Eugene Higgins

(1874-1958)

Few American art-makers have looked at the poor, the homeless, the derelicts and discards of society with so open and compassionate an eye as Eugene Higgins. The Missouri-born painter and print-maker was the son of Irish immigrants, raised by his stone-cutter father in a St. Louis boarding house, after his mother died when he was only four. Higgins knew first hand the hardship of the socially marginalized like The Rag-Pickers in a 1908 etching or the People of the Night in an undated sepia monotype. These childhood memories defined the contours of his artistic imagination, which remained unchanged, even after Higgins gained critical recognition and commercial success in the last twenty years of his life.

Higgins is said to have painted his first picture at the age of 12, inspired by a magazine illustration of a work by 19th century French Artist Jean-Francois Millet, who was noted for his realistic studies of the rural poor. Higgins left for the homeland of his artistic idol in 1897 and studied for seven years at the famed Academie Julian and Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He became familiar with the works of the Great Masters, learned the art of etching and monotypes (a single print made off an inked surface), and returned home, largely, uninfluenced by the new art movements spreading across Europe. Higgins was already committed to expressive realism. He was one Ashcan School artist who would stay on the cinder heap all of his artistic career.

Much about Higgins’ Social Realist art suggests the country scenes of Millet and the working class portraits of another great 19th century French “Artist of the People,” Honore Daumier, but without the sentimentality of the former or the cartoonish satire of the latter. At times, his chiaroscuro studies reach the range of Rembrandt. The figures are usually huddled and earthbound, their backs bent from years of labor, as anonymous in their features as rural folk in the paintings of Peter Bruegel. Were it not for their expressive physical gestures, they could easily be mistaken for weathered shapes, emerging from the background, which, itself, becomes a bearer of emotion. One art critic in 1919 hailed Higgins’ ability to create “a despondent mountain and a grieving road.” Religious subjects fitted naturally into his artistic worldview.

Higgins is represented in the Sacred Art Pilgrim collection by 25 colored monotypes and six matching etchings on New Testament themes, commissioned in the mid-1940s for the Catholic Lending Library in Hartford, Connecticut, by Father Andrew J. Kelly, a family friend and astute collector of contemporary American art. Higgins did not follow traditional cycles of sacred imagery in creating his Life of Christ, omitting key events like the Baptism of Jesus and the Transfiguration. He accents, instead, the poverty of the Holy Family, the rural, working class origins of Christ’s followers, and Jesus’ message of hope to the despised and downtrodden.

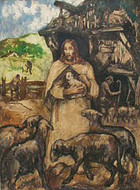

For me, the defining image of the series is The Poor Have the Gospel Preached to Them, where Christ enters the humble home of modern peasants, much in the style of popular 19th century prints by German Artist Fritz von Uhde. Mary and Joseph in There Was No Room at the Inn look like neighbors Higgins might have seen evicted from their rooms in the St. Louis slums of his childhood, while Jesus the Good Shepherd in For These Sheep I Lay Down My Life could be a farm hand in Lyme, Connecticut, where the Higgins family spent their summers. Higgins gives deeper, richer meaning to Christ’s words about himself in Matthew 8:20 (KJV): “The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests; but the Son of Man hath not where to lay his head.”

The Rag Pickers

People of the Night

There Was No Room for Them in the Inn

And This Was the Manner of Christ’s Birth

Wondering Over All That Was Said of Him

Andrew Brought His Brother Simon Peter to Jesus

Simon, Andrew, James, and His Brother John

The Poor Have the Gospel Preached to Them

No Man Laid Hands on Him

They Waited at Early Morning to Hear Him

For These Sheep I Lay Down My Life

There Came a Certain Widow

Veronica Daughter of Jerusalem

Obedient Even to the Death of the Cross

Then Peter Remembered the Words of Jesus

Take With Thee the Child and His Mother

I Must Go Up to Jerusalem

Stabat Mater Dolorosa