Amate Paper Art

Amate tree bark paper is the papyrus of the Americas. “Amate” comes from the Aztec (Nahuatl) word for “paper." At the height of the Aztec Empire in the 16th century, close to half a million sheets were produced each year for use in the codices of royal scribes and priests, in sacred rituals, and as tribute payments. The Spanish Conquistadors banned amate paper because of its use in indigenous religious rites, but it continued to be made in remote regions of present day Mexico beyond the reach of the European invaders.

Ethnographers in the modern era revived interest in amate paper-making. By then, its production was largely limited to San Pablito, a village in the mountains of the east-central Mexican state of Puebla, where shamans of the Otomi people had preserved the ancient ways of making amate talismans. When the tourist industry took off in Mexico in the 1950s, Otomi artisans “secularized” their craft, creating tree bark paper cut-outs for the growing folk art trade.

Amate paper painting came about through cross-cultural cooperation between the Otomi paper-makers of Puebla and pottery painters from among the Nahua peoples, living in the Pacific coast state of Guerrero. In the early 1960s, Nahua potters painters decided to transfer their colorful designs from breakable clay ware to the easily transportable tree bark paper sheets used by the Otomi artisans they had encountered in Mexico City’s craft markets. A new folk art genre was born with roots in the manuscript art of the Aztecs.

The amate paper painters of Guerrero continue to be the largest buyers of bark paper from San Pablito, where artisans follow a paper-making recipe little-changed since Aztec times. Bark and fiber strips from wild fig trees, nettles, or mulberry bushes are boiled with ash and lime. The softened shreds are, then, arranged in crosshatch patterns on wooden boards and fused together by pounding with flat volcanic stones. The surface of the sheets is smoothed with the oily side of orange peels and left to dry in the sun.

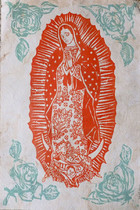

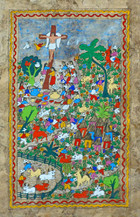

The first amate paintings from Guerrero replicated the floral and bird patterns of traditional Nahua ceramics. Artisans soon expanded their visual repertoire to include multi-level landscapes in flat perspective like the painting by Tomas Ramirez in my collection showing a village wedding. Sacred subjects range from portraits of the Virgin of Guadalupe and simple scenes of rural Marian shrines to panoramas of country life where the Nativity or the Crucifixion appears as one of many visual vignettes in busy compositions.

Amate artisans mostly reproduce images in copy-book fashion with variations typical of the villages where they live. Felix Venencio from Ameyaltepec has created a rural scene in my collection on the theme of work and prayer quite different from the usual 60 x 40 cm. format amate paintings. We see campesinos laboring in the fields and tending cattle in corrals in nine interconnected rows on a long, narrow amate sheet. The tenth and final tier shows two kneeling figures with rosaries in hand beside a verdant cross.

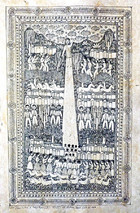

One of the best amate paper artists worked primarily in pen and ink. Cristino Flores Medina and a neighbor from his home village of Ameyaltepec were making folk art pieces in a Mexico City gallery, when the idea of transferring painted images from ceramics to paper was first discussed. They introduced the innovation to the artisans of Guerrero. Flores Medina eventually switched from painting colorful landscapes to drawing detailed narrative pieces in pen and ink like his beatifully balanced depiction of the Ascension of Jesus in the Collection, where Christ rises to heaven on a beam of light, blessing both humans and beasts ranged in rows below in a typical Mexican landscape.

Flores Medina’s depiction of the Last Supper in my listings follows a more complex narrative plan, where actions unfolding over time occupy the same visual space. On the lower level, Jesus shares the Last Supper with his disciples; in the middle, he prays in the Garden of Gethsemane, while they sleep; and in the upper half of the panel, the temple guard come to arrest Christ against the backdrop of a sleeping village in a starry night. There is nothing random in this beautiful arrangement of visual moments of sacred history.