Dutch Cloisonne Tiles

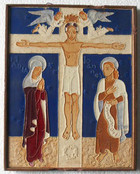

The 17th Century Golden Age of the Netherlands not only enriched sacred art with great works by Rembrandt but also with every-day craft objects on biblical themes: ceramic wall tiles. These double-fired clay plaques, glazed with tin oxide, show little of the technical skill of the Great Masters and were, mostly, copied from popular religious prints of the day by artisans, using cobalt blue or manganese purple paint. The sacred subjects on the tiles were often so obscure they required captions with Bible texts, but they found their way into humble farm houses and princely palaces in almost 600 different thematic variations (like the 19th century Crucifixion tile in manganese coloring in my collection.)

At the height of the fad, Dutch religious tiles were used to decorate fireplaces and became visual aids in teaching children the stories of the Bible. These hearth displays inspired one Methodist treatise in 1842, titled Dutch Tiles: Being Narratives of Holy Scripture; with Numerous Appropriate Engravings: For the use of Children and Young Persons. They also appear in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, published the following year, where they adorn the fireplace of Ebenezer Scrooge. By then, biblical tiles were already becoming antiques. Their Dutch makers had mostly gone out of business, faced with competition from mass-produced British and German tiles and a more insidious rival: cheap wall-paper.

Dutch biblical ceramics have great historical interest for me, but it was the chance discovery in an Amsterdam antique shop of a modern variation, which set me off on another Sacred Art Pilgrim quest. Alongside an assortment of traditional monochrome wall tiles, I found a multi-colored, glazed earthenware crucifix of contemporary design, where the image of Christ on the Cross was delineated by tiny raised lines in what is known as the cloisonné style, because of the resemblance to cloisonné enamel work, where colored areas of enamel are separated by strips of metal. This crucifix and similar tile-shaped plaques were not intended to be plastered into walls but hung on them as art pieces. In fact, the tiles usually come with frame-like borders.

Dutch cloisonné tiles were produced from around 1907 until 1977 in the Westraven factory in Utrecht and De Porceleyne Fles works in Delft, famed around the world for its blue-and-white ceramic ware. The process was labor intensive. Holes were pricked into a stencil sketch, and the image was transferred in powdered charcoal to a tiled-shaped gypsum mold. Grooves were, then, etched along the charcoal lines on the mold (made in one original and several working copies), corresponding to what would be the raised lines in the finished tile. A clay-like “cloisonné earth” mixture was spread over the talcum powdered mold to form the actual tile with its ridged surface. Next, crystal glazes in as many as 15 colors were squirted into the recessed areas formed by the raised lines. The ceramic pieces were, then, fired in a kiln.

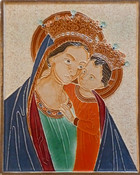

Religious subjects do not feature so prominently on cloisonné tiles of the modern era as they do on smooth-surfaced Dutch ceramics made before 1900. If didactic antique tiles with biblical inscriptions had appeal for Calvinist Protestants, the cloisonné tiles were designed for a more Roman Catholic market with their images of the Madonna and Child, the Passion of Christ, and the Saints. The notable exception in my collection is a commemorative tile made in 1948 for the First Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Amsterdam.

Tiles produced by De Porceleyne Fles have (to use a Dutch image) slightly higher “dike” walls, enclosing deeper areas of more variegated coloring than the pieces made by Westraven, as we can see in a comparison of tiles in the listings of Saint George the Dragon Slayer from the Delft and Utrecht workshops. In their simple but elegant imagery, both types of cloisonné tile are worthy successors to their ceramic prototypes of the Golden Age. Sad to say, they were also made obsolete by changing tastes and commercial market forces, but enough of them can still be found to delight contemporary sacred art collectors.