Jose Ignacio Fletes Cruz

Nicaraguan Painter Jose Ignacio Fletes Cruz is a Primitivista artist, whose naif style of image-making is associated with a utopian Christian community, founded in the mid 1960s by Roman Catholic Poet-Priest Ernesto Cardenal in the remote Solentiname island chain at the southern end of Lake Nicaragua. A disciple of Trappist Monk Thomas Merton, the Nicaraguan cleric was an ardent proponent of Liberation Theology and believed the church should actively support the poor in their struggle for social and economic justice. Soon after Cardenal arrived on the main island of Mancarron, the parish church became a center where the fishermen and farmers of the archipelago could learn about art, poetry, and radical Christianity, and the Solentiname community was born.

Cardenal noticed the islanders were skilled in decorating gourds, and invited Nicaraguan Figurative Painter Roger Perez de la Rocha to come to the community in 1968 to give art lessons. Many of the locals knew so little about art-making, they thought, at first, the metal tubes of oil paint were colored tooth paste, but they took up painting on canvas with enthusiasm. Soon whole families were creating landscapes, typical scenes from village life, and stories from the Bible in the naif folk art style, which has come to be known as Nicaraguan Primitivism. Fletes Cruz was an outsider who came to islands to take part in the unique social experiment. Born in Managua, he had taken art courses in Leon and shared the community’s Christian ideals and egalitarian politics.

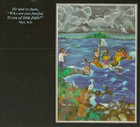

In place of the traditional homily at Sunday Mass, Cardenal encouraged members of the Solentiname community to express their own views about the Gospel readings. The discussions were later taped and transcribed to become The Gospel in Solentiname, first published in four volumes in 1975. An excerpted edition with illustrations by local Primitivista artists, appeared in 1984, titled, The Gospel in Art by the Peasants of Solentiname. A painting by Fletes Cruz accompanies the community commentaries on the Gospel narrative of Christ stilling the storm in Mark 4: 35-41 and Matthew 8: 23-27, a story close to the heart of the island's fisher folk and the subject of several Fletes Cruz canvases, including one in the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection.

The community’s involvement in the Sandinista National Liberation Front’s war against Dictator Anastasio Somoza ultimately led to its destruction in October 1977. After Solentiname activists took part in a raid against a National Guard barracks on the mainland, the Somoza militia retaliated by burning the island settlement to the ground and killing unarmed peasants. Cardenal, Fletes Cruz, and other survivors fled to Costa Rica. When the Sandinistas came to power in 1979, Cardenal became Minister of Culture in the new revolutionary government and set about rebuilding the Solentiname community. Fletes Cruz returned to Leon, became an art teacher, and joined a group of Primitivista painters in the city’s Sutiava barrio.

Much of the art coming from the Solentiname islands these days has a picture postcard prettiness about it, but Fletes Cruz has remained true to the original ideals of the community. As artist-in-residence at Gettysburg Lutheran Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania in 2004, he created a mural over nine days with help from students and faculty on the theme, “I Want Peace for My People,” depicting Christ in a t-shirt and blue jeans, preaching to a crowd gathered in a stylized Nicaraguan landscape. Fletes Cruz created a second communal mural on the Sermon on the Mount in 2007 for the library at Lancaster Theological Seminary, also in Pennsylvania, welcoming would-be painters from the surrounding community to take part.

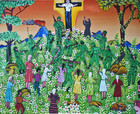

The canvas paintings by Fletes Cruz in the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection present familiar stories from the Bible in lush, tropical settings, typical of the Solentiname islands, and recall moments in the life and history of the community. In Birth of the Messiah, visitors in modern dress bring gifts to the Holy Family, who have sheltered in a grass-roofed hut, while angelic heralds float above a range of volcanic peaks. Fletes Cruz’s depiction of Jesus Christ Crucified (The Christ of the Poor) brings to mind the 1977 attack on the community by the Somoza National Guard, who appear beneath the Cross, wearing U.S. military-issue camouflage outfits.

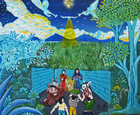

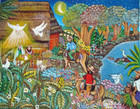

Utopian themes appear throughout his work. In The Second Chance, the ark in which God spared Noah, his family, and a remnant of creation from the divine punishment of the Great Flood now functions as a vibrant meeting place for a diverse but welcoming community of men and women, the old and the young, folks in modern dress and biblical garb. This present world order has passed away in New Heaven and New Earth, as peasants joyously welcome the Kingdom of God on earth. Fletes Cruz describes his art as “a visual representation of the revolution of Christ, of what Christ is doing within us.”

Cover of The Gospel in Art by The Peasants of Solentiname

Jesus Stills the Storm

The Second Chance: the Ark of Noah

David Kills Goliath

The Good News

Birth of the Messiah (2011)

The Visit of the Three Kings

Jesus Stills the Storm (2011)

The Holy Supper

Jesus Christ Crucified (The Christ of the Poor)