Eric Gill

(1882 -1940)

English Artist Eric Gill cut an odd figure in the world of sacred art in his belted, mid-calf craftsman’s smock and knee socks, worn day-in, day-out, regardless of the weather. The son of a Non-Conformist parson and the grandson of a missionary to the South Seas, Gill inherited a penchant for pulpit-pounding, turning out countless books, pamphlets, and letters to editors, touching on everything from disarmament to the problems of wearing pants and the proper way to make custard.

In a effort to create “a cell of good living in the chaos of the world,” Gill tried three times to found artistic communes in England and Wales, where, with family and followers, he could realize the ideals of the late 19th Century Arts and Crafts movement, living where he worked and making what he needed. Gill hoped to combine the Victorian values of a well-ordered hearth and home with a Roman Catholic faith, embraced with all the fervor of the convert, to find a way of living where “it all goes together.”

It never did for Gill. Like his great near-contemporary, Stanley Spencer, he struggled all his life to reconcile flesh and spirit, trying one way or another to justify his voracious sexual appetites as an expression of Divine Love. His frankly erotic illustrations of nude couples in “spiritual” works like The Song of Songs and Procreant Hymn caused unease in the church hierarchy, which had once embraced Gill as a role model for contemporary Catholic artists.

Gill defended his art in a pithy aphorism: “There is no such thing as impropriety, when it comes to saving souls.” Few of his co-religionists saw it that way. The issue of whether Gill should even be considered a Catholic artist has been further fueled in recent years by biographies, suggesting Gill ran his communities more along the lines of an oriental harem than a quasi-medieval monastery and had sexual relations with his teenaged daughters.

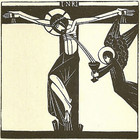

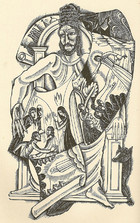

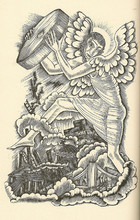

I leave the decision to others, whether to take the chisel to his stylized bas-reliefs of the Stations of the Cross in London’s neo-Byzantine Westminster Cathedral. Gill began work on the limestone panels in 1914, completing them in time for their Good Friday dedication in 1918. He reproduced the images in a series of wood engravings for a 1917 devotional book, The Way of the Cross. Seven of these prints can be seen, here, from the 1929 Douglas Cleverdon edition of Gill's graphic works, along with a larger format wood engraving of Station I, Christ Before Pilate, dating from 1921.

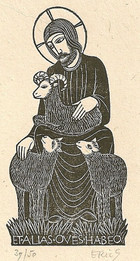

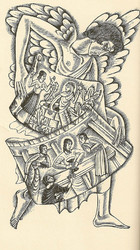

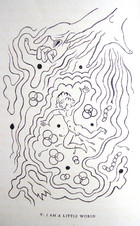

Gill was a master of the highly demanding art of wood engraving. The two versions of Christ, driving the Money Changers out of the Temple, (a favorite theme of the anti-capitalist Gill!) and The Good Shepherd (1926) in my collection are excellent examples of white line prints, where the paper picks up ink applied to the uncut surface of the wood block to form a negative image. The Holy Sonnets of John Donne illustrations are representative of Gill's black-line prints, where the image is made from ink deposited on raised lines.

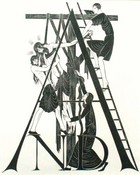

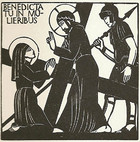

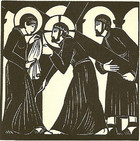

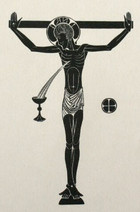

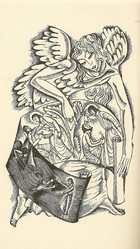

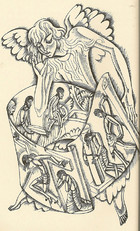

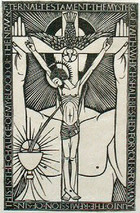

Gill is best remembered nowadays for his Gill Sans-serif typeface. In The Trinity With Chalice, he combines word with image, using lettering as a integral visual element. Gill's text art masterpiece is The Four Gospels of the Lord Jesus Christ, printed in 1931 by the Golden Cockerel Press, a small English publishing house, famed for its handmade books. Gill created the typeface and illustrations for the King James Version text. In the style of medieval manuscript illuminators, he turned chapter and verse headings into decorated, multi-figured compositions. You can view four examples of these text art wood engravings from the 1934 Faber edition of Gill prints in the image gallery.

Station I (1921)

Station III

Station IV

Station VI

Station IX

Station X

Station XII

Station XIV

The Lamb Has Redeemed the Sheep

Christ & the Money Changers I (1919)

Christ & the Money Changers II (1919)

The Good Shepherd (1926)

Epiphany

Crucifix, Chalice, & Host

The Carrying of the Cross

The Ascension

The Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Mark

The Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of John

The Acts of the Apostles

The Revelation

Thou Hast Made Me

I am a Little World

At the Round Earth's Imagin'd Corners

Death Be Not Proud

The Trinity with Chalice (1914)

"And it came to pass..." (Matthew 26)

"In the end of the sabbath..." (Matthew 28)

Matthew 27:27