Charles Plessard

(1897-1972)

The founding of Les Ateliers d’Art Sacre in Paris in 1919 is an overlooked landmark in the history of contemporary religious art. Almost one year to the day after the signing of the armistice ending World War I, French Artists Maurice Denis and Georges Desvallieres launched the Studios of Sacred Art with the bold mission of creating a new kind of religious art for peacetime Europe responsive to contemporary culture and the Roman Catholic faith. The artists and craft workers educated in these workshops would make sacred imagery free of the stultifying realism and saccharine sentimentality of prewar ecclesiastical decoration in building new churches and renovating sacred spaces destroyed in the conflict.

Les Ateliers closed in 1947, never receiving enough commissions to be economically viable, but the aesthetic the movement promoted left its imprint on later generations of religious artists and church art patrons, most notably, Father Marie-Alain Couterier, a Studios associate who enlisted leading secular art-makers of his day like Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, and Pierre Bonnard to decorate modernist-styled sanctuaries like the Church of Notre-Dame de Toute Grace du Plateau d’Assay, completed in 1946. Less well known is Charles Plessard, who can, arguably, be considered the disciple most loyal to Denis and his vision of a new type of religious art, both “traditional and modern,” for use in churches in the postwar era.

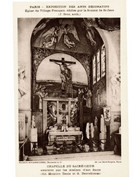

Plessard studied with Denis at Les Ateliers from 1921 to 1925 and worked with his mentor on communal Studios projects like the wall paintings in the Sacred Heart Chapel of the French Village Church at the 1925 Paris Exhibition of Decorative and Industrial Arts and the interior decoration of the Church of St. Louis-a-Vincennes in Paris in 1927. From the mid-1930s onwards, Plessard pursued his own career as a designer of stained glass, accepting commissions over the next three decades at some fifty sacred sites including the St. Martin Church in Ecausseville, Normandy; the Gesu Church in Brussels, Belgium; and the St. Marie-Jeanne Church in Tangiers, Morocco.

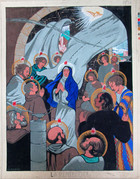

How closely the Studios pupil identified with his former teacher can be seen in a Plessard painting in the Collection of the Annunciation, a theme Denis would explore numerous times in paintings. Just as in the works of his mentor, Plessard avoids strong primary colors, prefering to work in blended, pastel shades. Shapes are defined by the edges of flat color planes and subtly molded forms. All is infused with a soft Italianate light. This work is less about story-telling than creating a visually satisfying impression that enriches the spirit. As Denis, famously, said: “Beauty is an attribute of Divinity.”

Les Ateliers followers believed their refined aesthetic style would be an effective vehicle in promoting Christian teachings and Catholic dogma. In the 1930s, Plessard created a series of large-format gouache paintings as studies for what appears to have been a cycle of instructive posters for catechism classes. The eleven, now in the collection, variously dated from 1933 to 1936, have unfinished captions, roughly blocked in by the artist, and are numbered up to 49 with signatures at the lower right margins with the “nihil obstat” and “imprimatur” approval notations of the Catholic diocesan office. None of these images in reproduction have been found.

The didactic purpose of the sketches is clear in painting No. 22 where captioned, cartoon-like figures of the blessed appear in the sky as Christ proclaims the Beatitudes in his Sermon on the Mount. In image No. 26 on the theme of “the respect for life,” the murder of Abel in the Hebrew Scriptures is grusomely equated with the suicide of Judas in the New Testament. Several of the paintings have color keys. “Gamut no. 1” includes red and blue, highlighting the tongues of fire and the Virgin Mary’s robe in the Pentecost panel (No, 14) and the garments of a Wise Man and the Mother of Christ in the Epiphany sketch (No. 09). "Gamut no. 2 (Annunciation)" with muted pastel hues appears in the sketch of the Baptism of Christ (No. 3)and the scene of Jesus teaching his disciples to pray (No. 23).

Plessard provided color templates and outlined images to be filled in for the 1935 children’s coloring book, Mes Missions a colorier, celebrating the history of Catholic overseas missions. The artist was as careful as he could be about ethnographic detail, but by today’s multi-cultural standards, images of African “amazons” dancing on thorns for the entertainment of a pith-helmeted European missionary are a cringe-worthy reminder of France’s colonial past. (Nor were all young artists up to the task he set them, judging from one unfinished page in our copy of the book!) We do have to admire Plessard’s all-encompassing vision of sacred art, where a coloring book was deemed as worthy of time and effort as a suite of stained glass. It is holistic legacy of Les Ateliers we have lost.

Sacred Heart Chapel in French Village Church

The Annunciation

(No. 49) The Vocation: Christ’s encouter with John the Baptist, Andrew and Simon Peter

Nihil obstat and Imprimatur

(No. 22) Jesus Proclaims a New Law

(No. 26) Respect for Life, your own and others

Color "Gamut" no. 1

(No. 14) Pentecost

(No. 9) Epiphany, Adoration of the Magi

Color "Gamut" no. 2 (Annunciation)

(No. 3) Baptism of Christ, the Holy Trinity

(No. 23) Prayer, Jesus teaches the "Our Father" to his disciples

Mes Missions a colorier (cover image)

Franciscans in China (1342)

St. Francis Solanus in Argentina (c. 1600)

Fr. Francesco Borghero in Dahomey (1861)

St. Francis Xavier in Japan (1550)