James Janknegt

(born 1953)

James Janknegt is a preeminent painter of parables. At the start of the new millennium he embarked on the ambitious project of coming up with 40 contemporary depictions of Christ’s illustrative stories in the Gospels, one for each day of Lent. The image cycle took over 15 years to complete and was reproduced in the 2017 album, Lenten Meditations, with the artist’s own contemplative texts for the pre-Easter season. In these modern-day makeovers of the New Testament narratives, American Suburbia takes the place of first-century Palestine; flashlights stand in for oil lamps. As Janknegt explains: "Jesus used everyday imagery in his parables, not overt religious symbols. Each generation needs artists who are willing to translate his imagery so that the stories can be 'owned' again."

Born in Austin, Texas, Janknegt attended art school at the University of Texas and with the exception of graduate studies at the University of Iowa with Argentine Printmaker Mauricio Lasansky, he has lived and worked most of his life in the Lone Star State. His eclectic range of job experiences has enriched his visual vocabulary with everyday things. Janknegt has been employed, variously, painting billboards, dressing store windows, driving a taxi, running an off-set printing press, selling tools and plumbing supplies, and managing university buildings. He currently lives at the Brilliant Corners ArtFarm in Elgin, Texas, raising fruit and vegetables with chickens, guinea hens, two dogs and a cat!

Janknegt’s art is embedded in his faith. When he got involved as a teenager in the Jesus Movement of the early 1970s, he painted landscape murals at a “trans-denominational” coffee house. On his return to Austin from Iowa, Janknegt attended an Episcopal Church offering a contemporary mass, where he met his future wife and put his talents to use illustrating liturgical bulletins. In 2005, the Janknegts converted to Roman Catholicism. Since then, he has provided artwork for Liturgy Service Publications, painted cycles on the Rosary and Stations of the Cross, and created murals on Christ as the Water of Life and the Bread of Life for the Sacred Heart Church and Christ the Reconciler retreat center in his home community of Elgin.

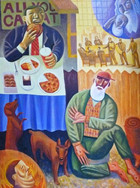

Janknegt says he approaches each biblical narrative “much like a priest would prepare a homily,” giving the scriptural passage a careful read and investigating the cultural context to best translate the meaning into “modern day American vernacular.” In his painting of the parable of The Rich Fool in the Collection, the profit-driven farmer of the Gospels is recast as a greedy property developer, who tears down comfortable family homes—not barns—to build “giant McMansions.” Janknegt borrows a framing device from Eastern Orthodox icons where scenes from a saint’s life surround a central portrait, enclosing his image of the two different households with visual vignettes of doomed neighborhoods and an array of consumer goods from blender to recliner chair.

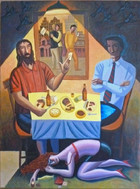

Janknegt came to realize the power of his special artistic vision when a 1985 group show in a downtown Austin bank lobby was cancelled because the Baptist bank president found the artist’s contemporary Crucifixion scene in a shopping mall parking lot to be “sacrilegious.” After that, Janknegt pushed the pedal to the metal in more openly Christian art pieces, critiquing consumer culture in paintings like Merry Xmas, where Mary and the Christ child shelter by a dumpster outside a department store. In The Rich Man and Lazarus, the former is a fast-food glutton and the latter, a street person cadging change, while the day laborers in the Parable of the Vineyard Workers might be migrant grape-pickers in California. In another image in the Collection, Jesus tells the parable of the Two Debtors dressed in a polo shirt, sipping beer with an uptight Pharisee in shirt-and-tie, while a scantily-clad prostitute opens her cosmetic bag to wash his feet.

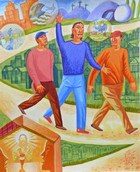

These twice-told tales in modern settings are illuminated theology. In Janknegt’s depiction of the encounter of the Resurrected Christ with two disciples on the Road to Emmaus, the three wayfarers look like campesinos who have stepped out of a wall painting by one of the great Mexican muralists. Their conversation is conveyed in visual vignettes, floating above them like cartoon balloons, depicting three foreshadowings of the Passion of Christ in the Hebrew Scriptures: Abraham sacrificing his son, Isaac; Jonah swallowed by the whale; and Moses lifting up a bronze serpent in the wilderness. The road ends in a gilded shrine, commemorating the evening meal they will share, when the disciples realize in "the breaking of the bread" their fellow traveler is the Risen Christ—anticipating the liturgy of the Eucharist.

Janknegt laments the loss in the modern era of a common language of symbols, which once made it possible to speak about God through images. He aims to overcome our visual illiteracy by creating a new spiritual vocabulary of his own, drawing on his life experiences. Everyday objects are transformed into sacred signs through the stylization of form found in Byzantine iconography and medieval art and the use of multiple perspectives typical of Cubism. Says Janknegt: “I have a sacramental view of the cosmos in which the grand overarching story mingles with my personal stories, beliefs and ideas, and ends up as colors and shapes on a canvas. My painting is autobiographical but infused with the larger narrative of God interrupting time and space."