New Mexican Saint-Makers

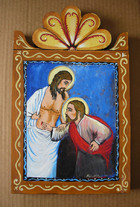

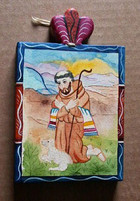

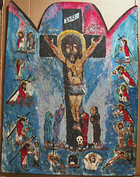

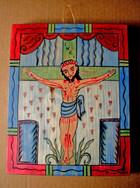

One destination that should be on the itinerary of every serious Sacred Art Pilgrim is New Mexico, the home of a thriving religious folk art tradition, dating back to the arrival of the first Roman Catholic missionaries from Spain over four centuries ago. If we can speak of a distinctly American school of icon-making, then, it would, certainly, be found, here, among the painters of holy images in the American Southwest.

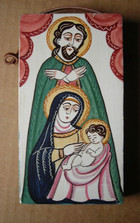

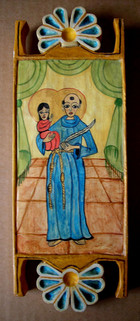

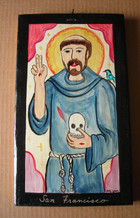

New Mexico was one of the out-lying territories of the New World, so, images of Christ, the Virgin Mary and the saints (called santos), became vital visual aids in helping Spanish settlers and Native American converts keep their faith in the long intervals between visits by itinerant priests. With holy artifacts from Spain and Mexico always in short supply, local artisans, who came to be known as santeros (saint-makers), developed an indigenous school of retablo panel painting not unlike the iconographic tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church both in its mode of preparation and importance to the devotional life of the faithful.

The coming of the railroads in the 19th century brought New Mexicans mass-produced plaster saints and holy postcards in plenty, and the art of the santeros went into decline. It was successfully revived by enthusiasts from the Spanish Colonial Arts Society, founded in 1925. The organization sponsors the Spanish Colonial Market in Santa Fe every summer and winter, offering santeros a chance to display their works in juried competition.

Folk art collectors eagerly await the opening of the Market to pick up the latest pieces by modern santeros, many of whom, like Marie Romero Cash, are second and third generation saint-makers. The Gonzales family of Albuquerque is another example of a New Mexican artisan “dynasty.” Father Roberto paints santos, sons Robert, Jonathan and Desmond produce Spanish Colonial-style furniture, and grand daughter Adriana was one of the youngest participants in the Spanish Market.

According to standards set by the Spanish Colonial Arts Society, a traditional santos painting should be made on hand-carved panels of wood, primed with homemade gesso, using natural water-based pigments, and pinon pine sap varnish, though many contemporary santeros have succumbed to the temptation of acrylics.

There are no strict canons on themes or painting styles, but modern artists tend to draw inspiration from the works of old santero masters. Panels come in a variety of forms, sometimes with carved edges like bas-relief or with intricately hammered metal frames. Usually, they are hung from a simple leather strap.

Despite growing commercialization of the craft, many santeros still work in a deeply-rooted faith tradition, talking of the inspiration they receive directly from their favorite saints. Lydia Garcia even sends a blessing to those who buy her panels with personal prayers written on the back. In our cynical, secular age, that, in itself, is a miracle.

James Cordova

Ruben Gallegos

Frank Garcia

Frank Garcia

Lydia Garcia

Lydia Garcia

Lydia Garcia

Lydia Garcia

Roberto Gonzales

Genevieve Leitner

Angelica Lopez

Jose Lucero

Tim Lucero

Mary Jo Madrid

Mary Jo Madrid

Jerry Montoya

Carlos A. Rael

Catherine Robles-Shaw

Ellen Santistevan

Ellen Santistevan

Ellen Santistevan

Marie Sena

Vincente Telles

Gabriel Vigil