Alfred Manessier

(1911-1993)

Alfred Manessier holds a special place in the Sacred Art Pilgrim collection as a leading exponent of non-figurative religious art. Representational pieces--like his color lithograph of the nails of Christ's Passion on view here--are rarely found in his work. But even when Manessier's images are pure abstractions, they are seldom simply exercises in composition and color, referring to nothing beyond their immediate surface like many pieces of modern art. His expressive forms evoke the essence of landscapes and the forces of nature, current events, the central narratives of the Christian faith, mystical writings, even Bach compositions.

Manessier cared about meaning. He had undergone a life-transforming religious conversion in 1943, while on retreat at a Trappist monastery, and considered art-making “an act of hope and love…a way of living through events, using a form of expression which avoids indifference and despair.” Titles were important to Manessier and all too often ignored by modern art dealers, who seem to think generically-labeled prints (especially when the subject might just be religious or political!) are more attractive to buyers, looking for something to hang on their office walls.

What room for reflection opened up for me, when I discovered the lithograph sold to me as Composition in Yellow and Black was really the fifth plate in a suite of Easter prints and depicted the entombment of Christ (La Mise au tombeau (Plate V))! A lithograph identified, simply, as Composition, proved to be Proces de Burgos II, a work expressing the artist’s outrage at the death sentences handed down to Basque nationalists at a controversial trial in Burgos in Franco Era Spain.

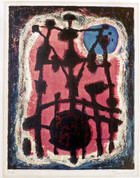

Guided by verbal markers provided by Manessier, you can mine the many layers of meaning in his abstract art. Take a closer look at the lithograph titled, Gethsemani, depicting Christ's time of prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane. It seems to vibrate with a visual tension, created by the central machine-like, bluish-black form juxtaposed against a background grid of reds and mauves. Or consider the triptych, illustrating Senegalese Poet Leopold Sedar Senghor’s Elegie pour Martin Luther King. In this reflection on the assassination of Martin Luther King, vertical black crosses in various shades of blue and tan in the Left Panel and Right Panel frame the chaotic, tilted, black and red-spattered mass of the Central Panel. Your own subjective interpretations of these powerful images are as valid as mine.

Manessier’s lithographs for Les Cantiques Spirituels de saint Juan de la Croix (1957-58) come as close as any work of art can to expressing the spiritual ecstasy, described in the poetry of the 16th century Spanish Mystic, St. John of the Cross. The artist selected 12 stanzas of verse for illustration, which capture the various states of the soul in its movement toward God. Plate III depicts the waiting soul, veiled in the obscurity of night, with muted blue and purple tones, bounded in a black, vertical grid. Plate IV and Plate VII show chaotic shards or swirling liquid forms, exploding from fiery orange backgrounds, beautifully evoking the wounding of the soul by divine love and its kindling with holy fire. Strong, black verticals reappear in Plate XI to direct and channel the flow of repeating shapes and colors, illustrating the celestial harmonies of the soul in union with God. Manessier spoke of “eliminating the figurative, searching to find the equivalent of music in painting.” He has, certainly, achieved this, here.

Manessier’s non-figurative style of sacred art, probably, found its fullest expression in the cycles of stained glass he created for numerous churches across Europe. He had a special love for the ancient windows of Chartres Cathedral and the surrounding region of Beauce, where he kept a studio from 1956 onwards. In 1963-1964, Manessier transcribed and illustrated the text of Presentation de la Beauce a Notre-Dame de Chartres, an impressionistic poem by the late 19th Century French Essayist Charles Peguy, describing a pilgrimage by the faithful of the Beauce region to the shrine of Our Lady of Chartres. Using a limited palette of blue, red, mauve, tan, brown and ochre, Manessier suggests the repetitive, incantatory phrasing of Peguy’s poetry in elongated, frieze-like drawings, twisting and turning like pilgrim pathways across the manuscript’s 65 folio pages. In Page 28 and Page 36 words in calligraphy not only serve as bearers of meaning but as decorative elements in the artist’s overall composition.

Few themes had such resonance for Manessier as the Easter narrative of Christ’s death and resurrection. So, it is, probably, no coincidence that his most productive period of print-making was framed by two cycles of Passion imagery, one series of seven lithographs, dating from 1949 (represented, here, by Les Tenebres (Plate IV) and La Mise au tombeau (Plate V)) and a second suite of 15 lithographs, made almost thirty years later, six of which can be seen in this gallery. Comparing his 1949 entombment print with one, depicting the guard at the tomb (La Garde au tombeau plate XI) from the later series or his 1958 study, Gethsemani, with similarly-themed Le Jardin des oliviers (Plate I) from the 1978 suite, you can see how Manessier’s later lithographs have gained in expressive power as he became more fluid in his mark-making. There are somber tones in plenty throughout the 1978 Easter suite, but we see shades of blue, green, red and orange mingling and bleeding through his dramatic black line work. His resurrection scene in L'Apparition a Marie de Magdala (Plate XV) is a truly joyous riot of color.

Manessier added light to his artistic tool box, when he accepted a commission in 1948 from a rural 17th century church in the Eastern French commune of Les Breseux to create stained glass windows in a contemporary style, a broadening of his artistic horizons that culminated in a luminous cycle of modernist windows for the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Northern French town of Abbeville, completed just months before his tragic death in an automobile accident. A 1979 lithograph with black outlined color planes in a grid-like composition recreates his work in this sacred art medium. In an era when contemporary art was dominated by images of despair, Manessier wanted his paintings, prints, tapestries, and windows to move viewers, as he once phrased it, beyond “the Passions” to “the Great Hallelujahs.”

The Three Nails

Proces de Burgos I

Gethsemani

Elegie pour Martin Luther King (Left Panel)

Elegie pour Martin Luther King (Central Panel)

Elegie pour Martin Luther King (Right Panel)

Les Cantiques spirituels (Plate III)

Les Cantiques spirituels (Plate IV)

Les Cantiques Spirituels (Plate VII)

Les Cantiques spirituels (Plate XI)

Presentation de la Beauce (Page 28)

Presentation de la Beauce (Page 36)

Presentation de la Beauce (Book Jacket)

Les Tenebres (Plate IV)

La Mise au tombeau (Plate V)

Les Jardin des oliviers (Plate I)

L'Emprisonnement (Plate III)

Le Crucifiement (Plate IX)

Le Sang et l’eau

La Garde du tombeau (Plate XII)

L'Apparition a Marie de Magdala