Puerto Rican Serigraphs

Puerto Rican serigraphs are the offspring of a fortunate and fruitful union of politics and art. The years after World War II were a time of increased economic growth, urbanization, and social change in the U.S.-controlled Caribbean island. Under the enlightened leadership of Luis Munoz Marin, then, President of the Senate, Puerto Rican officials enlisted local art-makers to create films, plays, books, pamphlets, and posters promoting education, culture, and modernization among the island’s rural population, living in impoverished barrios without access to the mass media.

The communal information initiative was inspired by New Deal programs of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt like the Federal Art Project, which found artists public works jobs during the Depression. Two key players in the Puerto Rican campaign were, in fact, New Deal “liberals” from the mainland, Jack Delano (1914-1997), a photographer and composer, and his artist wife, Irene (1919-1982), who organized the first print-making section of the Workshop of Cinema and Graphic Arts of Public Parks and Recreation, launched by Senate President Marin in 1946.

When Marin became the first democratically elected governor of Puerto Rico in 1949, he drafted a law, merging the Workshop into the more ambitious Community Education Division (DIVEDCO) of the Department of Education. DIVEDCO became synonymous with a progressive style of Puerto Rican public art, influenced in part by New Deal art projects, the Mexican muralists, the avant-garde art of Soviet Russia, and Italian postwar Neorealist cinema. It is sometimes referred to as “Puerto Rican Bauhaus” for its resemblance to this interwar German Modernist arts and crafts movement.

The poster was DIVEDCO’s primary propaganda tool in the visual arts, and from the very beginning, serigraph printing was the favored medium. Serigraphs are made by pressing ink or paint with a special tool through a stenciled mesh screen, traditionally made of silk, to leave an imprint on a sheet of paper. It is a cost-effective reproduction method, requiring no expensive printing presses or photo-copying equipment. Since each print is made by hand, the final images can be considered original works of art.

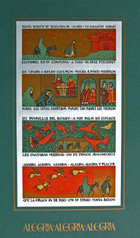

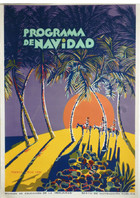

Irene Delano promoted serigraph posters as head of DIVEDCO’s first print workshop. Her command of the medium and attention to typography are evident in the collection print, Alegria, Alegria, Alegria, recounting the Holy Family’s journey to Bethlehem. Delgano also developed a line of Christmas cards where medieval Spanish and Moorish imagery of the Three Kings replaced mainland Santas and reindeer. The Delanos were honored in a 1981 retrospective art show, whose poster by Eduardo Vera Cortes (1926-2006) reproduces Irene’s distinctive card designs.

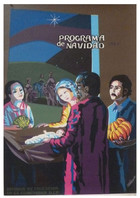

Traditional religious subjects feature in DIVEDCO posters advertising community Christmas events. Jose Melendez Contreras (1921-1988) uses imaginative typeface and contrasting colors in a 1966 holiday program poster of the Christ Child in the Manger and illustrates the Story of Salvation from the babe in swaddling clothes of Christmas to the Resurrected Christ of Easter in a 1960 print offering season’s greetings. The Wise Men worship the Light of the World in a print by Isabel Bernel, the best known Puerto Rican woman artist in DIVEDCO, advertising Camuy municipality holiday festivities,

Puerto Rican holiday serigraphs extol the joys of a traditional countryside Christmas. A trinity of doves descends from Heaven and the Bethlehem star shines over both San Juan’s citadel and rural wood-frame jibaro houses in a 1983 Eduardo Vera Cortes holiday serigraph. A DIVEDCO poster by Antonio Maldonado (1920-2006), depicts a column of parranderos (carolers) with instruments in hand, wending their way to the next rural dwelling to gather more neighbors for their Christmas Eve songfest.

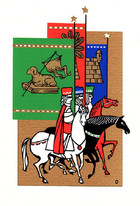

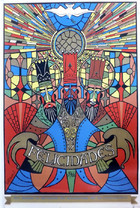

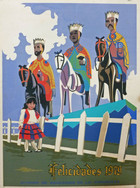

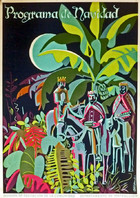

The Three Kings predominate in sacred-themed seasonal serigraphs, since gifts are traditionally given in Puerto Rico on January 6th, El Dia des Reyes (The Day of the Kings), celebrating the visit of the Magi to the Christ Child. The trio make a dazzling appearance in a psychedelic vision in stained glass on a 1966 DIVEDCO poster from Vera Cortes and appear as huge figures on a parade float in a 1979 serigraph from Bernal. Luis Manuel Rodriquez shows a boy and girl on the eve of the holiday gathering grass for the Wise Men’s horses in a shoebox they hope will be filled with gifts from these visitors who slip into their homes, small and unseen, while they sleep.

