Sadao Watanabe

(1913-1996)

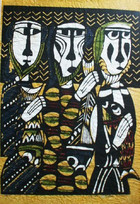

Famous for traditional ukiyo-e “floating world” wood-cuts of Mt. Fuji landscapes, grimacing actors, and graceful kimono-clad courtesans, Japan would not be the first place you would expect to find good biblical art prints. Yet, this nation, where less than 2% of the population is nominally Christian, has given the sacred art world one of the most talented Bible story-tellers of the 20th century, Stencil Printmaker Sadao Watanabe. Although Watanabe was originally repulsed by what he called the foreign “smell of butter,” associated with Japan’s Christian community, he eventually found his way to the Church, after a miraculous recovery from tuberculosis, and dedicated his life to discovering artistic ways of “expressing Christianity within a Japanese context.”

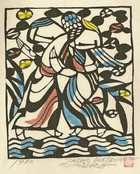

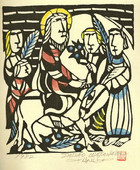

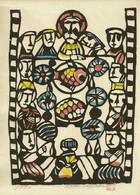

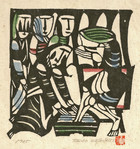

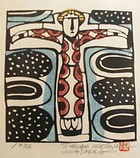

Trained as a textile-dyer, Watanabe was inspired by the mingei (folk art) movement of the 1920s-1930s to produce prints on paper, using katazome, a paste and stencil technique for coloring kimonos from the Okinawa Islands. Watanabe would make a drawing, first, on tracing paper, using a knife to cut a stencil of the design out of hardened paper. Putting the stencil on a light box, he placed the print sheet on top, painting in all the areas he wanted to color inside the silhouette of his pattern. Next, the stencil would be placed atop the colored page and covered with a silk screen. Using a wooden spatula, Watanabe spread a resist paste, covering over all the colored areas of the print. He removed the stencil, painting the exposed stencil lines and the covered areas in black. Finally, the paste coating was washed off in a water bath to reveal the colors within the black stencil lines.

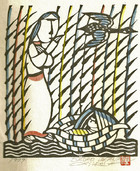

Working with his wife, Watanabe was able to produce as many as 200 prints from a single stencil. In keeping with the principles of the mingei movement, only organic materials were used in preparing colors with soybean milk as the binder. Watanabe printed his images on handmade kozo (mulberry) paper in two formats. He created small, intricately patterned biblical scenes on untreated paper sheets, known, simply, as washi (Japanese paper). Watanabe also made large, folio-sized momigami (wrinkled paper) prints. Their coarsely textured surface, which suggests medieval manuscript pages, was made by wrinkling and stretching specially strengthened sheets of kozo paper, tinted in bright colors. You can see examples of both types of stencil prints in the image gallery. They are arranged in biblical chronological order; the washi prints come first, followed by momigami images

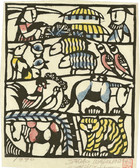

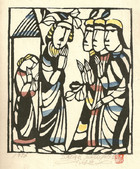

Watanabe steeped himself in the biblical texts, before beginning a new narrative print, reading them over and over to catch every symbolic nuance in the stories. Although he draws on the iconographic conventions of Western religious art, the stylized figures; multi-tiered, flat-perspective compositions; and details of dress and setting are distinctly Japanese. The menagerie in Noah's ark is drawn from the animal signs of the Asian zodiac, including the tiger, ox, horse, dog, sheep, and roosters. In The Last Supper, Jesus and the disciples sit on the floor, oriental-style, and eat sea bream fish with sushi, a menu that marks this as a festive meal.

In transposing familiar Bible stories into a foreign cultural setting, Watanabe helps us to see these events through Japanese eyes, as if for the first time, and emphasizes the universality of the Christian message. “I owe my life to Christ and the gospel,” Watanabe once explained: “My way of expressing my gratitude is to witness to my faith through the medium of biblical scenes.”

Adam & Eve

The Labor of Adam and Eve

Animal Parade into the Ark

Noah and the Ark

Abraham’s Three Guests

Jacob Wrestles the Angel

Moses in the Bulrushes

Moses Brings Water from a Rock

The Death of Moses

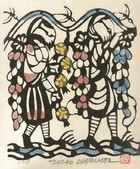

The Grapes of the Promised Land

Joshua at the Battle of Jericho

Naomi and Ruth

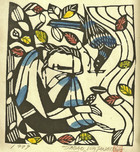

Elijah Fed By the Raven

Elijah in the Fiery Chariot

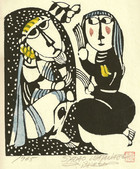

Job and His Wife

The Annunciation

The Visitation

The Nativity

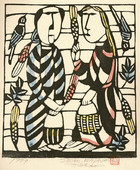

Calling the Disciples

The First Miracle at Cana

St. Peter and the Key of the Kingdom

The Woman at the Well

The Lilies of the Field

The Prodigal Son

The Good Shepherd (1975)

The Good Shepherd (1991)

The Sower & the Seed

The Poor Man Lazarus

Presentation of the Donkey

The Triumphal Entry

The Last Supper

The Last Supper (small)

Washing the Disciples’ Feet

Jeus Washes the Feet of Peter

Christ Carrying the Cross

The Crucifixion (1970)

The Crucifixion (1976)

The Myrrh-Bearers

The Resurrection

Noli me Tangere

The Road to Emmaus

Pentecost

Sharing

St. Francis Preaches to the Birds

The Women and the Quails

Madonna & Child

Nativity (1965)

The Nativity

The Three Fishermen Who Followed Jesus

Jesus Stills the Storm

Woman of Canaan

The Good Shepherd

The Good Samaritan

The Parable of the Vineyard Workers

Christ Cleansing the Temple

Handkerchief of Veronica

The Crucifixion(1991)

Jesus at Emmaus (1969)

The Risen Christ on the Mountain (1981)