Fritz Eichenberg

(1901-1990)

Fritz Eichenberg liked to point out that his German last name meant “oak mountain,” as if this, somehow, explained his extraordinary mastery of the medium of wood engraving. In a creative lifetime dedicated to graphics, Eichenberg occasionally experimented with lithographs and linocuts but always felt most inspired with a graver in hand, creating meticulous white-line prints from wooden panels, preferably, made from endgrain boxwood.

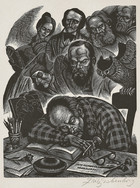

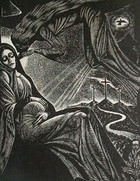

He was a visual artist whose work was inextricably bound up with words in hundreds of illustrations for books and periodicals. In a 1976 self-portrait titled Dream of Reason, the artist sleeps over an open volume, engraving tool in hand, while the ghosts of all the authors whose writings he illustrated--Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Desiderius Erasmus, Charlotte Bronte, Edgar Allen Poe, Leo Tolstoy, Ivan Turgenev--peer expectantly over his shoulder.

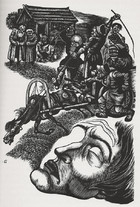

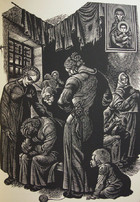

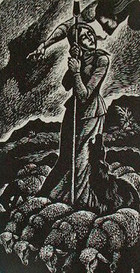

As a student of Russian Literature, I came to know Eichenberg’s art long before I knew anything about the artist, discovering his marvelous prints in the pages of classic 19th Century Russian novels like Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment , The Brothers Karamazov, and The Possessed, or Tolstoy’s Resurrection. Eichenberg had this uncanny ability to pin down the elusive Russian soul in a pictorial style, best described as expressionistic realism. The backgrounds in Eichenberg's illustrations were always full of persuasive period details, yet, the figures seemed wonderfully theatrical and dramatically highlighted. Their faces had the ascetic beauty of icons.

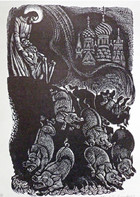

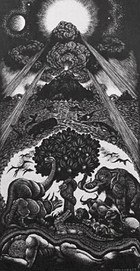

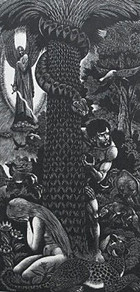

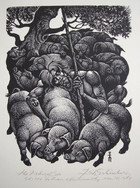

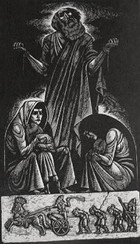

I was not surprised to learn Eichenberg was a man of faith, who described art in sacramental terms as the “outward sign of inward grace.” In 1935, he created a charming image of St. Francis Preaching to the Birds from a high-altitude balloon, printed by the Work Projects Administration (WPA), a U.S. government program, supporting Depression Era artists. In the mid-1950s, he produced a suite of Ten Wood Engravings for the Old Testament. In 1972, he created a folio of prints based on In Praise of Folly, a 16th century satirical work by Christian Humanist Eramus, poking fun at human vanity and corruption in the Medieval Church.

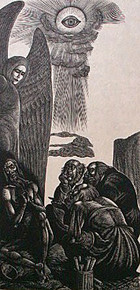

A shared love for Dostoyevsky drew Eichenberg, a German Jewish convert to Quakerism, into a unique creative partnership with Roman Catholic Social Activist Dorothy Day, a meeting of kindred minds, uniting image-making and social conscience in ways, which have immeasurably enriched and democratized contemporary sacred art.

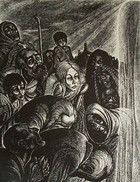

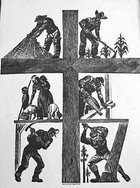

During a forty year period, beginning in 1949, Eichenberg contributed over 100 illustrations to Day’s banner publication, The Catholic Worker, more than fulfilling her hopes that the spirit of the newspaper’s editorial content could be communicated through accompanying images to Day’s friends and supporters who had trouble reading the texts.

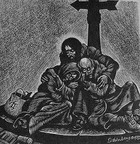

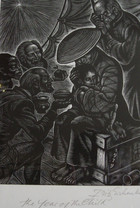

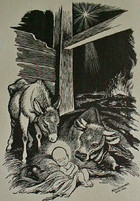

There are three original wood engravings used as Catholic Worker illustrations in my collection, Pieta, The Prodigal Son, and The Year of the Child, as well as a series of print reproductions, including Eichenberg's The Christ of the Breadlines and The Christ of the Homeless. Two iconic images for modern times!

Dream of Reason

Crime & Punishment II

Crime & Punishment I

Brothers Karamazov I

The Brothers Karamazov II

The Possessed

Resurrection I

Resurrection I

Preaching to the Birds (1935)

The First Seven Days

And Their Eyes Were Opened

The Book of Job

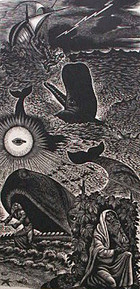

The Book of Jonah

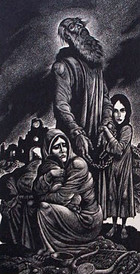

The Lamentations of Jeremiah

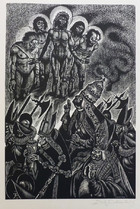

III. The Follies of Worshipping Idols

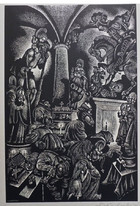

VI: The Follies of the Monks

IX: The Follies of the Popes

Pieta

The Prodigal Son

The Year of the Child

The Light (1940)

The Christ of the Breadlines (1950)

Nativity (1950)

The Lord's Supper (1951)

The Long Loneliness (1952)

Joan of Arc (1953)

The Labor Cross (1954)

The Lamentations of Jeremiah (1960)

The Black Crucifixion (1963)

Sermon to the Birds (1964)

Isaiah 11 (1976)