Andean Arpilleras

Arpillera is the Spanish word for “burlap.” You might well wonder what this humble, coarse fibered fabric has to do with the elaborately embroidered, story-telling panels in cloth of many colors that bear its name. The first arpilleras were actually embroidered feed sacks, which Chilean farm families produced for tourist markets. The burlap bag still remains the material of choice to provide backing for these exotic textile art pieces from the Andean region of South America, stitched together with bits of fabric and braid, yarn figures, and the occasional found object.

Nowadays, arpilleras mostly present bucolic scenes where peasant till fields and gather for village fiestas, but they once had darker stories to tell. After Chile’s Marxist President Salvador Allende was overthrown in a right-wing military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet in 1973, the families of those imprisoned, killed, and “missing” banded together in sewing circles supported and protected by the Roman Catholic Church to make arpilleras, whose sale not only brought in much needed income but conveyed images of what was going on in Chile to the outside world.

These stitched scenes of protest, no bigger than placemats in size, showed women and children waiting in food lines, carrying banners in demonstrations, as well as more explicit images of police crackdowns and torture. At first, the conservative dictatorship dismissed these needlework symbols of dissent as “women’s work,” but when the arpilleras began to attract attention abroad, they were denounced in the state-controlled press as “tapestries of defamation.” Police kept a close watch on the dissident sewing circles, harassed their members, and seized and destroyed arpilleras as subversive contraband.

Arpillera-making moved across the border into Peru in the 1980s, when Maoist Shining Path guerrillas drove peasants out of their homes in the Andean highlands and into crowded shantytown settlements surrounding the capital of Lima. Once again, communal sewing circles helped the poor and displaced to survive. A folded note from an unknown artisan in a pocket on the back of an embroided cloth panel in the Collection describes its image from the New Testament along with the date and the number of one such group of arpillera-makers in the Peruvian capital: This painting represents a biblical scene that is the miracle of Jesus, when he calmed the stormy sea and saved the twelve apostles from shipwreck. Group 4 Lima 7-9-90.

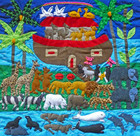

For the arpillera embroiderers of Peru, pastoral scenes with stunning mountain vistas, like the ones found in the Collection, were poignant recreations--amid urban squalor--of the rural way of life they had lost. Two biblical themes have proved especially popular with Andean arpillera sewers: Noah’s Ark and the Christmas story. Peruvian Textile Artist Balvina Huaytalla was only four when her family fled terrorist violence in the Ayacucho region. She learned arpillera embroidery in a Lima shantytown workshop and sees her art as “a way of sharing what I left in Ayacucho, the lovely land where I was born.” She sets her Nativity scene in my collection on the shores of Lake Titicaca, where visitors ride llamas to the Manger and reed boaters look up at a shooting Christmas star.

Fellow Refugee Leonor Quispe, represented here by a delightful cloth panel of Noah’s Ark teeming with pairs of applique animals, also believes “necessity forced her to be creative.” She tries with each piece of fabric she adds to her arpilleras to “bring my memories of Ayacucho to life.” In Quispe’s version of the Christmas story, the Three Wise Men make their way to the Christ Child in the foothills of the Andes, passing through flowering fields where cattle and sheep safely graze in a verdant landscape of memory.

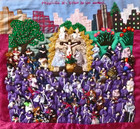

Two arpilleras in my collection by unknown Peruvian textile artists depict the Procession of the Lord of Miracles, when hundreds of thousands of the faithful join in carrying a much-venerated Crucifixion scene through downtown Lima every October in the largest religious gathering of this kind in South America. Countless miracles have been attributed to the original 17th century wall painting, believed to be the work of an African slave. Both embroidered images show pilgrims wearing traditional purple robes paying reverence to the Crucified Christ. The appliqued figures on the larger cloth panel with a view of the Lima skyline number close to one hundred!