Jaroslav Vodrazka

(1894-1984)

Czech Artist Jaroslav Vodrazka belongs to a special generation of East European intellectuals who lived through one of the most turbulent times in modern history. Born under Austro-Hungarian rule, they welcomed the break-up of the Empire in World War I and a brief time of national freedom and cultural renewal in the interwar period, only to endure Nazi Occupation in World War II, then, Soviet domination in the post-war years, enforced in Hungary and Czechoslovakia with armed interventions. A blessed few lived to see the collapse of the Soviet Bloc. Vodrazka was not one of them. He died five years before the Velvet Revolution of 1989 swept the Communists out of power in his homeland.

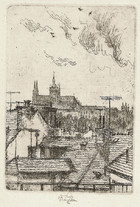

Artists of this marked generation, like Vodrazka, became “internal émigrés” who paid lip service to alien political systems, as far as their consciences would allow. They experienced real life with family, friends and artistic colleagues in cramped apartments, overflowing with books, musical recordings, and art objects, which offered them windows into the closed outside world. Vodrazka had just such a place of refuge on the West Bank of the Vltava River in Prague with a view of the spires of St. Vitus Cathedral, a scene he frequently depicted in his etchings. The art teacher, painter, print-maker, and illustrator lived there from 1939 with his wife, Ella, a writer-poet who collaborated with him on children’s book projects. Their son, Jaroslav, became a noted classical organist and professor of music.

The son of a miller who married a baker’s daughter and set up a bakery in Prague, Vodrazka showed artistic talent at an early age, drawing on sidewalks and the margins of newspapers. He attended a school for the applied arts, where he mastered print-making, and was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army in World War I, capturing life on the Alpine front in Italy and in military hospitals in sketches and watercolors. With the post-war creation of a Czechoslovak state, Vodrazka was appointed as art teacher to a school in Bohemia, then, sent in 1923 to Svaty Martin in Slovakia, where he played a key role over the next 16 years in developing book design and typography in the Slovak language, suppressed during the period of Hungarian rule .

When a Fascist regime in Slovakia purged ethnic Czechs from state jobs on the eve of World War II, Vodrazka returned with his family to Prague in the Nazi-run Protectorate. With the world changing all around him, he settled into a life of teaching, book illustration, and print-making, experimenting in the post war years with a variety of graphic techniques. Vodrazka occasionally made large scale sketches for the decoration of public buildings, especially churches, but his real passion was for intimate, small-format prints and ex-libris book plates, commissioned by collectors who wanted special subjects, symbols, and scenes incorporated into these miniature graphics.

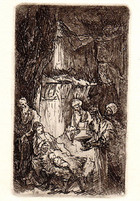

Religious themes were important to Vodrazka. A biography of the artist, written in the Communist era, offers the telling detail that he kept his own painting of St. Vaclav, the Czech national patron, better known in the West as Good King Wenceslas, in his inner sanctum library, along with a folk art carving of the Resurrection and a collection of prints by great masters of sacred art like Martin Schongauer, Albrecht Durer, and Rembrandt. His archives include sketches of ecclesiastical decorations for a chapel in St. Vitus Cathedral, never realized, and studies for stained glass windows for the Neo-Gothic Church of St. Ludmila in Prague and sanctuaries in Pilsen and the Banska Bystrica region.

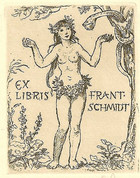

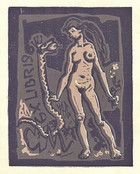

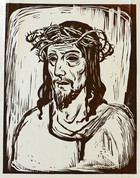

The small prints and ex-libris by Vodrazka in the gallery depict everything from St. Vaclav, St. Martin, and The Madonna Painter (perhaps, St. Luke) to the Temptation of Eve, the Passion of Christ, and the Parable of the Prodigal Son. A chapel crowns a hill in a woodcut of a Bohemian landscape. Two important strands of Vodrazka's work come together in an etching of Don Quixote keeping vigil at the Cross. The Dreamer of Impossible Dreams was a favorite subject of this Czech Printmaker who hoped for a brighter future for his homeland that he would not live to see.

If I were to pick one image, typifying Vodrazka’s aesthetic-moral vision, it would be the small-format etching of a dying saint, pierced with arrows and hanging from a tree, combining motifs of the Crucifixion and the slaying of St. Sebastian. Examining this little piece, titled The Martyr, with a magnifying glass, I noticed one telling detail that had escaped my notice. Attached to the tree trunk is a slip of paper with the numerals: 21. VIII.1968. It is the date of the Moscow-led Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, which brought the Prague Spring and any hopes of creating “socialism with a human face" to an end. In this poignant little print, Vodrazka symbolizes the martyrdom of his homeland.

View of St. Vitus Cathedral

Temptation of Eve I

The Temptation of Eve II

Tobias and the Angel

The Nativity

The Flight into Egypt

Christ Carries the Cross

Head of Christ

The Man of Sorrows

The Man of Sorrows

The Resurrection

The Prodigal Son

The Good Samaritan

St. Vaclav

St. Martin Divides His Cloak

The Madonna Painter

Chapel on a Hill

Don Quixote at the Cross