Cuban Graphic Art

Mention Cuban graphics to print collectors and the striking poster art of the Fidel Castro era immediately comes to mind. Even before the Cuban Revolution, the Caribbean island nation had a vibrant printmaking scene, turning out labels, logos, packaging, and posters for the tobacco, sugar, and tourist industries. Art trends in Cuba’s mighty neighbor, ninety miles to the North, heavily influenced local graphic design in the pre-Communist period, but the Cubans developed their own exuberant Art Deco style, drawing on the homegrown Vanguardia art movement, dating from the late 1920s, whose members had absorbed European modernism at the beginning of the century, while living abroad.

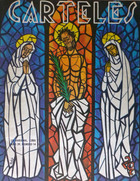

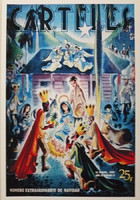

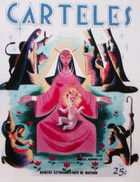

In this traditionally Roman Catholic country, religious images in the Cuban Art Deco style were made to order for publications like Carteles, a weekly compendium of news, sports, and lifestyle features, which was the second most widely-read magazine on the island before the Revolution. The cover image on a copy of the 1958 Easter issue of Carteles in the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection shows Christ, mocked, between two grieving women, in a stained glass design by noted magazine illustrator Andres Garcia Benitez. You can also see stylish Cuban Art Deco touches in his Head of Christ cover for the 1959 Carteles Easter edition and in the two whimsical Nativity scenes he created for the 1954 and 1956 Christmas issues of the magazine.

After Castro came to power in 1959, the commercial billboards and advertisements of Capitalist Cuba were replaced by murals and posters promoting the agenda of the new Communist state. From the mid 1960s until the breakup of the U.S.S.R. in 1991, a period viewed as the Golden Age of Cuban poster art, as many as 12,000 propaganda posters were produced on themes ranging from tobacco harvesting to solidarity with oppressed peoples around the globe. They were often closer in style to American Pop Art than the staid Socialist Realism of Chinese and Soviet poster art; mostly the work of graphic designers in three organizations: the Communist Party printing department (EP), the Organization in Solidarity with the People of Africa, Asia and Latin America (OSPAAL), and the Cuban Institute of Cinematic Art and Industry (ICAIC).

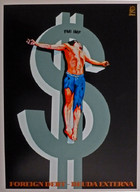

Religion was supposed to wither away in the new revolutionary society, but that did not prevent Cuban propaganda artists from creating their own Communist icons or appropriating useful Christian symbols. Photographer Alberto Korda’s Christ-like snapshot in March 1960 of Ernesto “Che” Guevara, titled, Heroic Guerrilla Fighter, has been artistically rendered in so many idealized variations that the bearded Marxist revolutionary in his black beret is now one of the most readily recognized (and, by some, revered) images in the world. Other sacred art references are more direct. To dramatize the plight of Developing World nations crippled by foreign debt, Graphic Designer Rafael Enriquez created a poster for OSPAAL in 1983, on display, here, in a reproduction, showing a figure in tattered pants, crucified on a dollar sign.

In what is, no doubt, the most controversial “borrowing” of sacred imagery in Cuban graphic art, a haloed Christ appears with an automatic rifle slung over his shoulder in a 1969 poster by OSPAAL Artist Alfredo Rostgaard, made in homage to Colombian Revolutionary Camilo Torres, a Roman Catholic priest who left the church in the 1960s to join the Marxist National Liberation Army (ELN). He was killed ambushing a Colombian government military patrol in 1966 and became a martyr for the Liberation Theology movement. In the image gallery, there is an original offset print of Rostgaard’s notorious Guerrilla Christ and a giclee reproduction of a later variation, titled, El Cristo de America, where the armed Jesus shows up again, framed by the flags of Latin American nations.

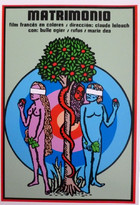

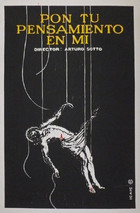

Until recent years, the most innovative center of official graphic art in Cuba was the ICAIC, where posters for Cuban and foreign films were made by the silkscreen method. ICAIC designers shunned traditional Hollywood-style posters for more symbolic interpretations of movie themes, sometimes using religious motifs, as can be seen in three pieces in the collection. The Cuban poster for French Director Claude Lelouch’s 1974 film, Mariage, shows the world’s first bickering couple in the Garden of Eden. A hand points toward a rosary in a minimalist black-and-white advertisement for La Ciudad Negra (A Town in Mourning), a 1972 historical drama by Hungarian Director Eva Zsurzs. The body of Christ dangles like a puppet with cut strings in a placard for Pon tu Pensamiento en Mi (Think of Me), Cuban Director Arturo Sotto’s 1995 film about an actor who is taken to be a new Messiah, when he performs apparent miracles on stage.

