Georges Rouault

(1871-1958)

The Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection all began with one painting by Georges Rouault. discovered on the website of a London art gallery in a random internet search of Christ imagery. Numerous religious art objects had come my way, mostly picked up as travel souvenirs, but after encountering Rouault’s Christ et docteur on-line I took the plunge into serious art collecting. The oil on paper mounted on canvas study of Christ and a Pharisee vividly captured for me the secret nighttime meeting of Jesus and Nicodemus recorded in the third chapter of the Gospel of John. In Rouault’s rendering of the scene, you see the somber, ascetic Christ extending an all-embracing arm in love toward the worldly-wise, doubting doctor of the law. Only Rembrandt could equal this!

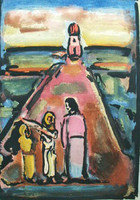

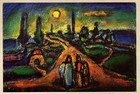

I was able to acquire a second masterpiece from the Rouault family collection at the One Hundred Masterworks of Georges Rouault exhibition at the Galerie Tamenaga in Paris, marking the 150th anniversary of the artist' birth. Paysage biblique (recontre) depicts the meeting of Mary Magdalene and the Risen Christ outside the garden tomb on Easter morning in an oil, ink, and gouache painting on paper mounted on canvas that Rouault worked on between 1939 and 1945. It is rendered in his distinctive abstract figurative style with passages of blue, aquamarine, carmine, gray, and yellow, outlined in black, suggesting panels in a stained glass window.

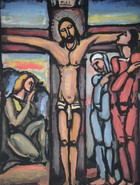

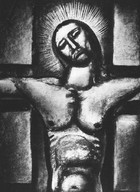

To my mind, Rouault is the unrivaled master of contemporary sacred art. From his early claustrophobic, deep sea-colored portraits of prostitutes through his rich grey-black graphic studies in suffering and atonement to his later paint-crusted, jewel-toned biblical landscapes like Paysage biblique, his artistic career traces a moving and humane trajectory from despair to redemption unequaled in the modern era. His numerous studies, alone, of the Crucifixion, including Christ en croix (1925), Christ en croix (1932), and Christ en croix (1936) in the Collection are a treasure trove of contemplative riches.

Born in a basement in a working class district of Paris during the Communard Uprising of 1871, Rouault was apprenticed as a teenager to a stained-glass workshop. He achieved early success, working in the style of his art teacher and mentor French Symbolist Gustave Moreau, but a dramatic shift toward brutally-rendered expressionistic views of Parisian lowlife in 1904 left one-time admirers shocked. Roman Catholic Social Realist Writer Leon Bloy denounced what he termed Rouault’s “leap into utter darkness." The artist had embarked on the solitary road he would follow to the end of his life. Images of vagabonds, wayfarers, and Christ with nowhere to lay his head would be oft-repeated motifs in his work.

Rouault’s style of art-making defies conventional labeling. He cannot be conveniently classified as a Post-Impressionist or a Fauvist or an Expressionist, though there are, certainly, elements from all these art movements to be seen in his work. When most of his contemporaries embraced abstract art, Rouault remained, stubbornly, figurative in his compositions, even if what he depicts is more true than real. In an age when artists were fleeing the church in droves, Rouault‘s religious faith only deepened. "My only ambition. " he said, "is to be able some day to paint a Christ so moving that those who see Him will be converted." Poet Andre Suares, his friend and artistic collaborater, described Rouault as "the monk of modern art."

The artist's religious beliefs drew much from the writings of the 17th Century French Philosopher Blaise Pascal. He kept a copy of Pascal's Pensees alongside the Bible on his nightstand, incorporated quotations from Pascal into his art, and provided two illustrations of the Passion of Christ for Avec Pascal, an essay-portrait of the great French thinker by Literary Critic Marcel Arland, published in 1946. Rouault, like Pascal, saw reality etched in dark tones, "an anguised world of shadows and pretences." He believed the greatness of humanity in its fallen state came by emulating Christ in the acceptance of redemptive suffering. As he once wrote, "I carry within myself an indefinite depth of suffering and melancholy which life has only served to develop and of which my painting, if God allows it, will be the flowering and imperfect expression."

In 1917, Avant-garde Art Impresario Ambroise Vollard added Rouault to his stable of promising modernists, which included Picasso and Matisse. Their patron-artist relationship was never an easy one and ended in a landmark 1947 court decision, affirming the artist’s right to ownership of his own work, against the claims of Vollard‘s heirs. The collaboration did result in a splendid series of fine art suites in which Rouault extended the boundaries of modern graphics, including the Miserere portfolio, commisioned in 1916 and published in 1948; Passion, a series of illustrated meditations by Suares on the death of Christ, printed in 1939; and an edition of French Poet Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal , produced after Rouault’s death in 1966.

