Helen Siegl

(1924-2009)

Austrian-born Printmaker Helen Siegl spent most of her life in the U.S., but her aesthetic creed was forged by her experiences in her home city of Vienna during the traumatic years of Nazi Annexation, World War II, and the post-war Soviet occupation. Many European artists of her generation came through this fiery furnace embittered and alienated by the death, destruction, and degradation they had witnessed. A devout Roman Catholic, Siegl was able to transcend the horrors of the past in works of art, informed by faith and compassion, celebrating the mysteries of belief, the joys of community, and the wonders of God’s good creation, rendered in the tiniest details of dandelion fluff and peacock plume.

Siegl studied architecture and design at the Academy (now University) of the Applied Arts in Vienna, the alma mater of Gustav Klimt and Oskar Kokoshka, but her passion for graphic art grew out of hours spent at the city’s Albertina, which houses one of the world’s greatest print collections. Siegl expressed her faith through art early in her career in illustrations for a children’s magazine, founded by Benedictine Monk David Steindl-Rast. For a time, she even considered becoming a cloistered nun at the Nonnberg Abbey, made famous by the musical film, The Sound of Music. Like Maria von Trapp, Helen chose the secular path, emigrating to Canada, where she married Theodore Siegl in 1952.

When Theodore was appointed conservator of paintings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the couple settled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Helen raised eight children, but still found time to pursue printmaking, digging grooved images onto wood panels, linoleum, and even plaster blocks, a technique she developed in the war years, when wood was scarce. She won recognition for her illustrations of everything from Aesop’s Fables and Mother Goose to Turkish and Nigerian folktales. The Sacred Art Pilgrim library has two books with Siegl illustrations: Adam and Eve by Gwendolyn Reed and A Felicity of Carols, a selection of Christmas songs with wood engravings.

In later years, the artist felt the call of the contemplative life, again. A widow with grown children, she moved to a chalet in upstate New York to be close to the Mount Saviour Monastery, a religious community of the Benedictine rule, where the family had gone on retreats since the 1950s. Her old friend and fellow Austrian émigré, Brother David Steindl-Rast was a senior member there. As long as her health allowed, Siegl made the one mile trek to the monastery each day through pastures and woods for morning Mass and evening Vespers, using the hours in between to work on prints in the signature style she had adopted early in her career, recalling both folk art prints and German Expressionist graphics.

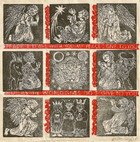

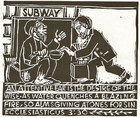

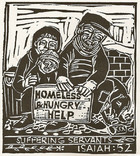

Siegl lamented the fact that celebrated contemporary artists no longer felt a responsibility to the greater community. She considered art-making to be a form of Christian service and made her prints available for reproduction in church publications in special volumes like Clip Art of the Old Testament and Clip-Art: Block Prints for Sundays, Cycles, A-B-C, both in the Sacred Art Pilgrim library. The artist’s passionate concern for social justice, shaped by her experiences in war-torn Europe, comes through clearly in her illustrations for Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) 3:30, Isaiah 52, and Isaiah 58:7, taken from the Old Testament clip art series.

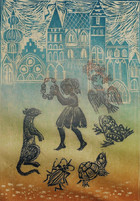

For Siegl, art and religion shared a common quest for “mystic experience.” She believed the artist had a prophetic mission to “wake people out of numbness” and present life as a “new creation.” Her art-making revels in the complexities of nature but points to the New Heaven and Earth to come. In prints like Rejoice & Be Glad and Mystic Dance, the boundaries between the physical world and the life of the spirit dissolve, and we catch a glimpse of the Peaceable Kingdom, where children form a ring with tortoise, toad and beetle and defy gravity in a line dance reaching toward the sun.

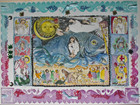

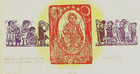

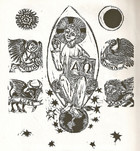

Siegl’s favorite themes come together in The Icon, a hand-painted lithograph, unusual in her body of work. Christ, portrayed as Jonah in the belly of the whale, is the central motif of the piece, while St. George and St. Nicholas keep watch from the frame with cherubs and angels. The procession of humans and animals on dry land, below the swirling waves, recalls both the story of the Exodus and Noah’s Ark. In the upper tier, the angel with trumpet and the disembodied hand, offering the sun, moon, stars, and planets, hint at the Creation of the World and its apocalyptic end. Theology combines with whimsy in a playful print, decorated with ribbons and cut-out stars.

The Icon

The Apple

After the Fall

"There Was No Room in the Inn"

Christmas Story

Peace I Leave with You

Breaking of the Bread

Thou Shalt See the Son of Man Coming on a Cloud

Rejoice & Be Glad

Mystic Dance

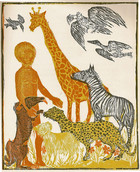

Adam Names the Animals

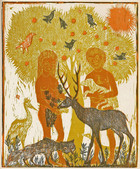

Adam & Eve in the Garden of Eden

Eating the Forbidden Fruit

Expulsion from the Garden of Eden

The First Nowell

While Shepherds Watched

What Child is This?

We Three Kings of Orient Are

Genesis 7

Job 2:13

Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) 3:30

Isaiah 52

Isaiah 58:7

Christmas

Easter

Alpha & Omega