Howard Finster

(1916-2001)

Howard Finster is one “outsider” artist who sure found his way to the inside track! A Revivalist Baptist Minister with a six-grade education from the south end of the Appalachians, Finster exchanged pulpit-pounding for painting at the age of sixty and soon became a favorite of the art world and mass media. He was featured in publications like the Wall Street Journal and Rolling Stone, interviewed on The Johnny Carson Show and Good Morning America, and commissioned by the rock groups R.E.M. and Talking Heads to design album covers. The Coca-Cola Company even asked him to make an eight-foot high version of its iconic bottle for the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Finster never let his cult status go to his head. He said he was simply “God’s instrument…just like this paint brush I’m holding in my hand is my instrument.”

Finster was a prolific artist, who splashed paint on whatever he could lay his hands on (gourds, bottles, mirrors, irons, snow shovels, trash cans, even an old Cadillac!) working, mostly, on canvas, panel, or wooden cut-outs. Finster set out to make 5,000 works of art and carefully numbered his creations, including the date and, often, the exact time he finished them. At his death, he left behind over 46,000 pieces! The self-taught artist wanted, most of all, to be remembered for Paradise Gardens, the outdoor “installation” he created from art pieces and found objects on reclaimed swampland by his home in Pennville, Georgia. Sadly, the three-acre complex awaits restoration, many of its treasures, carted away by avid collectors.

Finster believed he had received a direct call from God to make art. He loved to talk about the moment in his workshop in 1976, when he was touching up a bicycle frame with white paint and saw a face in a smudge on his finger tip. A warm sensation came over him, and he heard a voice telling him to “paint sacred art!” When Finster protested that he had no talent, the voice replied: “How do you know?” He took a dollar from his wallet, taped it to a plywood board, and sketched a portrait of George Washington. There was no stopping him after that.

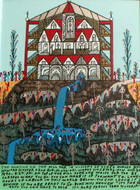

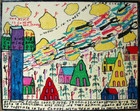

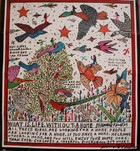

Finster was something of a William Blake. He remembered having his first glimpse of heavenly realms at the age of three and considered himself “a stranger from another world,” dispatched to earth on a special mission. Said Finster: “God sent me here to preach his Word in the Last Days and to be a Man of Visions.” Finster’s art abounds with scenes of the End of Time, the Great Rapture, and heavenly realms with fantastic, multi-tiered mansions, teeming with brightly-colored angelic beings. The Mansion on the Hilltop, Visions of Other Worlds, and The Lord is Coming Back are typical of this genre of visionary, apocalyptic art.

As delightful as these glimpses of celestial kingdoms may be, I find I am most drawn to the astonishing verbal content of Finster’s work, perhaps, because, like the artist, I come from a Christian tradition, where expounding the Word left little room for images. For Finster, a picture is a thousand words--and, then, some!

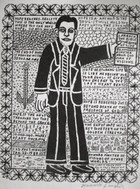

The lithographic copy The Devil’s Vice, depicting a hapless sinner trapped in a vice, is really a patchwork quilt of scrawled spiritual admonitions, biographical notes, rhymed verse, and pithy aphorisms (all in Finster’s idiosyncratic grammar!) One comment reads: “I am 70 years old. Never been drunk yet. How about you?” The Preacher Man is a sermon about hope, where the artist tells us: "Hope of eturnal life is like medecine for your soul." He was particularly proud of finding ways to incorporate 26 verses into the Talking Heads album cover. His art gives a whole new meaning to the Bible passage, “be ye doers of the word, and not hearers, only. (James 1:22, KJV)!"

The Mansion on the Hilltop

Visions of Other Worlds

The Lord is Coming Back

The Devil's Vice

The Preacher Man

Jesus

The Last Supper

Habitat for Humanity

The Angel

The Angel

Heaven & Earth Shall Pass Away

Heaven & Earth Shall Pass Away

Heaven & Earth Shall Pass Away

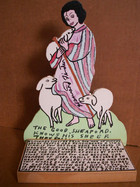

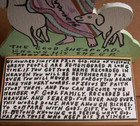

The Good Shepherd

The Good Shepherd

The Good Shepherd

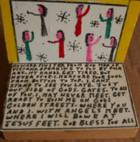

Tower of Angels

Tower of Angels