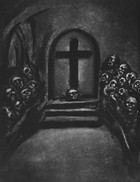

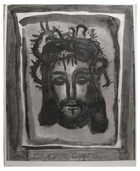

Originally conceived as a two-volume work on the themes of mercy and war with fifty prints in each section, Miserere was finally published with 58 mixed media prints. Rouault transferred painted sketches to metal plates, combining the techniques of aquatint, drypoint, etching and engraving to enhance his tonal range of greys and blacks. The focus of the portfolio is Christocentric, opening with a print plate of Christ humiliated and a plea for mercy from Psalm 51 and ending with a thorn-crowned portrait of Christ, invoking the Song of the Suffering Servant in Isaiah 53. Images of suffering humanity are linked throughout the suite to the suffering of Christ, underscored in a print of the Crucifixion with the quotation from Pascal: “Jesus will be in agony, even until the end of the world.” Hope of the Resurrection is symbolized by a cross in the central niche of a charnel house heaped with skulls.

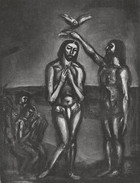

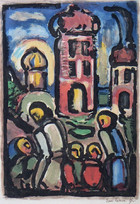

Rouault created 99 prints to accompany the text of Passion, a series of reflections on events surrounding the Crucifixion by his friend, Suares. Seventeen (a frontispiece and 16 plates) are full color renderings of monochrome Rouault etchings (both variations are on view in the gallery) plus 82 wood engravings cut by Georges Aubert from Rouault designs. The tinted versions of the Passion prints by Roger Lacourier, carefully overseen by Rouault, follow a color key of richly layered hues, suggesting the stained glass of his early career with their heavy black framing lines. These images are not so much illustrations but evocative pieces on the Passion, where Christ passes through bleak industrial suburbs and barren landscapes, encountering the poor, the needy, wayfarers, pilgrims, and children on his way to Golgotha. Cross bearing is a central theme, both in traditional depictions of Christ on the Way of Sorrow and in three color plates of peasants weighted down with timber, perhaps, the cross beams of future crucifixions.

The prolific print-maker published the portfolio, Stella Vespertina, in 1947 with 12 high-end heliogravures of original gouache and oil sketches. As always, Rouault pushed the limits of graphic art by mixing techniques to enrich the quality of the reproductions, sometimes making changes by hand directly on the photographic plates. The theme of the evening star is reflected in four scenes of sunset and moon rise. We catch glimpses, once again, of fellow-travelers on the road. Rouault reflected on his life as an artist in a lengthy preface to the print collection, composed in the paradoxical, aphoristic style of Pascal’s Pensees. “The conscience of an artist worthy of the name,” wrote Rouault, “is like an incurable leprosy, which causes him infinite torment but sometimes fills him with silent joy.”

Rouault was one of those rare artists who achieved success in his lifetime. A 1947 monograph from the Modern Art Museum in New York concluded that “in relation to other living artists, [Rouault] emerges as one of the few major figures in 20th century art.” What Rouault once called his “outrageous lyricism” was soon scorned by the advocates of Abstract Expressionism, who came to control the art world in the 1950s-1960s. His undiluted sacred imagery does not seem to suit sardonic, post-modern tastes, either. Not a single one of Rouault’s canvases now hangs on the walls of the new MoMA. Major exhibitions commemorating the anniversaries of his birth and death like the Galerie Tamenaga show give some hope for the future rehabilitation of this grievously neglected modern master.

Self-Portrait

Christ et docteur

Paysage biblique (rencontre)

Paysage biblique

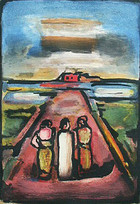

Paysage anime

Christ en croix (1925)

Christ en croix (1932)

Christ en croix (1936)

Christ Humiliated (Frontispiece)

Christ Crucified (Text Insert)

Miserere (Plate I)

Miserere (Plate XXVIII)

Miserere (Plate XXX)

Miserere (Plate XXXV)

Miserere (Plate LVII)

Miserere (Plate LVIII)

Passion Exhibition Poster

Christ aux portes de la ville (Frontispiece)

Christ au faubourg (Plate I)

Christ au faubourg

Chemineau (Plate II)

Christ et les enfants (Plate V)

Christ et les enfants

Ecce Homo (Plate VI)

Le Viel Homme Chemineau (Plate VII)

Ecce Dolor (Plate VIII)

Christ et les pilgrimes (Plate XIII)

Les Disciples (Plate XV)

Aide-Bourreau (Plate XVI)

From "Tete a tete"

From "Calvaire des athees"

From "Calvaire des athees"

From "Il revoit le Thabor"

From "C. Pontius Pilatus Propraet"

From "Disciples"

Christ aux bras leves (Plate II)

Christ de face (Plate III)

Nocturne (Plate VII)

Coucher de soleil (Plate IX)

Crepuscule (Plate X)