Dora Maar

(1907-1997)

Mention the name, Dora Maar, in art circles and you will hear cash registers ring. The Cubist-deformed features of this onetime mistress and muse of Megastar Pablo Picasso appear in two of the most expensive paintings ever sold at auction. Femme assise dans un jardin, showing Maar seated in a garden, fetched $49.6 million in bidding in 1999. Picasso’s portrait of Maar and a black cat, Dora Maar au chat, brought in an even more impressive $95.2 million in 2006.

As the model for Picasso’s Weeping Woman pictures, Maar has entered art history (and legend) not only as the artist's icon of Suffering Spain under Fascism but as the classic embodiment of the spurned mistress, driven to hysterical tears and madness by her unfaithful (art-genius) lover. It may come as a surprise to hear Maar deserves recognition as a gifted maker of contemporary sacred art.

Born in Paris to a Croatian father and French mother, Henriette Theodora Markovitch emigrated with her parents, at age 3, to Buenos Aires, Argentina, where her father found work as an architect. She returned to France 16 years later to study painting and photography and got herself a fancy new name: Dora Maar.

With her exotic looks, extravagant hats, and brightly-painted finger nails, Maar became a fixture in French Surrealist art circles of the 1930s. A friend of Photographers Man Ray and Brassai, she became famous in her own right for her avant-garde photo-montages and pictures in dramatic perspective, as skilled in fashion photography as she was in shooting street life among the urban poor.

Picasso was first drawn to Maar in 1936, when he saw her at a Paris café table, flicking a knife blade between the fingers of her gloved hand. With her passionate temperament, keen intelligence, leftist-political views, and fluency in Spanish, the photographer-painter was a perfect match for the Master of Modern Art. She was soon drawn into a complicated menage a quatre with Picasso’s wife, Russian Ballet Dancer Olga Khokhlova, and his mistress of the moment, Marie-Therese Walter.

Maar’s tempestuous liaison with Picasso would last almost ten years, corresponding to his most productive period of art-making. She assisted Picasso in creating Guernica, considered by many to be the greatest masterpiece of 20th century art, and left behind an invaluable photo chronicle of the artist at work on the painting.

When Picasso met Francoise Gilot in 1943, Maar got pushed off her pedestal. As Picasso told Gilot, there were two kinds of women, “goddesses and doormats,” and Maar was soon relegated to the second category. When the break between Maar and Picasso became final three years later, she suffered a nervous breakdown.

Maar remained obsessed with Picasso until the end of her life, closely monitoring the value of his works on the art market, cherishing every scrap of paper he had ever given her. But she was able to pull her life together with help from a new “Lover.“ Maar found religious faith and became a devout Roman Catholic. As Maar put it: “After Picasso, God.”

As Maar grew older, she became increasingly reclusive, commuting by taxi between her Paris apartment on the Rue de Savoie, where she had moved in 1937 to be close to Picasso’s studio, and a ramshackle house the artist had given her in a village in Vaucluse in Southeastern France. Maar made art all during her affair with the Modernist painter, but her works from the latter part of her life, when she lived in almost monastic seclusion, are less influenced by Picasso, often giving expression to her faith in an intimate, minimalist, mystical style.

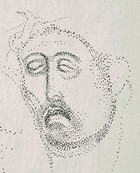

There are five ink sketches from this period in the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection, all images of Christ. Head of Christ I is a traditional pen and ink sketch with two Cubist-styled figures at the lower right. Maar turned to felt tip pens to create more delicate, pointillist images like Head of Christ III and Man of Sorrows, where the thorn-crowned head of Christ emerges from swirls of tiny dots. In Christ Crucified & Notre Dame, the speckled forms are so faintly drawn, they seem like shimmering mirages.

The woman who made voyeuristic fashion photos and became, herself, an object to be gaped at by millions in paintings on gallery walls and in photo reproductions took a different view of what it meant to see and be seen in her years without Picasso. She recorded her feelings in a poignant prayer in poetry, as spare and austere as the life style she chose for herself:

I am blind

and made from a bit of earth

But your gaze never leaves me

And your angel keeps me

Biographical material from Dora Maar: With and Without Picasso by Mary Ann Caws (Thames & Hudson, Ltd., London: 2000)