Ave Maria

The image of mother and child is deeply embedded in the collective memory of humanity, summoning up feelings of security and belonging in every culture. Christian doctrine gives this universal symbol multi-layered, paradoxical meanings. The mother depicted is a virgin, who will conceive when “the Holy Ghost shall come upon thee and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee. (Luke 1:35, KJV)" The helpless baby she holds is predestined to sacrifice his life as “the Lamb of God which taketh away the sin of the world. (John 1:29, KJV)”

There is nothing sentimental, then, in images of the Madonna. Traditional Byzantine images of Christ's birth (on which The Nativity is based) often show Mary giving birth to Jesus in a cave, resembling a tomb. When Mary and Joseph present the Baby Jesus in the Temple, the Prophet Simeon warns the new mother about her son's fate, telling her "a sword shall pierce through thy own soul, also. (Luke 2:35 (KJV)" The mother cradling the young child in her arms is echoed in lamentation scenes, called Pieta, where the Virgin Mary tenderly embraces her son, this time, after his lifeless body has been taken down from the cross.

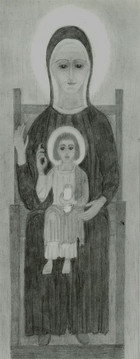

The artists of the Renaissance are unsurpassed in their rendering of the radiant but subtle flesh tones of young motherhood. But as sacred art, such naturalism becomes distracting for me. Viewing a Virgin Mary by Raphael, I can’t help wondering if she was modeled on the local fruit seller’s daughter or his latest mistress. The stylized abstraction of Byzantine icons seemed cleaner, clearer to my pilgrim eye, when I first began to explore this theme in my art.

I learned there are four basic ways of showing the Madonna in iconography— the Virgin of the Sign (with the Christ child contained in Mary's circular womb), the Virgin Who Shows the Way (with Mary's hand pointing toward her son who holds the scroll of his divine authority), the Virgin of Tenderness (with mother and son touching cheeks in a warm embrace), and the Virgin Enthroned. Even given these strict parameters, iconographers were still able to come up with over 200 different variations!.

Our Lady of Vladimir, a Byzantine icon brought to Russia in the 12th century, is the perfect embodiment for me of the Virgin of Tenderness style and the inspiration for one study here, Our Lady of Tenderness. Looking at this image of maternal love, you can easily understand why the Madonna and child became the favorite religious theme of medieval Europe, infusing a faith dominated by patriarchal imagery of kingship, hierarchy, and power with the feminine virtues of charity and compassion.

I tried to suggest something of the universality of imagery of the Virgin in my rendering of the Pieta. I wanted Mary's features to seem carved in stone, an immutable surface for superimposing the face of thousands of mothers hugging lost children, the victims of war, famine, natural disaster, sectarian violence or a random bullet.