Robert Sargent Austin

(1895-1973)

Robert Sargent Austin is one artist whose work has touched tens of millions. Austin was a consultant to the Bank of England from 1956 to 1961, and his sketch of Queen Elizabeth II was the first image of the Monarch ever to appear on a one pound note. It was a "crowning" achievement for this son of a cabinet maker from Leicester, whose drawing abilities won him a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in London in 1914.

World War I intervened, and Austin went off to France to serve as a gunner on the Western Front. Returning from the trenches, he continued his studies at the Royal College and learned print-making from Frank Short, a leading figure in the revival of etching in Britain in the 1920s. The course was set for the rest of Austin’s artistic career.

Austin’s skill as an etcher earned him a scholarship in 1922 to the British School in Rome. He stayed three years in Italy, traveling around Tuscany and Umbria, taking in local color. He also steeped himself in the works of Old Master print-makers like Albrecht Durer and Andrea Mantegna. Under their influence, he switched from etching to engraving. Once back in London, Austin joined the Royal College of Art, teaching engraving. He remained on the staff for over 30 years

In the mid-1930s, Austin converted an old Methodist Chapel in Norfolk into a studio-retreat, finding inspiration for his prints in rural life and landscapes and in private moments shared with his wife and two daughters. His work during World War II as an official War Artist left him less time for print-making. In his later years, Austin had trouble holding printing tools and turned to drawing and watercolor. He is best remembered for his elegant line-engravings.

The medium was the perfect match for the man. Austin was a artist of few (mostly frank) words and a technical perfectionist, who came to prefer the precise, clean-edged forms he could make, working directly with a burin on a metal plate to the less controlled lines of etching, which are sketched onto a waxed surface, then, deepened in an acid bath.

Austin’s prints have been criticized for their “meticulous, chilling classicism.” In reality, he is closer in style and theme to the Pre-Raphaelites, sharing their attention to detail and their desire to recreate a romanticized, pre-industrial past. One 1930s Art Historian considered Austin to be “a rebel against the precept that an artist should depict his own time.”

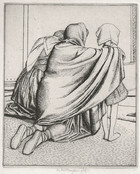

Austin was, certainly, no modernist. Religious themes weave in and out of his prints. He, frequently, portrayed figures in prayer, standing or kneeling, as in Angelus, Man with a Cross, and Women in Church (a splendid study in the flow of drapery!) The sacred often mingles with the secular in intriguing ways. Crucifixes, holy figurines and cabbage heads lie jumbled together on the ground for sale in Comare Giulia, while the heavily-burdened Wood Carriers pass a roadside shrine with the Crucified Christ, who has his own cross to bear.

Studying these prints and others like, Belfry at Palma, where the bell-ringer is fast asleep on his watch, I am tempted to read allegorical meanings into them, much as I would the works of Austin’s great mentor, Durer.