Raphael Drouart

(1884-1972)

French Art Critic Jean Cassou compared him to a hulking Assyrian sculpture "of the most tender spirit." Dominique Denis, son of the early modern master of sacred artist, Maurice Denis, thought he resembled "a gentle and thoughtful giant, whose absence of body hair made him all the more remarkable." A towering figure of a man, Raphael Drouart was an enigma to his friends, an ardent boxer until nearly 30 years of age, who used his fight-scarred hands to create delicate prints of dancing nymphs, fallen angels, and saints in ecstasy. As Drouart once confessed: "I have no sense of time and don't know in what century I live."

Educated at l'Ecole des Beaux-Arts and the open studio of Painter Fernand Cormon in Paris, Drouart had his most formative aesthetic experience on a visit to Italy in 1910, an artistic "epiphany" while viewing Renaissance Master Sandro Botticelli's painting, Primavera, in Florence. On his return to France, he found his new passion for the visual purity of Quattrocento Italian art was shared by Maurice Denis, his instructor at l'Academie Ranson. Denis took Drouart on in 1912 as his assistant in painting the ceiling of Theatre des Champs Elysees. The printmaker always considered himself as a disciple of Denis, "seduced by [his] decorative sensibility."

On the eve of World War I, Drouart married fellow art student, Alice Rousseau, whose uncle had founded the Ranson Academy. He volunteered for military service in the opening days of the conflict and was captured in fighting at the frontline in Argonne, imprisoned for three and a half years in a German internment camp in Hesse, unable to see the son who had been born in his absence. Drouart made art in a makeshift camp studio, painting scenes of life behind barbed wire. He told Denis in a 1916 letter that he was tempted "to try with all the force of memory to take refuge in a more abstract world."

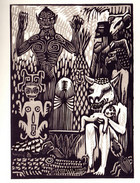

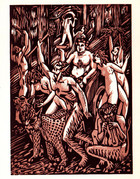

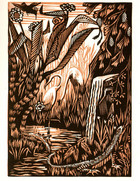

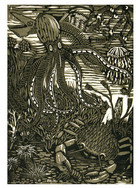

At the end of the war, Drouart took on book illustration work, creating imagery for over 30 literary works during his career. His affinity for abstract worlds and mythological tableaux found full scope in a suite of colored woodcuts for a 1922 edition of French Novelist Gustave Flaubert's dramatic prose poem, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, recounting a hallucinatory night when the desert father struggled with sensual desire and spiritual doubt. Exotic (and erotic) images of pagan gods and Dionysian revels alternate with finely observed studies of the flora and fauna of lush tropical forests and mysterious ocean depths.

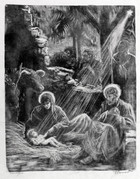

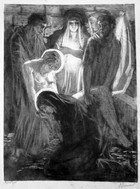

Drouart was a passionate printmaker, experimenting with all forms of the medium from woodcuts to lithographs. He was especially drawn to monotypes, single prints taken of sketches on glass or metal plates. Drouart developed a process of "black smoke etching," which he described as working "from night to light." Sanding a copper plate and blackening it with lamp soot, he wiped clean areas that would appear white in the final print, much as he would with a monotype, smoothing down the surfaces and protecting them with resin for acid baths. The final etched images displayed beautifully modulated passages from black to grey to white without clearly defined boundary lines.

Of the over 500 graphic works Drouart created between 1913 and 1960 more than 75 depict biblical scenes, represented by the sampling of pieces in the Collection. In these religious works, encounters with the divine are signaled by brilliant white, but the artist preferred more nuanced tonal effects that give the impression of mystical visions. Setting his black smoke etchings, The Tears of Jesus and The Holy Women at the Tomb, side by side with his monotypes, The Nativity and The Entombment, we can see how well he succeeded in capturing the spontaneity of these single prints in multiples.

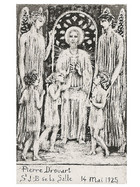

Drouart was a much-acclaimed artist in the interwar period, admitted to the Legion of Honor in 1938. A dedicated family man with little interest in the Parisian art scene, he made prints for relatives and friends, commemorating special occasions like the First Communions of his son, Pierre, in 1925 and his grandson, Alain, in 1953. With the outbreak of World War II in 1940, Drouart retreated with his family to their holiday home on L'Ile-de-Re, an isle in the Bay of Biscay near the seaport of La Rochelle on the west coast of France. He would live there in relative seclusion for most of the remaining years of his life, largely ignored and forgotten in the postwar ascendancy of Modern Art.

The Temptation of Saint Anthony: Title Page

The Temptation of Saint Anthony: Pagan Gods

The Temptation of Saint Anthony: Dionysian Revels

The Temptation of Saint Anthony: Tropical Forest

The Temptation of Saint Anthony: Undersea Life

Saint Veronica II

The Denial of Saint Peter

The Tears of Jesus

The Holy Women at the Tomb

The Nativity

The Entombment

Christ Giving Communion