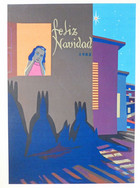

In three DIVEDCO serigraphs from the prolific Maldonado, the well-travelled Wise Men (who always come on horseback) cross a tropical strand under a blazing sun and make their way through a lush rain forest to take part in a contemporary manager scene where villagers bring bananas and a melon to the Holy Family. In a fourth print, the gift-bearers cast long shadows on a city street, where a young girl anxiously waits at her window.

The Magi appear as carved wood figurines, known as santos, in the oldest serigraph in the collection, a 1953 holiday poster by Lorenzo Homar (1913-2004) who had replaced Delano the previous year as head of the DIVEDCO print workshop and initiated a public-funded graphic arts group in 1957 at the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture.

The Wise Men as folk art sculptures also feature in a serigraph advertising a 1979 exhibition at San Juan’s Sacred Heart University; in a manger scene by Saint-Maker Carlos Anzueta in a 1984 season's greetings poster from Bernal; and in a 1989 commemorative poster from Lyzette Rosado, marking the 30th anniversary of the the National Crafts Fair of Barranquitas, a town in the mountainous center of Puerto Rico that hosts the oldest folk art festival on the island.

Rafael Tufino (1922-2008), one of the most popular DIVEDCO print-makers, brings together Puerto Rican seasonal “iconography” in a 1974 Christmas program poster, where we see the galloping Three Kings, a guitar playing parrandero in his traditional pava straw hat, and an assortment of festive instruments, including a hollowed-gourd guiro percussion piece. There is also a wood carving of the Archangel Michael with his scales of justice, the patronal saint of the celebrating community, whose coat of arms is just visible to the right.

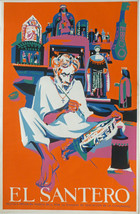

One major goal of the state-sponsored information program was to instill pride in traditional Puerto Rican arts and crafts. A venerable santero (saint-maker) puts the finishing touches on a religious wood carving in another Tufino poster, promoting the 1956 DIVEDCO dramatized documentary, El Santero, profiling the devout wood carver, Zoilo Cajigas, who cannot sell his handmade santos in a religious art market crowded with mass-produced plaster saints. He finds they are more valued as folk art pieces at the Museum of Anthropology, History, and Art, the first to open on the island in 1951.

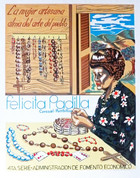

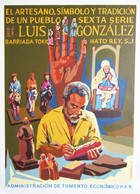

The Puerto Rican Administracion de Fomento Economico (Economic Development Administration) also commissioned serigraphs from noted print-makers celebrating Puerto Rican folk art. A 1981 poster from Jose Luis Gonzalez de Rosabel shows Felicita Padilla from the town of Corozal crafting rosary beads, praising her as "the woman artisan--the soul of village art." A hand with holy finger puppets looms large behind Luiz Gonzalez as he shapes a saintly figurine in his workshop displaying images of the Wise Men and the Virgin Mary in a 1983 serigraph from Maldonado, where the wood carver is described as "the artisan--symbol and tradition of a people."

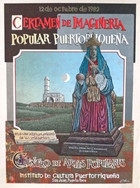

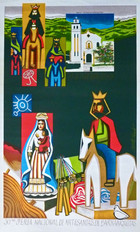

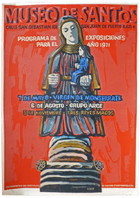

Serigraph posters often feature images of the Virgin of Monserrat, one of the most popular themes of Puerto Rican saint-makers, who appeared in 1599 to a landowner threatened by a bull in the Western Puerto Rican town of Hormigueros, now the site of a pilgrimage shrine. Master Printmaker Homar features a carving of the Monserrat Madonna by Early 20th Century Saint-Maker Pedro Arce in a 1971 poster with the exhibition program for San Juan's Santos Museum, sponsored by the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture. Sixto Cotto (1955-2015), representing a younger generation of serigraph artists, presents another santos of the the Virgin against the backdrop of the Hormigueros basilica in a print promoting a 1982 popular arts competition of the Culture Institute.

As television antennae sprouted up across the island, there was no longer a need for public print workshops turning out informational posters. Government funding dried up. The Institute of Puerto Rican Culture closed its graphic arts section in 1986; DIVEDCO shut down three years later. By then, numerous independent taller workshops had appeared across the island, established by artists who learned their craft from the Generation of the 1950s that had been formed and fostered by these experimental, state-sponsored, poster-making programs. What began as propaganda had evolved into fine art.

Jack Delano

Irene Delano

Irene Delano

Irene Delano

Irene Delano

Eduard Vera Cortes

Jose Melendez Contreras

Jose Melendez Contreras

Isabel Bernal

Eduardo Vera Cortes

Antonio Maldonado

Eduardo Vera Cortes

Isabel Bernal

Luis Manuel Rodriguez

Antonio Maldonado

Antonio Maldonado

Antonio Maldonado

Antonio Maldonado

Lorenzo Homar

Maruchi

Isabel Bernal

Lyzette Rosado

Rafael Tufino

Rafael Tufino

Jose Luis Gonzalez de Rosabel

Antonio Maldonado

Lorenzo Homar