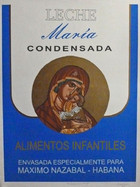

Sacred themes also appear in fine art prints in my collection by Contemporary Cuban Graphic Artists. Mercedes (Mercy) Rivadulla Perez, the daughter of famed movie poster designer, Eladio Rivadulla, portrays a Havana Christ making his triumphal entry all but unnoticed into a fantasical Cuban capital, where balloons fly and a woman reaches for the stars. In a silver-gelatin print, photographer Alberto Arcos creates a cross from images of sculpted drapery and disembodied limbs, while Miguel Angel Couret, a graphic artist from Pinar del Rio on Cuba’s Western tip, presents the Crucifixion in a metaphysical abstract. Icons of faith become marketing logos in Ruben Alpizar’s serigraph from his End of the Century Pamphlets series, where an image of the Madonna finds its way onto a condensed milk label.

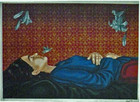

Multi-Media Artist Aimee Garcia Marrero also works with traditional religious signs and symbols to create pieces of ambigious meaning. Her untitled serigraph in my collection looks like a surrealist variation on a traditional Annunciation scene--a mysterious image of the moment of conception, featuring a portrait of the artist. The woman's hands rest on her womb. The humming bird hovering above her mouth is a messenger and bringer of life for the indigenous peoples of the Americas. The deep blue of the blouse is a color associated with the Virgin Mary; the white lilies, a symbol of her purity. Even the gold embossed cloth of the backdrop brings to mind the brocaded garments of angels in Annunciation paintings by the late medieval Flemish masters.

The most unusual Cuban graphic art pieces in the Collection are two handmade "books" from the beginning of the new millennium. The text of the poem, Jesus, by Cuban Poet Digdora Alonzo, contrasting the humanity and divinity of Christ, appears in script on a page extending accordion-like from a Christmas card with two reproductions of portrait drawings of Christ. A second collection of contemporary Cuban verse, featuring the title poem, Maps of the Prodigal Son by Jose Manuel Espino Ortega, has a truncated view of a map of the Holy Land on the cover, reproduced in full in a hand-colored fold-out page.

These handmade publications are the work of Ediciones Vigia (Watchtower Editions), a collective of writers and artists, which has been gathering since 1985 in the cultural center of Matanzas, 90 km. east of Havana, to handcraft books, magazines, leaflets, and scrolls in editions of no more than 200 out of scrap page and recycled materials. Working at long tables in a colonial-era mansion (partly subsidized by state funds), volunteers create each copy by cutting, pasting, coloring, and assembling mimeographed and photocopied images with text, often decorating them with yarn, aluminum foil, and whatever objects can be gleaned from the left-overs of Cuba's scarcity economy.

The economic aftershock from the breakup of the Soviet Empire hit Cuba hard, as it entered the twilight years of the Castro regime. The longterm future of the island’s once thriving propaganda art culture may be in doubt, but if Ediciones Vigia titles are any measure of future trends, sacred themes will continue to preoccupy Cuban artists, inspiring works that are sardonic, ambivalent, ambiguous, and, perhaps, hopeful, whatever graphic form they make take.

Information taken from Revolucion!: Cuban Poster Art by Lincoln Cushing (Chronicle Books, San Francisco: 2003)

Andres Garcia Benitez

Andres Garcia Benitez

Andres Garcia Benitez

Andres Garcia Benitez

Rafael Enriquez

Alfredo Rostgaard

Alfredo Rostgaard

Unknown Cuba Artist

Unknown Cuban Artist

Unknown Cuban Artist

Mercedes (Mercy) Rivadulla

Alberto Arcos

Miguel Angel Couret

Ruben Alpizar

Aimee Garcia Marrero

Jesus (Front and Back Cover)

Jesus (Inside view, Fold-out text)

Jesus (Inside view, Illustration)

Maps of the Prodigal Son (front cover)