Mexican Figurative Pottery

Pottery-making is by far the most popular folk art form in Mexico today with deep roots in the history and culture of this Central American nation. Archaeologists have found coarse pottery shards in Central Mexico, dating from as far back as 2300 B.C. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the early 16th century the Aztecs had perfected a form of black-on-orange ceramics of intricate geometric design, made from hand-coiled clay, fired at low heat. The European colonizers brought potter’s wheels, glazes, and closed kilns, and local artisans were soon able to produce glazed Talavera pottery, rivaling the Old World maiolica tin-glazed ceramics on which they were modeled. The current international craze for handcraft art has inspired even more variations in clay from Mexican potters, using methods both ancient and modern, associated with specific regions or family workshops.

Mexico has a particularly rich tradition of figurative pottery, beginning with the Olmec Civilization (1200 BC-400 BC), known for its “baby-face” ceramic figurines. The Mexican pottery pieces in the Sacred Art Pilgrim collection represent a contemporary form of ceramic-making, which developed when village artisans who normally made clayware items for everyday use realized there was a growing market for more decorative items among wealthy Mexicans and international folk art collectors. The most notable was American Multimillionaire Nelson Rockefeller, who bought his first Mexican ceramic pieces, while wandering through rural markets in the 1930s. At his death in 1979, Rockefeller had amassed close to 3,000 Latin American folk art objects, now housed in the San Antonio Museum of Art and the Mexican Museum in San Francisco. Among his last acquisitions were clay figures from the women potters of Oaxaca.

Mexican figurative pottery is made from clay, dug out during the dry season from soil layers often found three to five meters underground. It is pulverized and sifted into a fine powder; then, water is added and the mixture is trodden into a malleable material, which can be stored in plastic bags to last through the rainy season. Artisans making sculptural pieces cut the clay into slabs and roll or fold them into hollow cones to create the figure torso, leaving holes for the head and limbs. Details might be etched into the clay, using the sharp end of a maguey “century plant” thorn. The finished ceramic pieces are left to dry in the sun. Then, the “greenware” pottery is baked in an open pit wood fire or fired in a kiln to become terracotta. Some artisans paint or treat the clay in special ways before firing it; others add color afterwards. Variations in technique define styles.

Sacred motifs often appear in Mexican ceramic pieces, combining traditional Roman Catholic and folkloric imagery. Skeletons are a popular theme, associated with the Day of the Dead, a holiday celebrated during the Feasts of All Souls and All Saints, which incorporates pre-Hispanic religious rituals. Christ is mostly represented as a babe-in-arms in clay figure groupings. Among saints and angelic intercessors, the place of honor goes to Our Lady of Guadalupe, who appeared to the Aztec peasant, Juan Diego, in December 1531, leaving behind a sacred image, which has become a national emblem, depicted in a gleaming Talavara ceramic plaque from Juana Ponce. Arboles de la Vida (Trees of Life), traditionally depicting scenes from the Garden of Eden, are another favorite genre. They were once used as visual aids in explaining the origins of the universe to the non-Christian, indigenous peoples.

Trees of Life are a specialty of ceramic artists in Metepec, a municipality 50 km. west of Mexico City. Local potters embellish trunk-like clay forms with all manner of tiny, hand-molded angelic, human, and animal figures; birds and butterflies; flowers and leaves; as well as the heavenly bodies, attaching them to the stump with tiny wires. These finished clay arrangements are, then, fired in an oven and painted in rainbow colors. The collection includes a ceramic Tree of Life of the Creation story by Potter Juan Hernandez Arzaluz and his wife, Maribel, famous for their highly detailed, miniature pieces, and a Tree of Life of the Expulsion from Eden by Jaime Esquivel. There is also an unpainted terracota Tree of Life Nativity scene by Metepec ceramicist, Carlos Moises Soteno, the oldest of three artisan sons of Tiburcio Soteno, a master Tree of Life sculptor, who has expanded the genre’s thematic range to include secular, historical subjects.

