Divine Geometry

The square and circle are the building blocks of artistic composition. They are also powerful symbols. The square represents what is finite and bounded. The circle, the infinite and boundless. This duality of form and meaning made the square and circle the perfect starting point, when I started to experiment with abstract sacred art, inspired by the ultra-geometric forms of Le Corbusier's Notre-Dame-du-Haut chapel in Ronchamps, France.

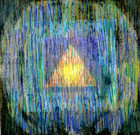

In the simplest variation, the bright-colored circles of my Resurrection series contrast with the black-tinged squares of the Dark Night of the Soul panels. In Gethsemane the Divine geometry becomes more complex. I boxed the central bright circle, enclosing a red and blue rectangle (traditional iconographic coloring for the humanity and divinity of Christ) within a series of rough edged squares of conflicting tonal values to evoke Christ's spiritual struggle, as he awaits arrest in the garden. And the Darkness Comprehended It Not (from the prologue of The Gospel of John) introduces a shimmering triangle—and all its associations with The Trinity—into a composition of intersecting squares and circles.

Resurrection After Grunewald takes a different approach. A recognized icon of Christian art, the magnificent Resurrection panel from the Isenheim Altar by 15th-16th century German master, Matthias Grunewald, is broken down, here, into its most basic geometric shapes. The flaming yellow circle and the triangle in glowing red are what the eyes first perceive in the painting, before we assign meaning to these forms and recognize the figure of Christ rising from the grave.