Salvadoran Wood Paintings

La Palma is a town transformed by art. Visitors to this community of 24,000 in the mountainous north of the Central American nation of El Salvador marvel at the brilliantly colored wall murals decorating homes, hotels, restaurants, and shop fronts along its winding streets. There are stylized vistas of villages with variegated tile roofs, gaudily-plumed mythical birds, even psychedelic armadillos-- looking half like Picasso paintings, half like Mayan pictographs. This “La Palma Style,” reproduced on countless painted wood folk art objects, has come to represent Salvadoran contemporary art to the outside world.

The transformation of this coffee-growing, agricultural community into a leading folk art center dates from 1973, when Fernando Llort, a San Salvadoran student of architecture, theology, and art (with a passion for rock music and “hippie” culture!) settled in La Palma, where he had come on vacation as a child. As the story goes, he was watching a village boy rubbing the brown covering off a copinol tree seed to expose the white layer underneath and decided it would be an ideal surface for miniature folk art paintings. So, La Semilla de Dios (The Seed of God)—as Llort’s original folk art workshop was called—came into being.

LLort created La Palma’s trademark mythic-Mesoamerican, modernist look and passed it on to local artisans. Aminta de Mancia, founder of Grupo Artesanal Madero de Jesus (Woodworkers of Jesus) and Maria Estela Perlera de Portillo, whose works can be viewed in the image gallery, both mastered the Llort style, before launching their own workshops. They were not alone. Three years after La Semilla de Dios was legally incorporated as a folk art cooperative in 1977, fourteen more had appeared in La Palma. The number has now grown to over 80, employing 70% of the local population.

La Palma’s fairy-tale success story belies a grim historical reality. The community was a stronghold of rebel leaders from the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) during the Salvadoran Civil War (1979-1992), and pitched gun battles between army and guerrilla forces on village streets threatened the economic hopes and very lives of local artisans. The main church of La Palma was the setting for the first peace talks between then President, Jose Napoleon Duarte, and FMLN leaders on October 15, 1984, earning the town the epithet: Cradle of Peace.

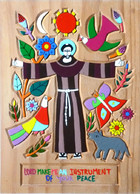

Images of Angels, Noah’s Ark, the Madonna and Child, the Nativity, the Last Supper, and other biblical motifs are popular subjects for wooden cut-outs, plaques, and folding triptychs from the artisan workshops of La Palma. One key variation on traditional sacred imagery stands out from all the rest. Remembering their community’s near miraculous return from the brink of destruction, La Palma folk artists depict the Cross not so much as an emblem of Christ’s death but as a celebration of peace, reconciliation, and the return to life—a theme beautifully expressed in the New Creation Cross from the Woodworkers of Jesus.

Unknown La Palma Workshop

El Roble Workshop

Madero de Jesus Workshop

Unknown La Palma Workshop

Unknown La Palma Workshop

Unknown La Palma Workshop

Maria Estela Perlera de Portillo

Unknown La Palma Workshop

La Semilla de Dios Workshop

La Semilla de Dios Workshop

La Semilla de Dios Workshop

15 de Octubre Workshop

La Semilla de Dios Workshop

Maria Estela Perlera de Portillo

Madero de Jesus Workshop