Charalambos Epaminonda

As you follow the winding road from Pafos to the resort city of Polis on the Northwestern coast of the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, keep your eyes open for something a bit out of the ordinary, when approaching the village of Stroumbi. A quaint figure in bas-relief, decked with vine garlands, extends visitors a cup of wine from a welcome sign at the edge of town, while other multi-layered murals further along the highway display delightful vistas of village life and vineyards, peopled with saints and mythological figures.

They are the work of Resident Artist Charalambos Epaminonda, who also writes and illustrates children’s books and takes on icon commissions, building a little jewel of a Greek Orthodox chapel in his spare time on a hill above his home, a dwelling place every bit as whimsical as the fantastic Byzantine structures in his drawings. Amid all these varied artistic activities, Charalambos remains calm and centered, a man at peace with himself, and a paradigm of a spiritually-centered artist, indifferent to commercial success or critical acclaim.

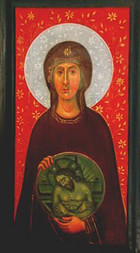

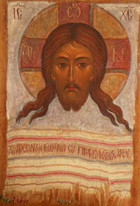

Compared with much traditional Orthodox iconography, the work of Epaminonda exudes warmth and humanity, revitalizing old pattern-book imagery in visually exciting ways. Just the added touch of a floral pattern to the red background of his Virgin of the Sign underscores the maternal, caring side of this grieving Mary, who offers up her dying son to the World. His Christ Made Without Hands is actually painted on a woven cloth, suggesting the towel on which Christ left an imprint of his face to heal the ailing King of Edessa, according to the traditional Eastern Orthodox story of how this miraculous image came into being.

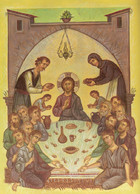

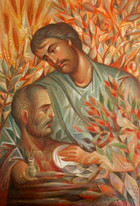

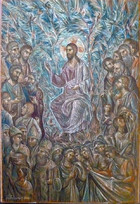

A longtime friend of the Collection, Epaminonda took on the commission of creating an iconographic triptych based of three "parables of mercy" from the Gospel of Luke, the Prodigal Son, the Sower and the Seed, and the Good Samaritan. The trio of separate paintings are united in composition and color palette with Christ depicted in the center panel, scattering the good seed of the Gospel. Trained in both art and theology, the normally reticent artist spoke eloquently of what holds the triptych together--the notion of epistrophi, a Greek word, meaning “coming back,” “returning,” and in its New Testament variant, “conversion.”

Not only are humans reconciled one with another in these wonderful images, but the whole created order, animate and inanimate, vibrates with divine energy. The schema is repeated in the painting, Madonna of the Woods. Like shifting shapes in a kaleidoscopic picture puzzle, the central figures of the Virgin Mary and the Baby Jesus are almost indistinguishable from the fragmented, multi-colored background with fish and bird in wind-stirred forest and flowing water, reflecting the artist’s concept of “Deep Incarnation,” the belief that God brought redemption not only to humanity but all of creation.

Epaminonda's artistic innovations have not always been welcome in conservative Cypriot church circles. To give the artist a free hand to develop his new style, the Collection launched him in 2016 on a multi-year project to create a cycle of contemporary icons on the Life of Christ. The first completed work in the series, depicting the Agony in the Garden, challenges the iconographic convention of presenting holy figures in static poses against symbolic landscapes in a dynamic scene formed from cubistic shards of color. While events unfold in human history, the surrounding world of nature bends and sways in anguish over the ordeal of Christ. It is a promising glimpse of things to come as the artist adds more scenes for the Gospel to the image cycle!

The Virgin of the Sign

Christ Made Without Hands

The Prodigal Son

The Sower & the Seed

The Good Samaritan

Madonna of the Woods

The Birth of Christ

The Virgin and Child

The Birth of Christ

Flight into Egypt

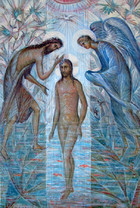

Baptism of Christ

"Consider the Lilies"

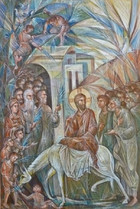

The Triumphal Entry

The Agony in the Garden

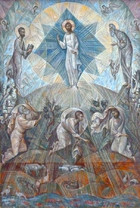

The Transfiguration

The Risen Christ Encounters the Two Marys

The Supper at Emmaus

Jesus and Doubting Thomas

Together With Grandma

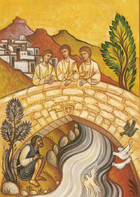

Encounter at the Bridge

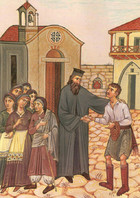

In the Village Square