Warner Sallman

(1892-1968)

Warner Sallman’s Head of Christ is, without doubt, the best known image of Jesus on the planet. Since the portrait first appeared in 1940, it has been reproduced around the world as often as a 500 million times on wall plaques, calendars, church bulletins, post cards, greeting cards, funeral cards, bookmarkers, book covers, coffee mugs, commemorative plates, clocks, lamps, embroidery patterns, T-shirts--on seemingly any surface, taking a printed picture!

You can say what you like about the painting as a painting, but there is no denying the extraordinary popular appeal of this image or the stupendous success of the marketing strategy behind it, so peculiarly American in its mix of genuine piety and blatant commercialism. (For readers who want to examine the phenomenon in more detail see Icons of American Protestantism: The Art of Warner Sallman, Edited by David Morgan, Yale University Press, 1996.)

It’s hard for me to view this image with any kind of objectivity. The Sallman portrait of Christ, in theme and variations, has accompanied me all through my life. It was the sacred image I knew best as a child, attending Baptist Church Sunday School in suburban Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the 1950s. A cherished piece of family memorabilia is a faded card with the image and a few lines of poetry, once tacked up on the wall of my grandmother’s bedroom.

My tastes in sacred art have, certainly, changed in 50 years, but the iconic power of Head of Christ still resonates for me, when seen in contemporary works like Tyrus Clutter's Head of Christ or the Crucifix by New Mexican Mixed Media Artist Nance Lopez--even when it's graffiti-covered in a whimsical piece of "outsider art", which I've dubbed the Hippy Head of Christ.

As befits a true icon, the story of how Sallman created his famous image has supernatural elements. A Chicago-based commercial artist and committed Christian, Sallman was working on a new portrait of Jesus for the February 1924 edition of the Covenant Companion, the monthly magazine of his denomination, the Evangelical Covenant Church. With a deadline looming the next day, Sallman could not come up with just the image he wanted and went to bed in despair. He awoke in the early hours of the morning to see a vision of Christ, which would serve as a prototype for the charcoal drawing, Son of Man (1924).

Sceptics are quick to point out the remarkable similarity of this first Sallman sketch to the Christ in French Artist Leon August L’hermitte’s popular 1892 painting, Friend of the Lowly. Whatever the source, Sallman went on to develop the portrait in innovative ways. Drawing on his experience in advertising, he created a thoroughly modern Christ, seen in three-quarter profile, complete with theatrical highlights more akin to Hollywood publicity shots or studio-posed photographs. Sallman also recognized the “ecumenical” potential of his work, adding a halo so his Son of Man would appeal to a Roman Catholic market.

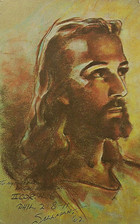

Sallman’s big breakthrough came in 1940, when Publishers Anthony Kriebel and Fred Bates encouraged him to rework his earlier portraits into a luminous, oil painted version, his famous Head of Christ. It soon became the standard for all Sallman’s later studies of Jesus. Millions of pocket-sized reproductions of the image were distributed by the Salvation Army and the YMCA to American soldiers in World War II. Sallman would redraw this special portrait, at least, 500 times before live audiences in evangelistic “chalk-talks” across the country, like the one held at the First Methodist Church of Mason, Iowa in 1962, commemorated in a post card.

Guided by Kriebel and Bates, Sallman carried out a revolution in mass-market American religious imagery in the 1940s and 1950s, replacing widely-circulated reproductions of famous 19th century works of sacred art, like Briton William Holman Hunt’s Light of the World, German Bernard Plockhurst’s The Good Shepherd, German Heinrich Hofmann’s Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, and Swiss Artist Robert Zund's The Road to Emmaus with his own, modern re-workings of these popular themes, Christ at the Heart's Door, The Lord is My Shepherd, Jesus in Gethsemane, and The Road to Emmaus. Jesus’s eyes may be lowered or raised toward heaven, the head may be turned more to the left or to the right, but in every case these portraits are near exact reproductions of his already classic 1940 Head of Christ.

Times and tastes change, and Sallman found less favor with Christian art “consumers” in the Swinging Sixties and 1970s. In an era of dramatic social change, when race and gender were hot topics, his 1940 Head of Christ looked a bit too North European, too effeminate, and too dated with his delicately chiseled features and carefully waved hair. In 1964, Concordia Publishing House came out with a rival Head of Christ by Artist Richard Hook, depicting a swarthy, virile, and uncombed Christ, designed to appeal to young people in the Jesus Movement.

Two years later, Sallman unveiled his last Portrait of Jesus. As in Hook’s Head of Christ, Sallman’s Savior looks the viewer straight in the eye. Otherwise, it’s really the same, gentle Jesus of the 1940 study. Sallman must surely have realized his presentation of the caring side of Christ was the real attraction in all his portraits. Time has proved him right. Reproductions of the Head of Christ are just as popular in this new millennium as ever.

Sallman’s sacred art seems to be riding a wave of nostalgia among Baby-Boomers, like me, who are avid collectors of vintage Sallman prints. Perhaps, we want to remember our childhood through images like The Boy Christ, He Careth for You, and Christ Our Pilot as a place of peace and security, comfort and consolation, when we knew with innocent, absolute certainty what a friend we had in Jesus.

Head of Christ

Jesus Never Fails Plaque

Head of Christ Card

Head of Christ

Crucifix

Hippy Head of Christ

Detail of Christ from heliogravure of Friend of the Lowly

Son of Man (1924)

Son of Man (1935)

Son of Man (1937)

Head of Christ (1962)

The Light of the World

Christ at the Heart's Door

The Good Shepherd

The Lord is My Shepherd

Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane

Jesus in Gethsemane

The Road to Emmaus

The Road to Emmaus

Head of Christ

Portrait of Jesus

The Boy Christ

He Careth for You