Russian Lacquer Art

Resplendent with images of snow maidens, frog princesses, troikas and firebirds, Russian lacquer boxes would seem to have no connection to the world of sacred art. But these highly valued folk art pieces owe their very existence to artisans of the Russian Orthodox Church. Snuffboxes and other painted lacquer objects were made in the village of Fedoskino, near Moscow, from the end of the 18th century onwards, but the Russian lacquer box, as we know it today, is a product of the Communist era.

After the anti-religious campaign that followed the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 left hundreds of icon-writers in the Russian heartland without work, the new regime organized them into cooperatives to paint lacquer boxes. Holy images were taboo, but the atheistic authorities could not keep religion completely out of the picture. Paint a Russian landscape and onion-shaped domes and church bell towers were bound to appear somewhere! And so they did, in hundreds of artistic variations on boxes of all shapes and sizes.

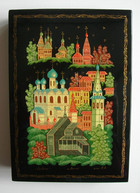

Russian lacquer boxes come from four main locations: Fedoskino, the original lacquer-working center, and Palekh, Kholui, and Mstera, villages in the Golden Ring of historic cities, north of Moscow, once famed for their iconographers. Like oriental lacquer ware, Russian boxes are made by pressing multiple strips of cardboard around a mold. The box form is, then, boiled in linseed oil and baked in an oven. The finished material, which has the consistency of wood, is treated with primer, and painted with as many as thirty coats of lacquer, black on the outside, and cinnabar red on the inside.

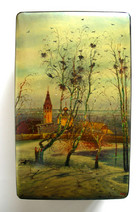

The miniature images take shape in multi-colored layers, painted one over the other in ever increasing detail, similar in technique to iconography. Each layer of imagery is covered with a clear coat of lacquer, before the next one is added. Several more layers of clear lacquer seal in the picture, before the box goes back to the oven for a final baking. (See the Village Panorama box from Kholui decorated on both lid and sides). While Fedoskino box makers paint in oil, artisans in the three other villages still favor egg tempera, the traditional medium of icon-writing.

Fedoskino boxes have the look of miniature oil paintings and are often reproductions of works of 19th century Russian Realist art. (There is a fine Fedoskino box in my collection, depicting Alexey Savrasov’s much-loved late winter landscape, The Rooks Have Returned.) Kholui lacquer ware is easy to recognize by its bold, bright imagery, painted in flattened perspective with the black background left visible. Mstera lacquer pieces have softer colors in pastel tones, covering over the black background. Almost all of the lacquer boxes shown in this gallery come from Kholui village and date from the end of the Soviet period in the 1980s, when I worked as a journalist in Moscow and collected boxes with scenes of sacred architecture.

The architectural riches on view range from wooden chapels of the Russian North to churches on the Moscow River embankment. In an era when many sacred spaces had been vandalized or converted into warehouses, garages, and even prisons, lacquer boxes depicted a Russia of faith, where Orthodox shrines were viewed as the crowning glories of the landscape. With the return of religious freedom to Russia, all has come full circle and contemporary box makers are taking up iconographic themes.

The revival of sacred art-making anywhere in the world these days is a cause for celebration, especially in the former Communist bloc, so, I was delighted to discover the work of Alexander Gaun, a painter from Mstera, who was born in a village of the Golden Ring region and learned his trade during the Soviet era at the Mstera Art Institute and Technical School. Gaun specializes in biblical subjects, depicting scenes from Genesis straight on through to Revelations. Working with a palette in which earth tones predominate, Gaun follows the iconographic tradition of merging separate events together in a single “eternal” space.

Gaun's rendering of the Nativity, taken from the second chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, shows the Wise Men from the East conferring with King Herod, bringing gifts to the Christ Child, and returning home by another way, while the Slaughter of the Innocents unfolds in the center of the panel. In Golgotha, we follow Christ from the betrayal scene in the Garden to the trial before Pilate (glimpsed, washing his hands), along the Way of the Cross to his Crucifixion. In The Prodigal Son, based on Jesus's famous parable in Luke 15:11-32, the story begins and and ends at the central doorway, following a circuitous, clockwise path around the panel. The Tower of Babel takes us from the planning and construction of humanity’s first skyscraper to it’s leveling by angels.

The growing market for religious objects in Post-Communist Russia has motivated lacquer artists to move beyond traditional box-making to create stylish pieces like the Vladimir Mother of God Triptych in the collection from Mstera Folk Artist “Yu. Maleev.” It is made with folding panels in the portable format of once ubiquitous travel icons. Resembling the Royal Gates of an Eastern Orthodox iconostasis in miniature, two lacquer doors painted with images of the Archangels Michael and Gabriel open to reveal a luminous iconic variation of the Vladimir Mother of God, one of Russia’s most revered icons. The hinged side panels on the left and right depict the Apostle Peter, the founder of the Church, and John the Baptist, always shown with the Virgin Mary standing beside Christ in Deisis (Prayer) icons. Heaven and earth in little space!

Village Panorama

Village Panorama (Suzdal)

Village Panorama (Palekh)

Village Panorama (Uglich)

Village Panorama (Plyos)

Village Panorama (Kholui)

Plyos Village

Pokrovsky Monastery

The Russian North

Moscow River Embankment

Kholui Village

Kholui Village

Suzdal Village

The Rooks Have Returned

Kholui Village

Kideksha Village

Wooden Churches of Suzdal

In the Hills

Suzdal Village

Danilo Village

The Kremlin in Rostov

The Tower of Babel

Nativity

The Prodigal Son

Golgotha

The Vladimir Mother of God Triptych (closed)