The Master of the Stalag VI D Stations

Nothing can be said with any certainty about the artist who created the Stations of the Cross drawings in this image gallery, but their place of origin is infamous. On seven of the half-folded or cut manila paper sheets in the loosely bound series you will find the red ink oval stamp mark, GEPRUFT 37 STALAG VI D, confirming the pages were inspected by Censor 37 at Nazi Concentration Camp VI D in Dortmund, Germany. A few barely legible words in French scribbled on two of the drawings suggest the artist was probably a French or Belgian soldier, one among 70,000 prisoners of war--10,000 at any given time--who passed through or were interned in Stalag VI D from 1939 to 1945.

Today, only a rough stone memorial marks the location of Stalag VI D, which was destroyed in Allied bombing raids in the last months of World War II. It was first housed in the Westfalenhalle, an exhibition pavilion considered at one time to be the largest in Europe, hosting trade fairs, congresses, and cycling events. When no more multi-tiered bunk beds could be squeezed into the huge, oval-shaped building, the inmates were moved outdoors into wooden barracks built on the grounds of the surrounding recreation park. Stalag VI D was a key registration center for forced-labor, prisoner-of-war work details, sent out to the steel mills and factories of Germany’s heavily industrialized Ruhr region.

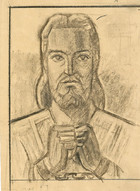

The artist who created this beautiful cycle of conte crayon drawings was a skilled draughtsman, whose geometrically-stylized forms and sinuous outlines show the influence of Art Deco design. His vignettes along the Way of Sorrow are intimate close-ups, dwelling on faces, eyes, hands, and in one case, nail-pierced feet. The series begins with the Station I image of a haunting Christ in full frontal view, displaying his chained hands, and ends with the Station XIV image of a dead Christ in sharp profile, his body laid out like a corpse on a morgue slab. There are finished drawings for all the Stations, except for a rough sketch of Station VI, where the veil Veronica offers to Christ is barely visible.

It is impossible to imagine how anyone who spent as many as 16 hours a day in front of a steel plant blast furnace could have returned, starved and exhausted, to lice-infested barracks and found the will to create sacred imagery of such calm, contemplative beauty. Art can be valued in many ways, but these sketches are especially precious as visual documents to enduring faith in the most horrible of circumstances. Following the common practice of identifying unknown artists by a particular work and its location, I have dubbed the anonymous maker of these poignant images of the Passion of Christ as the Master of the Stalag VI D Stations.