints at 18-some yearly art festivals around the country. When Yingst developed a more visible on-line presence during the pandemic, he found a surprisingly large audience for his body of work on sacred themes, ranging from portraits of the Virgin Mary and Celtic saints to illustrations of the Psalms and the life of Saint Francis of Assisi with special suites of prints on the Passion of Christ.

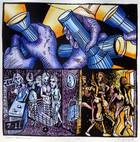

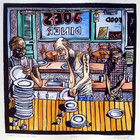

Hand-colored woodcuts in the Collection offering a modern spin on the Parables show the expressive range of Yingst’s wordless narrative pieces. The tale of the Good Samaritan is recast as an encounter between an African-American man of the streets and a Ku Klux Klansman. In an offbeat version of the story of Lazarus and the Rich Man, a physically-challenged beggar grabs for the cigarette butts tossed by a limo rider. The smart women in the Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins are those waiting with Energizer batteries in their flashlights for the late night arrival of the Bridegroom. In the artist’s take on the Parable of the Vineyard Workers, the hired hands deal with varying piles of greasy plates in a hash house.

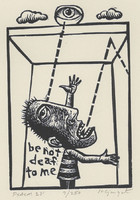

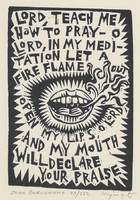

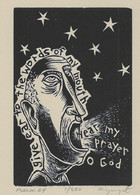

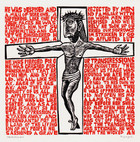

Yingst uses text not only to communicate ideas; he sees lettering as “shape to enhance composition.” In a printed prayer from the 16th century Belgian Jesuit Saint, John Berchmans, words seem to roll out in shockwaves from a mouth spewing fire. A plea for divine help enfolds the despairing supplicant and glows in the starry night in a visualization of Psalm 54. A line from Psalm 84 encloses two nesting birds. In a block print of the Crucifixion, the framing text of the Song of the Suffering Servant from Isaiah 53 firmly fixes the Dying Christ in the prophetic tradition in the Hebrew Scriptures of a Messiah who sacrifices himself to redeem the world. At a glance, the ranks of red letters look like massed humanity.

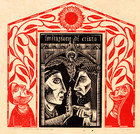

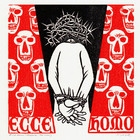

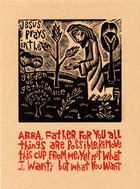

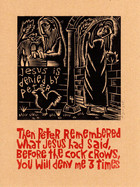

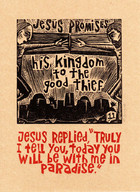

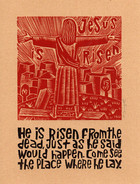

The Crucified Christ is part of a print series paying homage to Northern Renaissance Master Albrecht Durer who created Great and Small Passion woodcut suites. The block prints from Yingst owe more to German Expressionism than 16th century Nuremberg. In his variation on Ecce Homo, we see the thorn-crowned, tethered Christ from behind engulfed by simian skull faces. For the 2021 Lenten Season, Yingst created a “biblical” Stations of the Cross cycle with commentary, beginning in Gethsemane and ending with the Resurrection, This version omits traditional subjects like the Veil of Veronica not mentioned in the Gospels and adds scenes of the denial of Peter and the repentant thief at Golgotha.

Creating block prints by hand is a way for Yingst to engage with the world and with God. He set up Starving Artist Books in 2005 to publish his own titles, including illustrated editions of the Psalms, a history of blues music, and the writings of Brother Lawrence, using the proceeds to support international charities. His church-sponsored volunteer work with marginalized people in Pensecola, Florida, where he now lives, inspired Glory among the Ruins: The Homeless Project, a portfolio of 15-linocut portraits of homeless men, accompanied by meditations on their life stories.

Yingst believes his slow and tedious artistic method nurtures his contemplative side, keeping him centered and introspective. Before he begins work each morning in a bedroom in his home converted into a studio, he pauses for a devotional time, a connection with God that continues into his art-making, which he views as a form of prayer. He is working on a new book, Everything Could be a Prayer: 100 Portraits of Saints and Mystics, with portrait prints of saints and mystics who developed disciplines for living in isolation relevant to our own time in and out of lockdown. Says Yingst: “I’m studying people who have wrestled with their passions and triumphed with God.”

Nativity

Mother of Mercy

Columba of Iona

Psalm 28

St. Francis Receives the Stigmata

Jesus Carries His Cross

Good Samaritan

That was then, This is now

Dead Batteries

Labor Negotiations

Prayer of John Berchmans

Psalm 54

Psalm 84

Crucifixion

Ecce Homo (Behold the Man)

The Way of the Cross (Title Page)

The Way of the Cross (Station 1)

The Way of the Cross (Station 4)

The Way of the Cross (Station 11)

The Way of the Cross (Resurrection)

The Way of the Cross (Colophon)

Glory Among the Ruins (Title page)