Potter Gerardo Ortega and his family create Tree of Life candelabras and Tree of Life crosses using clay treated with “betus” pine resin oil to give it a brilliant sheen. Betus clay ceramics come from the central western state of Jalisco, where Ortega runs a multi-generational workshop in the pottery center of Tonala, turning out whimsical ceramic sculptures, melding religious and folklore motifs in a style he describes as “surrealism in mud.” One such figure grouping in the collection shows a winged woman, sheltering a disparate group of people under a huge yellow cloak, including a bespectacled nun; a vender carrying chickens on her head to market; and three bare-back bull riders. The scene recalls traditional Catholic imagery of the Virgin of Mercy, offering shelter to sinners under her all-encompassing mantle. The Holy Family on the Road depicts Mary, Joseph, and the Baby Jesus in a touring car with the Three Wise Men.

Another ceramic artisan from Tonala with four pieces in the collection is Moises Rodriguez. He creates “burnished” pottery, using a stone, often pyrite, to polish and smooth away any pores in the clay surface of his pieces, before painting on his designs in natural pigments, mixed in a clay-water slip. Burnished pottery is fired at low temperature, resulting in semi-sculptural works with a soft luster and muted colors. It is known as “scented clay,” because it preserves the freshness and flavor of liquids, when molded into pots, vials or jugs. Rodriguez uses a traditional Tonala style of “feathered” decoration in his two burnished pottery crucifixes and the pleat-edged plate, depicting the release of St. Peter from prison. Three Rodriguez pieces in my collection are holy water stoups with images of the Annunciation, Pieta, and the Holy Family, a copy of Michelangelo's famous Doni Tondo painting in the Uffizi gallery in Florence, Italy.

The impoverished, southwestern state of Oaxaca is known for its women potters, who took up ceramics to supplement their incomes, after their men folk headed north to find work in the U.S. The town of Ocotlan de Morelos is home to one of the best known Oaxacan matriarchal pottery dynasties: the Aguilar Sisters. Josefina, Guillerma, Irene, and Concepcion first learned their “magical realist” style of pottery making as children, working beside their mother, Isaura Alcantara, who was an early innovator in decorative ceramics. Josefina is the best known of the Aguilar Sisters. She not only creates her own delightful clay sculptures and figure groupings but oversees the work of about two dozen family members, who mold pieces in a similar style, which go out under her “brand name.” Her two sons, Demetrio and Juan Jose, have followed in their mother's footsteps and gained recognition in their own right for a more textured style of pottery.

The Aguilar family is represented in the collection by five pieces, three with the signature, “Josefina Aguilar,” and two by her sons. A detailed figure grouping by Josefina depicts the appearance of Our Lady of Guadalupe to Juan Diego. The Virgin stands, emblazoned with the sun, moon, and stars, atop a hillside, decorated with cacti, a maguey “century plant,” and a swimming swan, while a cherub with wings the color of the Mexican flag keeps watch at her feet. Josefina's market vendor with the Virgin headress belongs to her popular munecas (Spanish for “dolls”) series. A clay figure of St. Margaret stands triumphantly on the dragon that swallowed her whole.

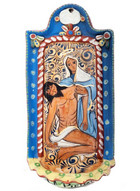

Son, Jose Juan, has created a charming statuette of Pope John Paul II, who visited Mexico on his first overseas pilgrimage in 1979 and made four more visits during his 26 year papacy. Our Lady of Guadalupe seems to be peeping out from his vestments. Josefina's second son, Demetrio, is represented here by a ceramic variation on traditional Catholic imagery of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, drawn from the Twelfth Chapter of Revelation, where a woman crowned in stars and clothed in the sun gives birth to a man child, who is threatened by a dragon and taken up to the Throne of God.

In Demetrio's detailed composition, the Baby Jesus looks as if he is being snatched up to heaven directly from his mother's womb. His billowing loin cloth suggest traditional images of the Resurrection. In a tiny figure grouping at the base of the sculpture, the crowned Madonna and Child wave triumphal paper banners decorated with mystical, Eucharistic motifs, as they watch the Archangel Michael deliver the coup de grace to the writhing seven-headed dragon of Revelation, a symbol of the triumph of good over evil at the End of Time.

Unknown Mexican Artist

Juana Ponce

Juan Hernandez Arzaluz

Jaime Esquivel

Carlos Moises Soteno

Gerardo Ortega & family

Gerardo Ortega & Family

Gerardo Ortega & family

Gerardo Ortega & Family

Moises Rodriguez

Moises Rodriguez

Moises Rodriguez

Moises Rodriguez

Moises Rodriguez

Moises Rodriguez

Josefina Aguilar

Josefina Aguilar

Josefina Aguilar

Juan Jose Garcia Aguilar