Paul Aizpiri

Like Picasso, Matisse, and Chagall, Paul Aizpiri belongs to the special category of “Mediterranean Artist,” painters whose works seem to glow with the sun of Southern Europe. Perhaps, with a mother from Italy and a father from the Spanish Basque country, the French-born Aizpiri was destined to view the world in brilliant shades of azure, carmine and gold. His busy, breathless brushwork and bright colored palette, summon up Riviera promenades, Venetian canals, motley-costumed circus performers, and bouquets of exotic blossoms, pulsing with energy and a relentless joie de vivre.

Aizpiri’s canvases are part Impressionist, part Expressionist, part Cubist, but always figurative. They are easily accessible and enormously popular. Some art critics contend they are beautiful surfaces with little depth. But there is a darker, deeper side to Aizpiri’s work, rooted in his life experience. Born in 1919, he lived through the horrors of World War II as an escaped prisoner-of-war, getting by without papers in Nazi-occupied Paris, struggling to support a wife and two children, eventually losing his wife to tuberculosis.

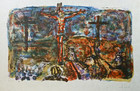

Aizpiri drew from these emotional depths in 1960 to produce a cycle of 13 lithographic illustrations for a special printing of La Passion de Nostre Seigneur, a Good Friday sermon, delivered in Latinized French in 1403 by Jehan Gerson, Chancellor of Paris University. The Head of Christ painted with gouache and watercolor on text page was one of a small number of original art pieces, included in several of the folio editions. The book is divided into two sections, each with 12 textes. Following the Holy Week narrative from the Garden of Gethsemane to the Deposition from the Cross, Aizpiri masterfully blends the medieval and the modern in a visually lacerating, hauntingly beautiful study of Christ’s Passion. A true masterpiece of contemporary sacred art.

Aizpiri created another striking image of Christ on the Cross, which came to me untitled. It seems to be an artist's proof for a lithograph he decided to abandon, showing two figures beneath a Medieval-styled Crucifix. The man on the right holds a wine goblet and is about to plunge his fork into a roasted fowl. He looks with suspicion, perhaps, guilt, toward a second figure to our left, kneeling in supplication. Could this symbolize the conflict between the desires of the flesh and the spirit in all of us? The great gulf between the rich and the poor to which Christ alluded in his parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man (Luke 16: 19-31)? Whatever the meaning, Christ’s merciful gaze is turned toward the figure in prayer.