Ben-Zion

(1897-1987)

The son of a third-generation cantor who sang in the largest synagogue in Galicia (now southeastern Poland), Benzion Weinman was steeped in Jewish tradition from his earliest years, destined for the rabbinate. The young Benzion had other ideas. As the story goes, he was caught making sketches in Hebrew school, and his angry father tore them to shreds. Weinman did study art briefly in Vienna but found the academic atmosphere oppressive and returned to his inherited culture of the word. When he emigrated to the U.S. in 1920, he gained recognition among Jewish immigrants in New York City as a gifted writer of poems, plays and fairy tales in Hebrew.

As the rhetoric of racial hatred against the Jews of Europe grew more virulent in the 1930s, Weinman found he could no longer write and turned to the visual arts to regain his creative voice. Shortening his name to Ben-Zion, he evolved an expressionistic style of art, grounded in the East European Jewish experience, peopled with images of the patriarchs, prophets and kings he had come to know so well from his reading of sacred texts in the yeshiva of his childhood. As the artist explained: "I know of no other book in which the apocalyptic and elementary conflicts, as well as the psychological complication of our time, come to a stronger symbolic expression than in the Bible."

For a time in the mid-1930s, Ben-Zion belonged to The Ten, a group of avant-garde artists (actually numbering nine),which included Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb. Group members worked in very different styles but were united in their opposition to the regionalist art, then, favored by public institutions like the newly opened Whitney Museum. Ben-Zion did not follow Rothko or Gottlieb into Abstract Expressionism and remained true all his career to figurative art. He claimed non-representational artists were escaping from “subject matter” to hide behind “a cloud of high sounding philosophical terms and metaphysical abracadabras.”

Ben-Zion believed works or art should never be deliberately obscure, since art-making, itself, was a mystery. He was especially drawn to “primitive and archaic” art, created from whatever materials could be found at hand without reference to theoretical rules and took pleasure in making simple sculptured forms out of iron. For him, true art and true religion worked in tandem in “confronting and recognizing the big unknown." He found the “origin symbols” of his own Jewish identity in the Hebrew Scriptures.

Ben-Zion's sacred art brings to mind the work of his celebrated contemporary, Marc Chagall, with whom he shared a common heritage as an East European Jew nurtured in a rich culture of faith that was destroyed in the Holocaust. While Chagall’s figures are aerial acrobats floating through space, Ben-Zion’s forms are firmly fixed on earth, as if sculpted out of stone--not surprising for an artist who was a lifelong collecter of rocks and pebbles. While Chagall was a colorist, Ben-Zion used a muted palette with strong black outlining, coming out of his early experiments in drawing with twigs dipped in ink.

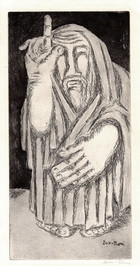

The Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection has Ben-Zion watercolors in this style on two favorite themes. One figure-study in highly-agitated black lines depicts the long-suffering Job, whose story represented for Ben-Zion the suffering and the endurance of the Jewish People. A second watercolor shows an old bearded man in a kippah skullcap, no doubt, a Torah scholar and a familiar face from the artist's childhood in the shtetls of Galicia. Ben-Zion considered the humiliation and murder of these keepers of tradition by the Nazis as the most devastating blow to East European Judaism. His features reappear in the artist's images of the biblical prophets.

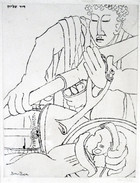

When Ben-Zion's biblical paintings were shown for the first time at the Jewish Museum in New York City in 1948, their strong graphic elements were immediately noticeable to viewers, and the artist was asked if he would consider recreating the images as prints. Ben-Zion took up the challenge and found his sacred themes only gained in emotional power, when transferred into black-and-white etchings like his often-repeated study of a pleading prophet in the image gallery. In collaboration with the New York gallery owner, Curt Valentin, Ben-Zion set to work on a quartet of portofolios on themes from the Hebrew Scriptures, each containing eighteen prints.

The Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection has a selection of etchings/aquatints from the three portfolios Ben-Zion completed in the 1950s on Biblical Themes, The Prophets, and The Books of Ruth, Job, and Song of Songs and a fourth portfolio on Judges and Kings published in 1964. Images may have become the primary means of artistic expression for Ben-Zion, but he never lost his love for language and resumed writing poems and essays until the end of his life. Each of the prints in these graphic series on biblical themes served as a visual midrash--commentary--on a specific passage from the Hebrew Scriptures, quoted in the portfolio notes.

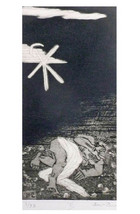

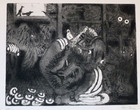

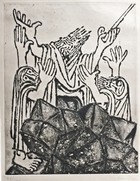

Ben-Zion's cycle of etchings are an expressionistic tour de force, using ever available artistic means to tell a story in images. His erotically-charged depictions of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and Ruth and Boaz on the threshing floor contrast both in mood and tonal values with the simply sketched figures of the Prophet and Priest from the Book of Amos and the despairing Job, whose oversized hands grasp for heaven. Ben-Zion was no fan of Modern Art, but he incorporates abstract compositional elements in his images of Lot's Wife turning to stone and Jacob wrestling with the angel to heighten the visual drama of the biblical narratives.

The print cycles appeared at a time when American Jews were coming to terms with the full magnitude of the horrors of the Holocaust in World War II, while celebrating the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. In Ben-Zion's depiction of Noah and the Ark, the release of the dove offers a glimmer of hope, drawing our eyes away from the clenched fist of a victim of the great deluge. In The Prophets portfolio, we see Ezekiel with his hands dramatically raised in the air, about to say the words, given him from God, which will restore the breath of life to the scattered skeletons in the Valley of Dry Bones.

Job

Portrait of an Old Man

The Prophet

The Prophet

Genesis 2:7 (Creation of Adam)

Genesis 3:6 (The Fall in Eden)

Genesis 4:5 (The Offering of Cain)

Genesis 7:15 (Noah & the Ark)

Genesis 8:11 (The Dove and the Olive Branch)

Genesis 19:26 (Lot’s Wife)

Genesis 32:24 (Jacob & the Angel)

Genesis 37:7 (Joseph’s Dream)

Exodus 3:2 (The Burning Bush)

Exodus 15:1 (Crossing the Red Sea)

Exodus 17:11 (Raising Moses’ Arms)

Exodus 24:12 (The Ten Commandments)

Numbers 22: 23 (Balaam’s Talking Ass)

2 Kings 2:11-13 (The Fiery Chariot)

Jonah 1:3 (The Call to Jonah)

Jonah 2:10 (Jonah Vomited Out of the Whale)

Amos 7:12-13 (Prophet & Priest)

Jeremiah 32:3 (Imprisoned Prophet)

Ezekiel 37:4-5 (Valley of Dry Bones)

Daniel 7:6 (Daniel in the Lion’s Den)

Ruth 1:16 (Naomi & Ruth)

Ruth 2:17 (Ruth Gleaning)

Ruth 3: 7-8 (Ruth & Boaz)

Job 2:8

Job 6:11

Job 9:34-35

Job 28: 12

I Samuel 17:50 (David and Goliath)

The Clash (PLate IV)

Turned Away (Plate V)