Christe Eleison

“The Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us.” There is, probably, no more revolutionary credo in religious art than this passage from the prologue to The Gospel of John. While other monotheistic faiths banned images of living things as a form of idolatry, these words became a proof text during theological controversies in the early Christian church over the making of icons (sacred images), championing the right of artists to depict Jesus Christ in portraits. After all, didn’t the very Creator of the Universe come into the world as a “divine icon” in the person of Jesus, a man with a face and nose and eyes and ears, whom we could have seen for ourselves, had we lived in 1st century Palestine?

The key question, challenging sacred artists ever since, is just how to portray Christ. The Gospel narratives provide no physical description. Early representations of Jesus the Good Shepherd in the Roman catacombs and the 5th century mosaics of Ravenna show a beardless, young man. The Latin West tells of a portrait left on a veil, which a woman named Veronica (“true icon”) had used to wipe the face of the fallen Christ on his way to Calvary. The Eastern Orthodox revere an image “made without hands,” which Jesus is said to have imprinted on the linen cloth he sent to heal the ailing King of Edessa. My own childhood impressions of Jesus were formed by Warner Sallman’s 1940 Head of Christ, a favorite among conservative American Protestants, depicting a kindly, Nordic featured man, who looks like he’s never been near a carpenter shop.

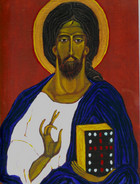

Two images of Christ have had special meaning for me in my artistic journey. The first is the 6th-7th century Christ Pantocrator (Lord of the Universe), one of the earliest surviving panel paintings of Jesus, which I was fortunate enough to see on a pilgrimage to St. Catherine's Monastery at Mount Sinai. When you examine the face of the bearded young man, masterfully rendered in the style of a Greco-Roman funeral portrait, it seems to divide into two, the right side, depicting the stern Christ of judgment; the left, the serene Christ of blessing.

The second image is the 14th century Russian icon of Christ the Savior, which Andrei Rublev made for an icon screen in Zvenigorod, (rescued from a barn where it had been abandoned as scrap wood during the mass destruction of churches that followed the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution!) The face of Christ miraculously preserved on this badly damaged panel is both mysterious and majestic, calm and compassionate, in ways seldom seen in Orthodox iconography. It is a favorite destination, when I visit the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. Two images in this gallery, Christ the Savior I and Christ the Savior II are loving derivations of the Rublev icon.

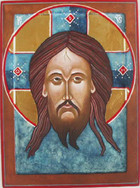

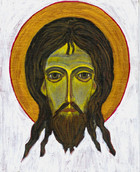

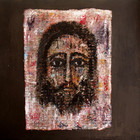

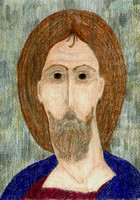

True icons, by the way, are written, not painted. I have only made one icon, so far, in the time-honored tradition of egg tempera paint on gesso-treated wood panel, a copy of the Eastern Orthodox Made Without Hands prototype. There is an acrylic study on the same theme in this gallery, (something my icon instructor would call "invented art"!), as well, a painting of Veronica's Veil. The Good Shepherd presents a rough-hewn, earthy Christ with nail-pierced hands--in marked contrast to the gentle Jesus, meek and mild, who appears in traditional renderings of this image--a shepherd who would really lay down his life for his sheep!