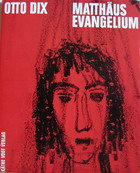

Otto Dix

(1891-1969)

Otto Dix believed artists should have “the courage to depict ugliness.” The German painter and print-maker certainly saw enough of it in a lifetime spanning World War I, the Weimar Republic, the Nazi regime, and World War II. In a ruthlessly expressive, yet realistic style identified with the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement, Dix made art with an unblinking eye out of decomposing corpses in the trenches of the Western Front, sex crime victims in shabby tenements, disfigured war veterans, syphilitic street walkers, and the sexually ambiguous clientele of the Berlin cabaret scene. Denounced by the Nazis as a “degenerate” artist, Dix sought refuge during the war years in the countryside near Lake Constance, painting landscapes.

Dix is remembered today for his shocking studies of the war dead and the sexual decadence of Weimar Germany, dating from the 1920s and ‘30s. Less known are the religious works he created in the later years of his life--over forty studies of the Passion of Christ, alone, in a two year period from 1948 to 1950. Still true to his early artistic vision, Dix wanted to look at the physical sufferings of Jesus “without dissolving in pity.” The caricatured realism of the Weimar works gave way in his sacred art to a more expressionistic style where content was conveyed through strong, repeatedly underscored line work.

Dix drew inspiration from his religious paintings in creating The Mocking of Christ, The Crucifixion, and other sacred images for the suite of 33 lithographs he made for The Gospel of Matthew in 1960 for Berlin Publisher Kaethe Vogt, who was commissioning illustrations for Bible texts from famous contemporary artists. Although Dix was not religious in a traditional way, he was powerfully drawn to the stories of the Bible, especially the Gospel narratives, which he considered “parables of myself and of humankind.” Said Dix: “Christian themes are related to our present just as much as to our past and future.”